MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. Eleanor Roosevelt article quoted from “Memorandums from Mary” website. Dr. Seuss cartoons from the UC San Diego Digital Library collection. Peanuts panel and Charlie Brown copyright Peanuts Worldwide LLC, All Rights Reserved. Captain America copyright Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Worldwide Inc., a division of The Walt Disney Company. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators and license holders, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

And this is the point in the saga where comic books themselves became criminal. Well, criminalizing.

The events unfold like a procedural and are supported by well-established historical evidence. Only the occasional snarky opinion has been added to protect the reader’s entertainment value.

The House Un-American Activities Commission began in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty and rebel activities on the part of private citizens, public employees and organizations suspected of having Communist ties. Citizens suspected of such would be tried in a court of law. But within a year, HUAC investigations would include pro-fascist, domestic Nazi affiliates.

There’d certainly been early warning signs, in addition to all those militias. In October 1938, for instance, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dubuque, Iowa made national headlines attacking swing jazz as “a degenerate musical system destined to gnaw away at the moral fiber of young people” and led down “the primrose path to Hell.” This denouncement followed on the heels of the music being banned in Germany due to its African and Jewish origins.

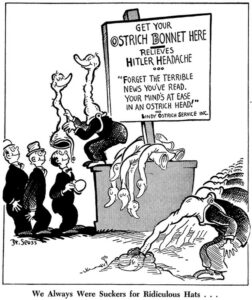

By Eleanor Roosevelt’s Winter 1939 article “Keepers of Democracy” in the Virginia Quarterly Review, the First Lady would describe some US citizens as having allowed themselves “to be fed on propaganda which has created a fear complex…People have reached a point where anything that will save them from Communism is a godsend, and if Fascism or Nazism promises more security than our own Democracy, we may even turn to them.”

And indeed, anti-democratic, racist messaging had infiltrated deep into Depression-torn America. In June, HUAC’s witnesses included the 5- hour testimony of US Army Gen. George Van Horn Moseley, who railed that a “Jewish Communist conspiracy” was seeking to control the US government, President Franklin Roosevelt was attempting to create a dictatorship, and immigrants and refugees fleeing Nazi oppression should be sterilized. The general’s testimony was supported by Donald Shea of the American Gentile League, whose statements were deleted from the public records by HUAC as too objectionable.

Below: Madison Square Garden, February 20, 1939. The “Pro-American Rally”, a US Nazi, anti-communist event with over twenty thousand attendees.

While still ever-watchful of communists, several pro-authoritarian organizations were exposed by HUAC and, despite J. Edgar Hoover’s personal politics and side-hustles, investigated by the FBI. In 1940, following a long fight with HUAC (and its predecessor, the Dies Committee), even the Silver Legion’s William Dudley Pelley took a hit. Found guilty in North Carolina of financial fraud, his headquarters were raided and his property seized. As it had done with the Depression, FDR’s New Deal was slowly turning back a rising fascist tide within the US.

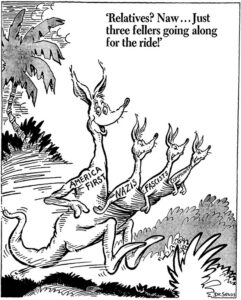

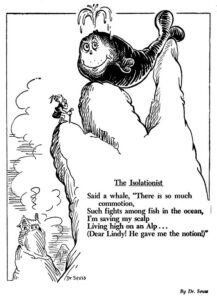

But some prominent right-wing groups still fought to capture public opinion and influence the national discourse, especially around the growing war in Europe. One, the America First Committee, formed in 1940 by Yale law students including future president Gerald Ford, future Peace Corps director Sargent Shriver and future Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, was expressly isolationist and pro-fascist, supported by NAM corporations, evangelicals, Catholics and included aviation hero Charles Lindbergh as a spokesman.

Yet anxiety over foreign affairs wasn’t quite enough. What conservatives really needed to imprint their brand of politics upon the average frustrated citizen was a new cause celebre. A fresh boogeyman, something more homegrown. They soon found the perfect subject: Americans were now consuming comic books, with millions of copies of the new medium selling monthly.

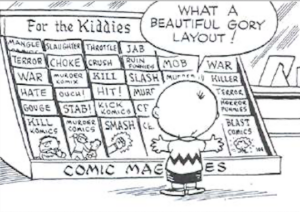

The first shot came from Sterling North, Chicago Daily News literary editor, Wisconsin-born Methodist and future author of the bestselling novel Rascal (which featured sincere, rustic family values and a lovable raccoon). Publishing an editorial on May 8, 1940 entitled “A National Disgrace,” he concluded comic books were “a poisonous mushroom growth of the last two years” and its publishers were “guilty of a cultural slaughter of the innocents.” He questioned the Low Culture and amorality American children were exposed to in comic books, proclaiming them “Badly drawn, badly written and badly printed -a strain on young eyes and young nervous systems…Their crude blacks and reds spoil the child’s natural sense of color; their hypodermic injection of sex and murder make the child impatient with better, though quieter, stories.”

Conservative groups quickly began stoking concern over the impact of a cheap, disposable, vulgar entertainment’s effect on America’s youth. Big money going to salacious New York (i.e.: Jewish, non-Christian) publishers, rumored to be pornographers and mob-affiliates? Who trafficked in amoral, violent picture-stories available to kids? This could not stand! Think of the children! Soon, pulpits and PTAs started complaining. And with traditional prejudices well sublimated, a new national debate began.

By early 1941, Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz were feeling the heat. Wanting to avoid any close public scrutiny into their business dealings, or threats to their cash cow Superman, they played things safe. They publicly announced DC-National had formed an editorial board to review its comics, with the board members’ names and expert credentials prominently displayed inside DC’s books, in hopes of warding off accusations that their product was unhealthy for children.

One result of this new policy would be DC partner Max Gaines accepting a proposal in 1941 from noted psychologist (and developer of the lie-detector machine used in law enforcement) Dr. William Moulton Marston for a “healthy, positive role-model for young women,” the female superheroine he called Wonder Woman. Marston would also later provide an article defending the medium (“Why 100,000,000 Americans Read Comics”) to the journal The American Scholar in 1943.

Other publishers quickly made similar assurances of their good intentions, proudly showing off their paid-for, positive endorsements from celebrities, psychiatrists and the like. For leaders in the lucrative comics industry, these were affordable concessions. And for a while, critics and the general public were satisfied. Besides, there were other worries. Like looming war overseas.

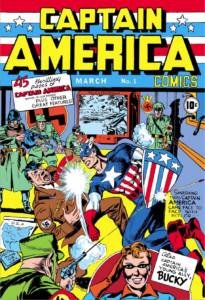

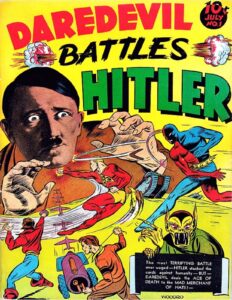

You see, the industry, meanwhile, had proudly started expressing its politics, supported by direct requests from the federal government. FDR himself was appearing in stories congratulating characters for defending their country from spies and saboteurs. And in March 1941 (cover date; it actually hit the stands December 1940), Simon & Kirby’s Captain America showed Cap punching Hitler on the cover of its debut issue. Lev Gleason dropped Daredevil Battles Hitler #1 that July. Anti-fascism, coupled with patriotism, began creeping into comic books, and never really left.

Then came Pearl Harbor. Following the December surprise attack and the US entering the war, the CIO pledged to aid America in its defense efforts and suspend union workers strikes for the duration. NAM members took no such vow however, and several (DuPont, Standard Oil and United Steel, for instance) continued selling to overseas enemies, even as their free-market, anti-union associates like America First faced criticism over questionable politics.

Having disbanded his Silver Legion militia, true-believer William Dudley Pelley, on the run and ducking federal subpoenas, still kept up public attacks against the government and FDR. A free-market isolationist and religious zealot preaching skin pigmentation as a visible marker of spiritual worth (with “negroids” at the bottom and Caucasians at the top, of course), Pelley continued organizing, publishing, and speaking engagements. Declaring Japan’s attack was deliberately instigated by Roosevelt to involve the US in global war and seeing America as undermined by a “Jewish contamination of Christianity,” as well as Communists and subversives, he publicly called for all Jews to be ghettoized. Arrested and found guilty on 11 counts of sedition and treason, including obstructing military recruitment during wartime and aiding the German war effort, he was jailed by 1942, sentenced 15 years, serving eight.

Such movements would be considered unpatriotic, and pro-fascism would be marginalized in the United States…temporarily. Former members of the Silver Legion would be heard from again.

Countering such setbacks in “faith-based” governance, the militant and fundamentalist “National Association of Evangelicals for United Action” formed in Sept. 1941, soon expanding membership but shortening its name to the softer National Association of Evangelicals [NAE] in April 1942.

Promoting a (predominantly white) fundamentalist culture of conservative “traditional Christian values”, it developed global chains of missionary networks, syndicated radio shows, publishers, music, movies and bookstores (including distribution of evangelical comic books and, in time, “new translations” of the Bible aligned to their doctrines). It also linked nearly 40 different denominations of 45,000 local churches representing millions with the desire to influence their money, votes and beliefs upon congress, the courts and, ultimately, the White House.

Anglo-Israelism gospel had finally found a solid home base, financing and a political lobby in the USA.

That same year, Crime Does Not Pay debuted to become a salacious, public hit, and Americans would purchase more than a billion comic books, including a full 25% of all reading material shipped to American troops overseas. Worries over the comic book medium went on the back-burner, due in part to their use in the military as teaching tools and their effective impact as propaganda supporting the war effort. And as simple, disposable entertainment, they also made great morale boosters.

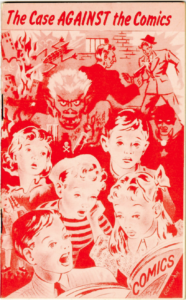

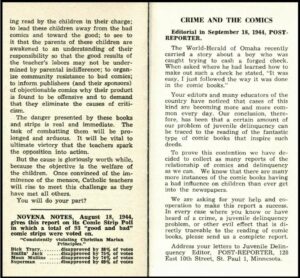

But moral seeds had been planted, and concerns over comic book violence would remain. They’d blossom during wartime and into the post-war era, tapping into national anxieties, nurtured by populist debates in radio shows, newspapers and magazine articles (“Are the Comics Harmful Reading for Children?” by Milton Caniff, Coronet magazine, Aug.1944). Nurtured also by conservative regional civic groups like the PTA, American Legion, Chambers of Commerce, various Southern Methodist, Baptist and other NAE churches…and, finding its patriotism after a Nazi armed blockade of the Vatican, soon on-boarding the Catholic Legion of Decency (“Comics” by Sister Mary Clare, 1943; “The Case Against Comics” by the Catechetical Guild, 1944 and others).

With an eye on taking back Congress from New Deal Democrats after the war, the Right began focusing again on a platform of “anti-communism” and “traditional Christian-American values.” These values included opposing segregation, especially in the military. And in some sectors, it need hardly be said, suspicion of Jews. Especially industries considered Jewish-controlled, like those amoral movies and comic books.

And to combat this, they’d bring their own experts.

To Be Continued…