MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. Complete Mystery and all related materials are copyright Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Worldwide Inc., a division of The Walt Disney Company. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators and license holders, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

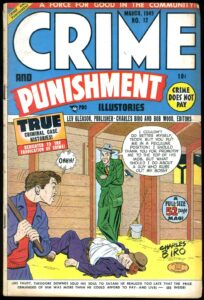

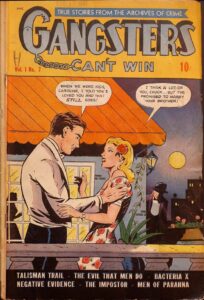

In 1948, Lev Gleason, bestselling publisher of Crime Does Not Pay, Crime and Punishment, Daredevil Comics and a leftist Democrat, could see where all the rabble-rousing was headed. He organized an industry-wide body he called the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers [ACMP] to avoid external regulation. It banned depictions of sympathetic criminals, scenes of sadistic torture, the humorous or glamorous depictions of divorce, foul language, and ridicule or attack on religious or racial groups.

Joined by a few companies, he was rebuffed by most major publishers. DC-National had their own hired professionals to endorse their product, thanks; Dell-Western, citing their Disney licensing, newspaper strip IP and children’s titles, publicly claimed they published only wholesome family entertainment, not like those other publishers, and were exempt. And so on.

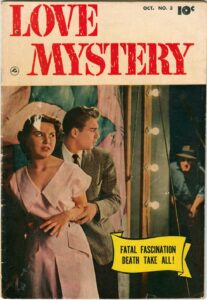

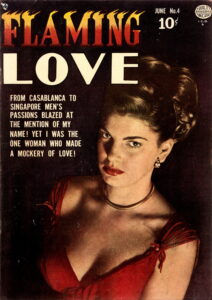

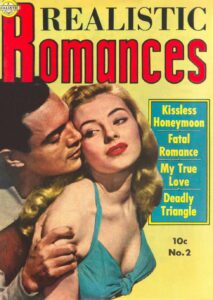

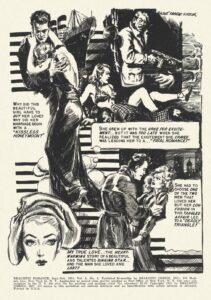

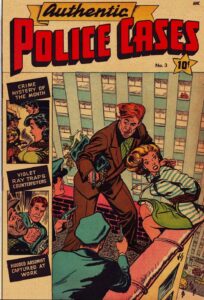

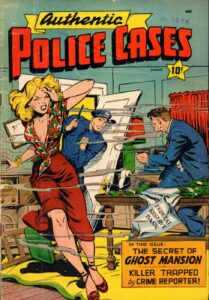

Surveys from the post-war era showed that well over half the youngsters in the USA were regular readers of comic books. Through the 1940s and ‘50s, some found at least four out of every five kids were familiar with them, albeit often on a pass around basis. Sales over the 1948-51 period alone reached 14%, 12%, 10% and 13% of the overall market, not including overseas sales. Market assessments for just the new genre of romance comics (not including teen comics) began with one percent market share in 1947, then leaped to 23% and 27%, respectively, in 1949 and 1950. From 1948-50, roughly one comic in seven was a crime title, and even women’s comic book titles included mystery, crime and dark suspense tales mixed with the romantic melodrama, such as in Love Mystery, Flaming Love, Strange Confessions and others. (By 1951, Realistic Romances even featured another unauthorized adaption of the noir film Gun Crazy. Although swapping the lead roles, it followed the movie plot right down to the conclusion’s fatal showdown in a swamp.)

Though Lev Gleason’s ideas were noble, profits remained too solid to risk and no one was realistically going to budge. Crime was big. Comics were big. Crime, mystery and thrills sold comics. Even if parents were concerned about America’s youth having access to them, nothing was going to change unless market forces or legislation dictated their doing so. Lacking any uniform participation or standards of review, the ACMP remained toothless. Every company would be on its own.

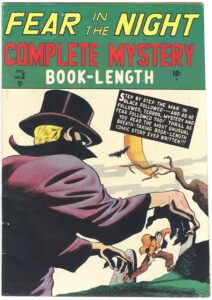

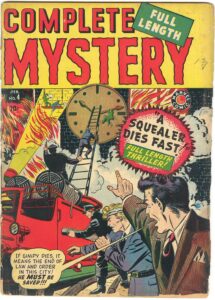

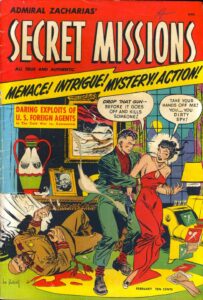

Some publishers could afford ignoring the pressure, but most couldn’t. The Timely-Atlas-Marvel group, for instance, was a long-time pulp and girlie magazine outfit who made its comics income from derivative and slightly lower-tier crime, mystery, romance, westerns and teen humor, plus a few struggling superhero titles left over from the war. Feeling the squeeze, its editor-in-chief Stan Lee, still fresh from military service and brash as only someone related to the publisher’s wife could be, pushed back against Dr. Wertham and the campaigns, even as his editorials also cautiously cited the company’s own experts.

And while we tend to think of the anti-comics crusades as a uniquely American phenomenon, conservative political censorship, supported by global religious networking, was also brewing overseas in post-war Europe. Dutch Minister of Education Theo Rutten of the Catholic People’s Party published a letter in the October 25, 1948 issue of the newspaper Het Parool directly addressing educational institutions and local government bodies, advocating the prohibition of comics.

“These booklets, which contain a series of illustrations with accompanying text, are generally sensational in character, without any other value,” he stated. “It is not possible to act against the printers, publishers or distributors of these novels, nor can anything be achieved by not making paper available to them, as the necessary paper is available on the free market.”

Censorship followed. Exceptions were made for the “healthy” comic productions from the Toonder studio, who made the Netherland’s much-beloved Tom Poes (“Tom Puss”), a cartoon strip about a clever white cat and his pal, a dim brown bear.

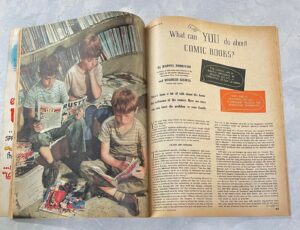

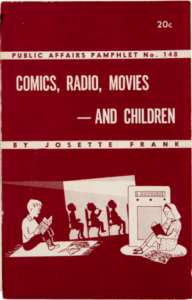

Back in America, as conservative messaging won more elections by 1949, media pressure and public protest grew: Commentary magazine ran an article claiming comic books were lessons in fascism (“Comic Books and Other Horrors”; Jan.), echoed by Family Circle (Feb.: “What Can YOU do about Comic Books?”), the Public Affairs Pamphlet Series #148 (“Comics, Radio, Movies—and Children” by Josette Frank; Mar.), Household magazine (“The Truth About Comics” by Josette Frank again; Mar.) and the journal Sociology and Social Research (“Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency”; Mar.-Apr.).

Then in March the New York State Legislature established a Joint Committee, charging it with making “a thorough study and survey” of comic books, including the extent they offended “accepted standards and the public interest [and] the dangers and evils” potentially instilled by them.

In NYC, the Charles-Fourth Gallery staged an exhibit based on Dr. Wertham’s work, called “School for Sadism: Folk Art in the Atomic Age,” featuring photos of shocked children and enlargements of violent comic book art. The show was covered in Art Digest (May, 1949). In Europe, France passed La Loi du 16 jillet 1949 sur les publications destinées a la jeunesse (“Law of July 16, 1949 on Publications Aimed at Youth”) as a conservative response to the post-liberation influx of American comics.

Love & Death: A Study in Censorship, Gershon Legman’s analysis of sex and crime in popular literature was also published; its comic book section entitled “Not for Children” was exceptionally critical of comic book violence, especially in the crime genre. And the New Republic struck again (“Sex, Censorship & Superman”; Oct.10), just to remind people how the cultural battle was progressing.

On December 6, 1949, following a similar four-year campaign begun by the Progressive Conservative Party to ban the import of American crime comics and prohibit publication of “objectionable” material (using Crime Does Not Pay, as well as Green Hornet Comics, as evidence), Canada’s House of Commons passed a bill making it illegal to “print, publish, distribute or sell any magazine, periodical or book which exclusively or substantially comprises matter depicting pictorially the commission of crimes, real or fictitious.” More information here.

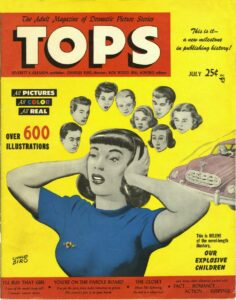

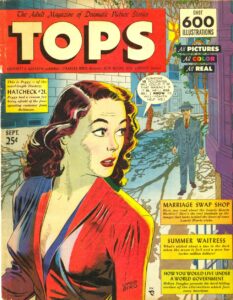

During this period, attempts were made by the industry to expand and elevate its market, appealing more broadly to adults with new formats and approaches. Lev Gleason’s oversize hybrid magazine Tops carried “stories illustrated in the style and technique of comic strips,” like a visual version of Reader’s Digest. Its first issue featured a comic adaption from Billy Rose’s book Wine, Women and Words and short fiction by Dashiell Hammett, its second a critique of Anthony Comstock. Fawcett, meanwhile, would attempt marketing to black audiences and adapting comics into early paperback “pocket books.” None of these experiments lasted long.

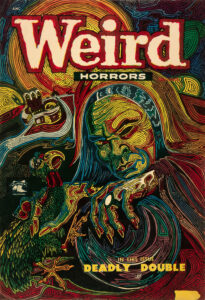

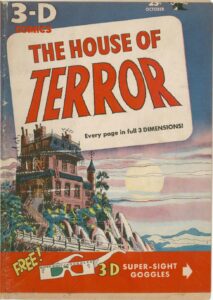

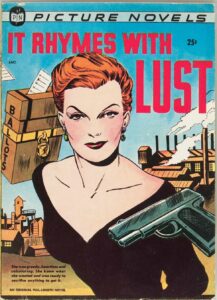

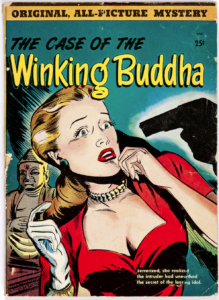

Relative newbie St. John Publications did much better by developing a more realistic, mature-targeted approach in a mix of commercially popular genres, including crime, romance, fantasy-adventure, westerns, supernatural and humor. They would also dabble in the first 3D comics and innovative graphic novel precursors, like the noirish, book-length It Rhymes with Lust, drawn by Matt Baker and The Case of the Winking Buddha, written by pulp crime novelist Manning Lee Stokes. Progressive and original, St. John pointed toward a new approach that comics could take, while still remaining true to its traditional readership. They’d have an impact on the newsstand, but ultimately, they were swimming against the anti-comics tide and would be gone in a decade, switching focus to crime fiction magazines.

Then, in the midst of all this experimentation, another upstart company began to create crime and horror comics combining boldly subversive stories, graphically violent artwork and a darkly humorous approach. Fresh, trend-setting and blatantly defiant of the political climate, it would make them very, very popular. Even legendary.

They stemmed from William M. (“Bill”) Gaines, a man raised with the comic book industry itself. In the early 1930’s, his father Max Gaines worked for Eastern Color Printing on Funnies on Parade and Dell Publications on Famous Funnies, comic strip reprint collections considered the first true American comic books. In 1933, Max pioneered the packaging and selling of comics to newsstands. As publisher of All-American Comics, one of two divisions that made up DC-National, he helped Harry Donenfeld consolidate market power while overseeing the creation of many superheroes still around today, like Wonder Woman and The Flash. After finally selling off All-American to DC in 1944, Max created his own independent company, Educational Comics—EC for short—in 1946 to provide kids friendly comics about science, history and the Bible, plus some commercial genre titles.

But, as might be expected from someone associated with Donenfeld’s mob-adjacent world, Max Gaines was also a mean, abusive drunk who ruled his company with an iron fist, and his family much the same. Max bullied and terrorized his impish, humorous young son, considering Bill a total failure. When Max died in a boating accident in 1947, he left his family a million dollars and a niche comic book company that leaked money, but little real affection to speak of.

By that time William Gaines, after four years in the Army Air Corps (mostly on KP duty) and just graduating from NYU on the GI Bill, was planning to be a High School chemistry teacher. But on inheriting the family business, a rebellious and mischievous idea now took hold: he decided to create the kind of comic books he always wanted to read. Rebranding EC to ‘Entertaining Comics’, he veered away from the wholesome Bible stories and bog-standard crime, western, romance and kiddie yarns, and developed a line of mature themed books that would make the company famous.

And become a catalyst to bring the federal government crashing down on the industry.

To Be Continued…