MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. FBI file #100-HQ-138754 “Communist Infiltration of the Motion Picture Industry” [COMPIC], Part 7 of 15, page 160 [page 67 of the PDF document] can be read in its entirety here. Collier’s magazine “Horror in the Nursery” page from the Seduction of the Innocent.org website. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators and license holders, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

It was a campaign, and a process. Our red threads can follow the connecting sequence of events, observing a nation’s anxieties exploited and subverted, as reactionary propaganda and mass media began swaying public opinion and “firing up the base.”

Throughout WWII, articles critical of comic books started trickling into prestigious and influential publications: National Parent-Teacher (“Those Troublesome Comics” in Jan. 1942), Journal of Educational Sociology (”The Viciousness of the Comic Book,” ”Those Vicious Comics,” “The Comics as a Social Force,” “Comics and Instructional Methods,” 1944) and ultimately, Time magazine (“Are Comic Books Fascist?,” Oct.22, 1945). Conservative news outlets helped sow and spread the discomfort.

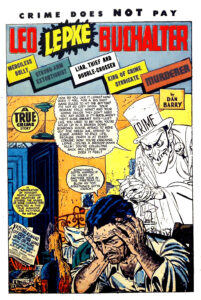

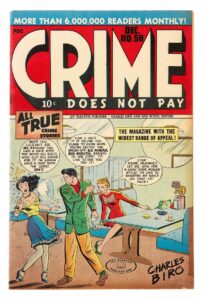

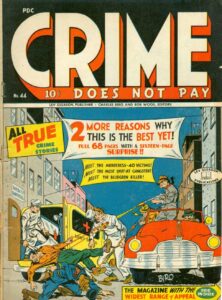

As the war wound down, Crime Does Not Pay particularly became a favorite target; its violent “True Crime” content was replacing the patriotic fantasy violence of wartime superheroes in sales. Having held the comic book crime market virtually alone since 1942, it was easy to single out.

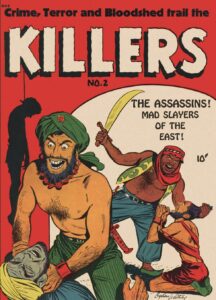

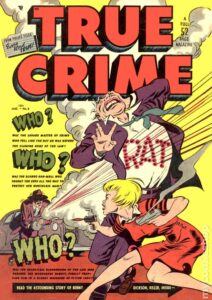

Other publishers felt the mounting public disquiet, but business was business, and they jumped into the crime genre without hesitation or restraint. Where few matched the publication’s imaginative storytelling under Charles Biro and Bob Wood, others compensated with more tabloid sensationalism. Between 1945-48, as competition became more lurid, Crime Does Not Pay stories also became darker to increase sales…which in turn increased critics’ outrage.

Parents, finding comfort in returning to the traditional values that raised them, wanted the post-war prosperity and security they’d struggled for. Kids, raised with violent conflict and now the specter of atomic annihilation, saw things differently. They socially rebelled, independently spending time and money on values of their own, that spoke to them—movies, music and comic books included. What one generation described as juvenile delinquency, the other felt was freedom of personal choice. And as clergy and parental groups became more alarmed, comic book sales continued to boom.

Then, with the end of the wartime pledge by the CIO, Americans joined together in a series of strikes that spread across the US from 1945 to 1946. Affecting almost every major industry, from public utilities to automobiles to Mickey Mouse cartoons, over 5 million American workers walked off the job in protest of shrinking pay and unsafe conditions. NAM corporations became incensed.

Notably, a six-month strike by Hollywood set decorators led to a riot on October 5 at the gates of Warner Brothers Studios between picketers and replacement workers, becoming known as “Black Friday.”

Also, by 1946, post-war Russia occupied more territory than previously. And a Soviet nuclear espionage ring was uncovered operating in Canada (from Ontario’s USSR embassy), the UK (involving Klaus Fuchs, a Los Alamos physicist and also a Soviet spy), and in the US (Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, later executed by electric chair at Sing Sing).

The timing was perfect for conservatives. Even as the Superman radio show ran a serial in which the Man of Steel exposed and defeated the KKK (and Klan national membership dropped), “communist infiltration” was made the central theme of the 1946 elections and Republicans took back control of congress.

Returned to power, infused by Christian Identity politics (now plus the powerful Catholic Legion of Decency) and capitalist, pro-authoritarian NAM and their corporate lobbyists, the country’s new ruling party began to alter and ‘purify’ America’s values.

HUAC was made a standing, permanent committee in the House of Representatives. Once led by ultra-conservative (and historically racist) Southern Democrats, it now aligned to reactionary Republican extremism as congressional clean-up campaigns soon began in earnest.

After rejecting investigation of the Ku Klux Klan (“After all, the KKK is an old American institution,” remarked Mississippi Democrat and white supremacist committee member John E. Rankin), HUAC instead began investigating the possibility of communists infiltrating American culture during the late FDR’s New Deal.

The Cold War, and backroom power-grabs, had truly begun.

Below: an excerpt from the 1946 FBI report provided to HUAC concerning MGM’s Frank Capra film “It’s a Wonderful Life”.

In 1947, HUAC began hearings into alleged Communist propaganda and influence in the motion picture industry. Walt Disney himself (having already called in the LAPD to water-hose his striking, underpaid animators wishing to unionize in 1941) testified that he believed members of his own staff were Communists, and the Screen Actors Guild was a Communist front. [Read transcripts]

Such beliefs led Hollywood to create anti-communist and anti-Soviet propaganda films to demonstrate their patriotism. “Black Friday” helped fuel the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act which, among other things, prohibited unions from contributing to political campaigns and required union leadership to affirm that they weren’t supporters of the Communist Party. Appeasing studios blacklisted or ostracized politically liberal talents like Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, Paul Robeson, Joseph Losey, Ring Lardner Jr., Edward Dmytryk, Dalton Trumbo, even Dashiell Hammett. The witch-hunt lasted until 1960.

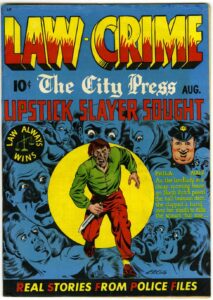

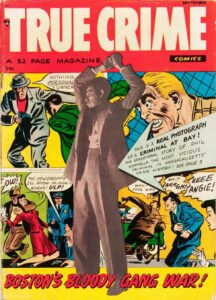

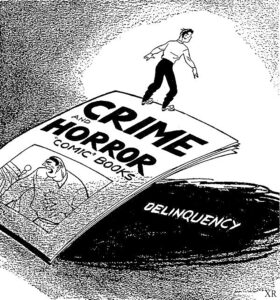

Concerned over rising “juvenile delinquency,” focus now returned to comic books, which became the scapegoat for anti-crime campaigners as the market shifted into crime-suspense, romance, westerns, teenage humor and other genres. Particularly, crime comics went from a 3% market share in 1946 to 9% in 1947. Crime Does Not Pay hit its all-time highest sales, with other top sellers being The Killers, True Crime, and Manhunt. By the time Publishers Weekly (Sept.1947) printed “540 Million Comics Published During 1946,” conservative alarms were sounding.

That year, author Coulton Waugh published The Comics, the first major study of the medium. Focusing on the comic strip as an art form, it harshly criticized comic books as essentially a bastardization containing “Soulless emptiness…outrageous vulgarity.” Then came the conservative flag-bearer New Republic (“Junior Has a Craving,” Feb.17), the New York Herald-Tribune (“Comic Books are Called Obscene by N.Y. Psychiatrist at Hearing,” Oct.30), and by the end of the year, McCall’s (“What do they See in the Comics?,” December).

About the only positive article was in November’s Writer’s Digest: Stan Lee’s “There’s Money in Comics!”

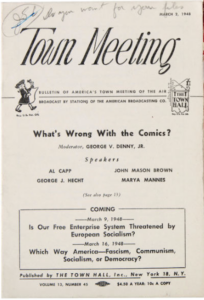

By 1948, crime comics’ sales percentage had jumped into double figures, as high as 14%. Comic books were clearly getting bigger, and crime was noticeably big in comic books. In response, ABC Radio broadcast a debate on America’s Town Meetings of the Air (“What’s Wrong with the Comics?,” Mar.2). There, Saturday Review columnist, drama critic and author John Mason Brown attacked the medium as “the marijuana of the nursery; the bane of the bassinet; the horror of the house; the curse of the kids; and a threat to the future.”

Kitchen-table talk across the US, the wider public was now definitely engaged.

A few weeks later, on March 19, the Association for the Advancement of Psychotherapy held a symposium on “The Psychopathology of Comic Books,” featuring Dr. Fredric Wertham (the psychiatrist mentioned above in the Herald-Tribune).

Wertham, a conservative, held impeccable credentials as a progressive on social issues. A pioneering neurobiologist, he’d worked extensively to fight the stigmas associated with mental illness in children. He was an early advocate for the poor and disenfranchised mentally ill to receive fair criminal trials and allow their background and mental health to serve in their defense. He’d helped establish the Lafargue Clinic in Harlem, a low-cost, non-discriminatory psychiatric center for the disadvantaged. He also authored important studies that concluded racial segregation was detrimental to children’s mental health, and was instrumental in Brown v. Board of Education, helping eliminate the racial segregation of children in public schools. Yet during his work at the Lafargue Clinic, Wertham made debatable connections between juvenile delinquency and comics popularity. Right-wing support soon came calling, elevating him to a new career in the public spotlight as a crusader and outspoken critic against the medium.

Joining in the symposium: folklorist Gershon Legman (“Comic Books and the Public”), Hilde L. Mosse, M.D. (“Aggression and Violence in Fantasy and Fact”), Paula Elkisch, PhD (“The Child’s Conflict About Comic Books”) and Marvin L. Blumberg, M.D. (“The Practical Aspects of the Bad Influence of Comic Books”), who all felt much the same.

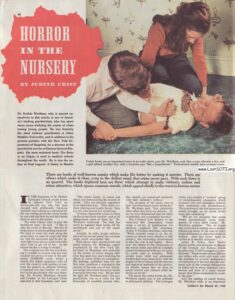

The next day, Saturday Review spread controversy by printing “The Case Against Comics” by John Mason Brown, “The Case for Comics” by strip-cartoonist Al Capp, plus a lengthy review of Waugh’s book, sparking heated debate in their letters column for months. One week later came an article citing Wertham in Collier’s (“Horror in the Nursery” by Judith Crist; Mar. 27). Time covered the symposium two days after that (“Puddles of Blood”; Mar. 29), giving it three pages.

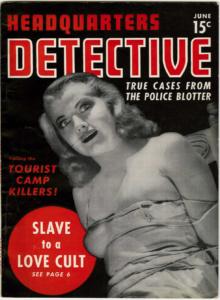

That same day, March 29, 1948, in Winters v. New York, the US Supreme Court struck down an unconstitutional law on the New York books prohibiting the sale of any “magazine…principally made up of criminal news, police reports, or accounts of criminal deeds, or pictures, or stories of deeds of bloodshed, lust or crime.” Under this statute, a bookseller had been convicted for selling a sleazy tabloid magazine called Headquarters Detective #1 in 1940.

The court’s decision wasn’t directly comic book related, but by re-enforcing the First Amendment in New York, it legally cleared the way for crime comics, and soon horror comics, to flourish. Which they did. Conservative outrage was swift, and escalated quickly.

In April, Time informed readers “Detroit Police Commissioner Harry S. Toy examines comic books in his community and indicates they’re ‘loaded with communist teachings, sex and racial discrimination.’” Next, Dr. Wertham and company were disseminated more broadly when the AAP symposium’s abstracts were printed in American Journal of Psychotherapy [read here].

Wertham himself published an article in Saturday Review (May 29: “The Comics…Very Funny”), with Reader’s Digest reprinting a selection that August. Then, showcasing the sort of material even Crime Does Not Pay wouldn’t cover, newspapers around the country began reporting the story of 3 boys in New Albany, Indiana who tried to torture and murder other kids using ideas they got from comic books (Aug.19).

The messaging pressed on. Director of the Child Study Association of America, Sidonie Matsner Gruenberg, wrote “What About the Comic Books?” for Women’s Day. The symposium’s Gershon Legman published an essay, also called “Psychopathology of Comic Books,” in the journal Neurotica.

Angry citizens began demonstrating. In September, L.A. County passed a comic book ban, soon followed by Cleveland, Milwaukee and St. Louis.

That October, in Spencer, West Virginia, the first comic book burning occurred. It was followed by similar events in Chicago, Vancouver and other cities, sponsored mostly by Boy Scout troops and Catholic Archdioceses. The NY Times reported “Comics Debated as Good or Evil” on October 30, with a follow-up November 25. Reader’s Digest featured “Common Sense about Comics”, reprinting warnings from Parents magazine. Then by Christmas, Time began reporting on comic book burnings in Burmingham, NY.

As had happened in 1933 Berlin, manipulated paranoia and reactionary politics touched off a literal conflagration. More bonfires and bans would follow across panicking America.

Comic books, turning our nation’s children into criminals? Could this be true?

Did it matter…?

As German author, poet, journalist and literary critic Heinrich Heine wrote in 1823: “That was but a prelude; where they burn books, they will in the end also burn people.”

To Be Continued…