MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: Images and samples are for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. Big Town and Batman/Detective Comics are copyright DC Entertainment, Warner Bros. Global Brands and Franchises division of Warner Bros., and AT&T’s Warner Media. All other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators and license holders, unless otherwise noted.)

[NOTE: contains explicit images.]

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

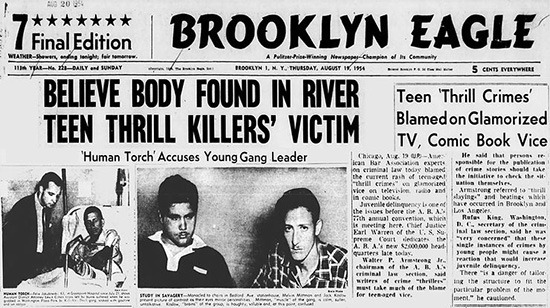

The Summer of 1954, a Manhattan crackdown on “social undesirables” (i.e.; gay men, the homeless and alcoholics) drove many to seek refuge in Brooklyn. A gang of four teenagers, members of the Brooklyn Jewish community, beat a homeless alcoholic to death and attacked and drowned a black factory worker in the East River. They additionally beat and tortured several other vagrants (burning some with gasoline) and assaulted 2 girls using horsewhips.

On arrest, they claimed they did it to “rid the neighborhood of ‘undesirables’” and “clean the streets of bums.” During interrogation, the gang’s leader, Jack Koslow, 18, self-identified as a hero on “a supreme adventure,” claimed the killings gave him “a thrill,” and admitted he read comic books.

The case triggered a media sensation. Papers dubbed them the ‘thrill killers,’ elevating them to symbols of modern juvenile delinquency. The NY Times labeled them homosexuals and neo-Nazis; Life: “Those Terrible Youth”; and Inside Detective tagged the leader the “Boy Hitler of Flatbush Ave.” For months, the “Brooklyn Thrill Killers” story engaged the country. Even into 1955, Hedda Hopper was suggesting they were the inspiration for James Dean’s character in Rebel Without a Cause.

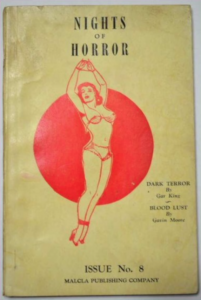

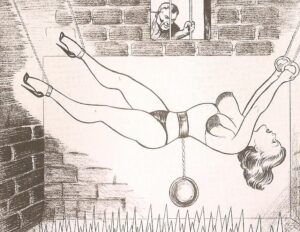

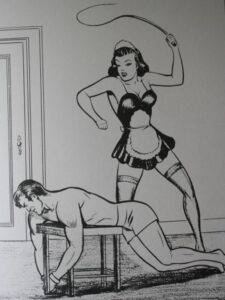

Frederic Wertham became the court-appointed psychiatric expert for the case, and naturally suggested comic book influence was to blame for the gang’s sadistic depredations. He cited as evidence, not a comic book, but a porno-BDSM fetish magazine called Nights of Horror, available at seedy bookshops in Times Square (samples below).

The publication was so low-end it didn’t even have photographs, just drawings. And no connection between it and the teenagers was ever established. But Nights of Horror magazines were quickly seized and banned, first in the Big Apple, then by the State of New York, following soon after the teenager’s inevitable guilty verdict.

The comic-reading “Thrill Killers” reignited national outrage and backlash toward the industry. And although the Kefauver Subcommittee Final Report did not (could not) directly blame comic books for juvenile delinquency and crime, it recommended that the comics industry tone down its content voluntarily. Kefauver himself seemed to lose interest in comics soon after he was selected as a potential presidential candidate, and never acted beyond the hearings.

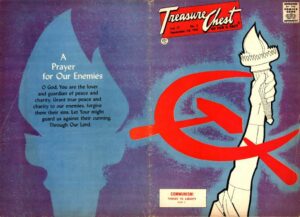

By August, a new, conservative, Cold War America was in full effect. As recently-elected President Eisenhower, Republican, signed the Communist Control Act into law, banning the American Communist Party outright and prohibiting people deemed to be communists from serving as officials in labor organizations, the Connecticut PTA established the abolition of “unwholesome comic books” as one of its major goals for the second half of 1954, and parents in New York renewed arguments and investigations against the comics industry through local government and civic groups.

The damage was done. That summer 15 publishers went out of business.

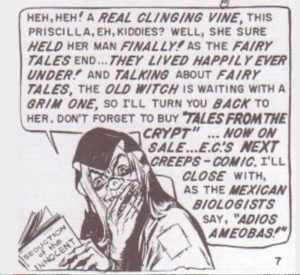

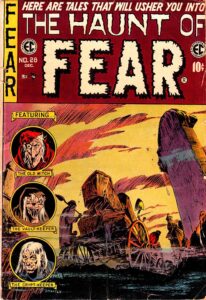

Bill Gaines and his company were crucified by the national press and pariahs in the industry. EC cancelled all their horror and SuspenStories comics on Sept. 14. In its penultimate issue, The Haunt of Fear’s gleeful host, the Vault Keeper, was shown reading Seduction of the Innocent.

Across the Atlantic, meanwhile, in an industrial area of Glasgow, Scotland known as “The Gorbals” (where the urban legend of a witch called “Jenny wi’ the Airn [Iron] Teeth” haunting Glasgow Green had been around since the 1800’s), a rumor spread that a vampire had brutally murdered and eaten two young boys. On Sept. 23, local children armed with crosses, knives and wooden stakes were caught prowling a cemetery looking for the undead killer. ‘The Gorbals Vampire’ story spread throughout the city, was picked up by the UK national press, and covered in worldwide news.

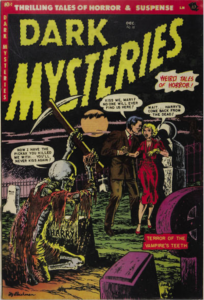

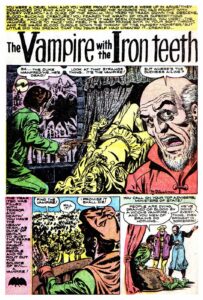

Worried parents, teachers and religious leaders desperately sought answers for why their innocent children might believe such a bizarre story. Politicians quickly found the obvious culprit: “evil and depraved” American horror comics on British newsstands. Specifically, a story appearing the previous year in Dark Mysteries #15 (non-EC, notably), called “The Vampire with the Iron Teeth.” Shocked at the comics they found, convinced of the content’s responsibility in warping their children’s young minds, local politicians took their case to Parliament. Link here.

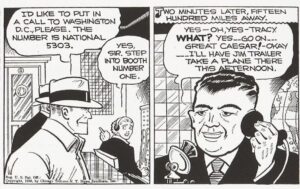

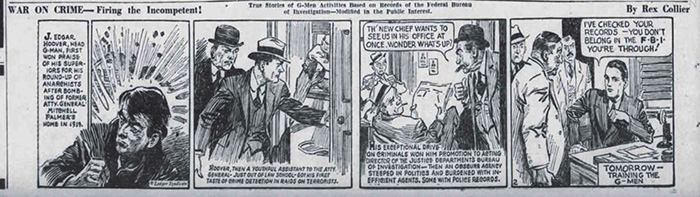

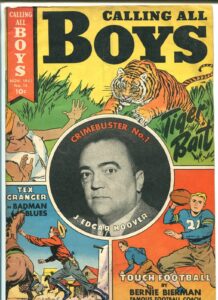

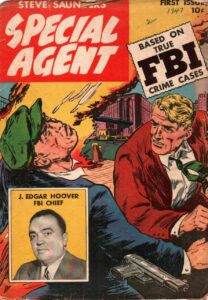

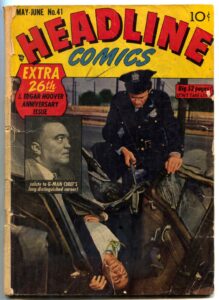

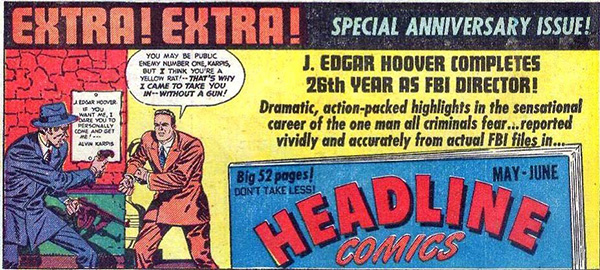

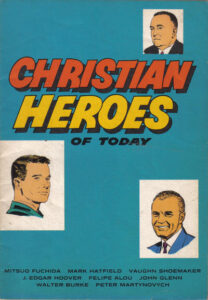

That month, Scouting, official magazine for the Boy Scouts of America, published “Who is to Blame for Juvenile Delinquency?” by J. Edgar Hoover. Curiously, it makes no mention of comic books. Perhaps Hoover was establishing plausible deniability for his clandestine involvement here, as his imprimatur often appeared on the covers of crime comics. In fact, he’d utilized or endorsed newspaper strips and comic books for anti-crime propaganda since the 1930s (and would continue to do so well into the 1960s).

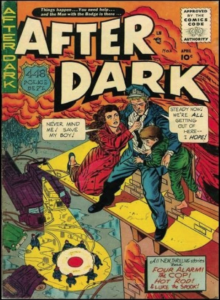

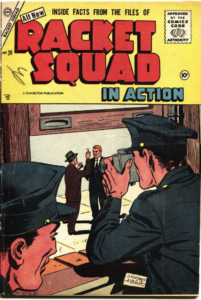

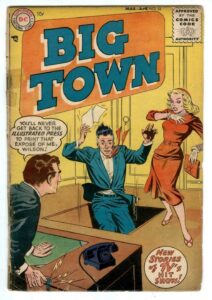

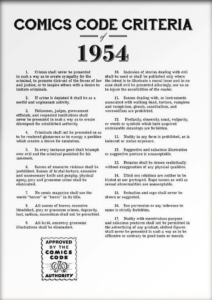

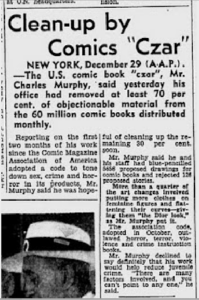

By October 26, 1954, surviving publishers had enough. They met and agreed to form the Comic Magazine Association of America, adopting an industry-wide code and creating a self-censorship board called the Comics Code Authority, much like the earlier Hollywood Hays Code. The results: purging and whitewashing all comic books into wholesome, safe, unthreatening, kid-friendly entertainment.

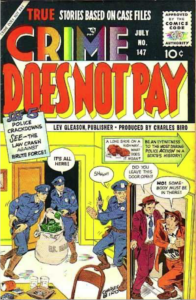

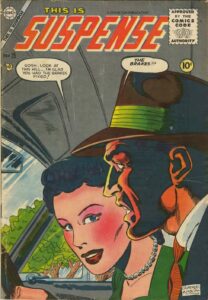

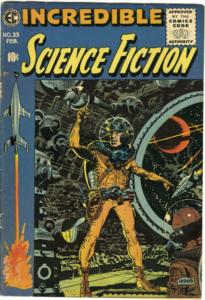

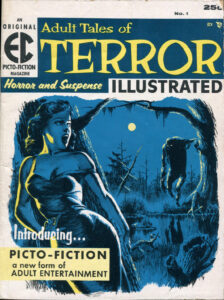

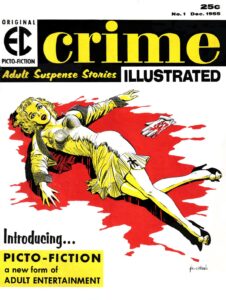

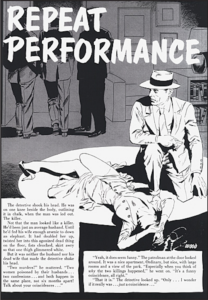

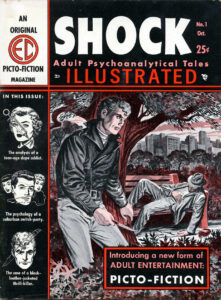

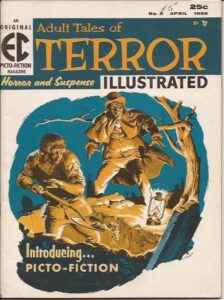

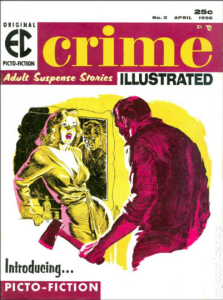

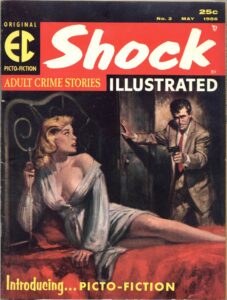

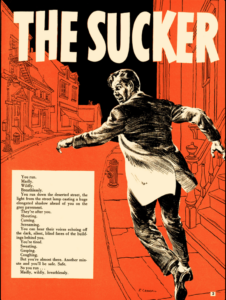

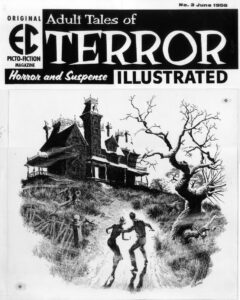

Particularly censorious towards EC comics and Lev Gleason’s Crime Does Not Pay, the CCA decreed no more violent crime or horror content, or even bold use of the words “Crime”, “Horror” or “Terror” on covers. Violence would be implied, but mostly not shown. No sexuality, drugs or vice, all bad or antisocial behavior would be seen as wrongful and be punished. Only positive, virtuous, educational or patriotic stories.

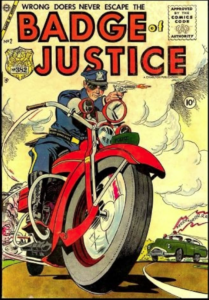

Tough crime dramas that helped create the medium? Gone. Hardboiled PIs became community-spirited “good guy” cops, or fearless federal agents fighting America’s enemies (shifty communists and “foreign” spies, global cabals threatening democracy and World Peace, etc.).

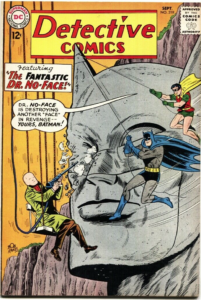

Superheroes returned, but as “commie-smashers,” or with more humorous or science-fictional content; positive, aspirational symbols for America’s youth. Truly realistic, competent criminals could no longer be shown, so they now became fantastical “super villains” with outrageous, improbable schemes.

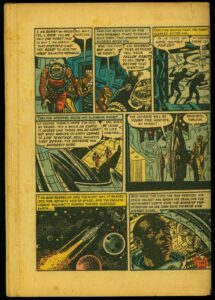

Horror? Formulaic, “classic” ghost stories with mechanical finales; no more vampires, werewolves, zombies, sadists or ghouls. These quickly became safer sci-fi/fantasy tales of giant atomic creatures and intergalactic invaders, metaphors for foreign enemies swiftly put down by US military science or its cosmic equivalent. Or sometimes just directly by Divine Intervention, the ultimate all-American, Christian Nationalist deus ex machina.

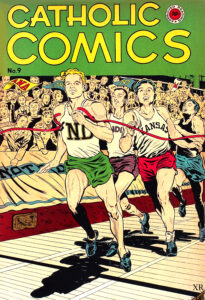

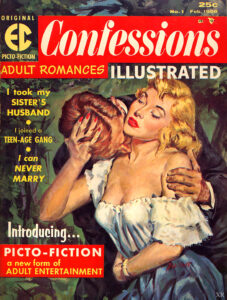

Romance and teen humor comics now reinforced wholesome, safe values. Maybe kissing on the first date, but no sleeping around, or sex at all; just teenage angst and frustration instead of desire. No more divorce, no more single mothers or murderous spouses. No more mature content, or advertising. No adult reality.

Colonialism, slavery, racism? Unquestioned, reduced to simple messages of “Why can’t we all get along?” when encountering strange alien worlds, or Red Chinese. Or native tribes, who just didn’t seem to understand ‘civilization’. When social problems were addressed at all in western, war or jungle tales, solutions were found quickly and reflected a homogenous, middle-class vision of white justice, white ideals and white status quo.

Curiously, there were specifically Protestant and Catholic comic books sold broadly on newsstands across America, but no Jewish ones beside them.

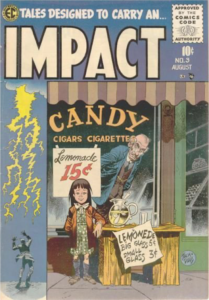

To indicate industry compliance and reassure the public, comics now featured the “Approved by the Comics Code Authority” stamp on their covers. Failure to comply meant stores could refuse to sell those books.

But conservatives weren’t quite done.

Scouting followed up with another anti-comics article in October, not by Hoover (“Comic Books Ain’t Comical”), and yet another Reader’s Digest article hit that November (“The Face of Violence”). By February 1955, Today’s Health began noting the next target due for cultural clean-up (“Comics, Television and Our Children”). In Germany that March, publishers instituted the Freiwillige Selbstkontrolle für Serienbilder (“Voluntary Self-Control for Comics”).

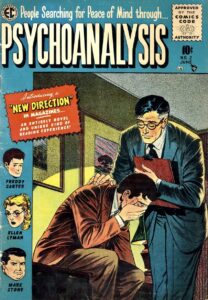

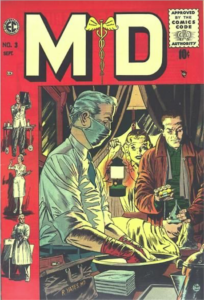

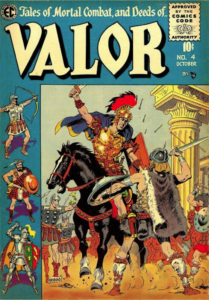

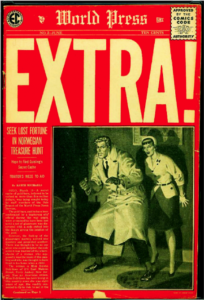

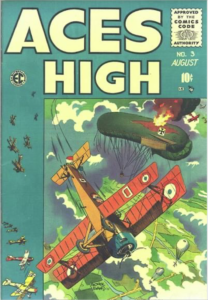

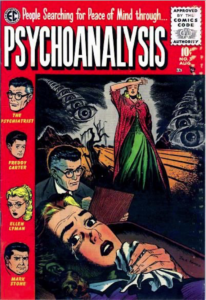

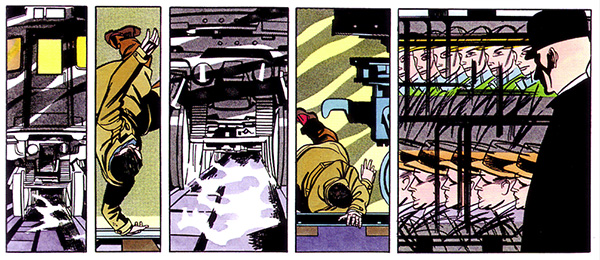

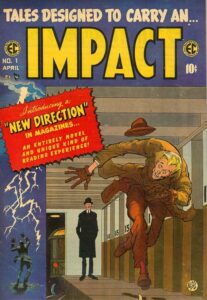

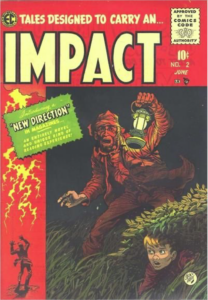

Trying to somehow remain both viable and current, EC launched Impact, Psychoanalysis, Piracy, Valor, Extra, MD, Aces High, and changed its sci-fi titles to fall within Code guidelines. All were high-class, but only Impact came close to hard-hitting. In fact, its first (pre-code) issue featured one of the more experimental stories EC ever produced: Bernard Krigstein’s “Master Race,” a tale concerning the Holocaust. Made decades before Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer prize-winning Maus, it’s now recognized as a classic in narrative art (and an inspiration for Spiegelman personally). Still, all these books failed after just a few issues.

In April, “It’s Still Murder” by Wertham was published in Saturday Review. Somewhat late to the lynching, Everywoman’s magazine chimed in with “Attention All Parents! What Should You Do About Comic Books?” The ACLU, not exactly on-the-spot, released an anti-censorship pamphlet in May entitled Censorship of Comic Books: A Statement of Opposition on Civil Liberties Grounds. That month, the Queensland Literature Board began banning “objectionable” comics in Australia.

On June 6, both Parade of Pleasure and the ‘Gorbals Vampire’ case successfully influenced the UK Parliament to adopt the 1955 Children and Young Persons Harmful Publications Act.

Technically, it is still in force today.

Crime Does Not Pay, unable to maintain its edge under the new Comics Code, was cancelled in July.

During this entire social outcry, crime genre’s actual share of the overall reading market from the 1948-54 period was only ever less than 10 percent. Notably, as crime comics declined and then nearly vanished, code-approved romance comics maintained a market share of 14-15% annually. All US comics began declines to 6, 6, 7 and 6 percent overall from 1951 through 1955.

As sales collapsed, page-rates dropped and talent fled. Publishers folded, selling off any valuable catalogues, asset titles and unprinted backlog to others. Independent News, Harry Donenfeld’s distribution and loan operation, helped small companies suddenly appear, scoop up loose material, re-edit them to code approval, then vanish after fast turnaround and a quick profit on the newsstands. Harry, untouched and long since legitimized thanks to millions generated from licensing Superman to film, TV and everything else, made a killing.

When this feeding-frenzy ended, only a few companies survived. Between 1954 and 1956, eighteen comics publishers collapsed. The number of actual published titles fell from 650 in 1954 to 300 in 1956. Under the moral scrutiny of the CCA, remaining publishers fought for market territory as big, high-profile companies like Dell and DC, with mass-media IP’s (and for DC, backroom control of virtually all lesser publisher’s distribution) became dominant survivors in the industry, unchallenged until the next decade.

In 1956, EC published its last comic book, the defiant Incredible Science Fiction #33.

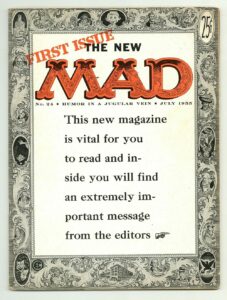

As newsstand magazines remained unaffected by the Code, Gaines pivoted, turning Mad into the popular Mad Magazine. Attempts to do the same with his crime and horror material failed however, despite high quality. Mad alone continued, iconic for decades.

Lev Gleason ceased publishing that same year, issuing the third and final issues of his teen-humor title Jim Dandy, and a children’s Western, Shorty Shiner. Gleason and his wife retired to Cape Cod, where he entered into real estate.

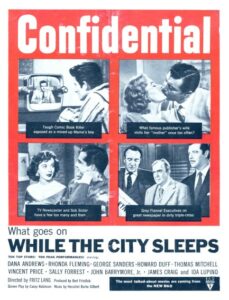

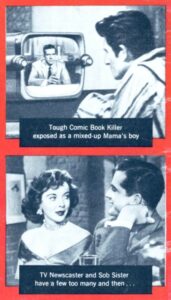

Comics had now become identified as low class, reading material for the young and illiterate, a “gateway drug” for crime. Poster art for RKO’s 1956 noir film While the City Sleeps, ironically set against a faux tabloid cover, could tag its serial murderer as a “Comic Book Killer” and few would question it.

In 1957, the Nights of Horror case went before the US Supreme Court, which despite the First Amendment, upheld the New York ban in its ruling Kingsley Books, Inc. v. Brown.

Unknown during the original trial, Nights of Horror was later found to have been illustrated by none other than Joe Schuster, co-creator of Superman. Financially destitute, Joe had taken the job for the money after being cheated out of proceeds for years by DC.

To Be Continued…