By Dale Berry

MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

The 1930’s had proven to be a stressful decade for the USA. Prohibition, the Great Depression, uncertainty, and desperation helped to foster a rise in violence and organized crime. People were worried, and afraid.

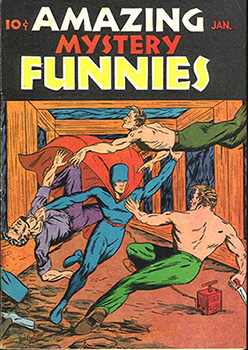

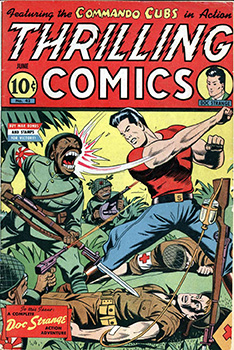

The new medium of comic books, taking their cue from newspapers, films, radio and especially the pulps, reflected this concern by creating original content with a focus on crime fiction, with elements of heroic fantasy-adventure and mystery-horror folded in. By the end of the decade this had evolved into a unique genre of costumed mystery men with extraordinary powers and abilities who could right society’s wrongs and bring criminals to justice. Traversing the Earth (but mostly big cities), fighting for the common people, the “superhero” was born.

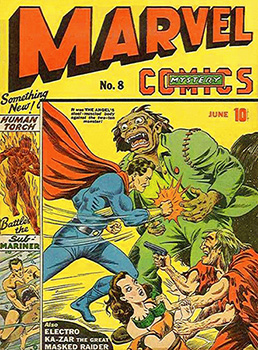

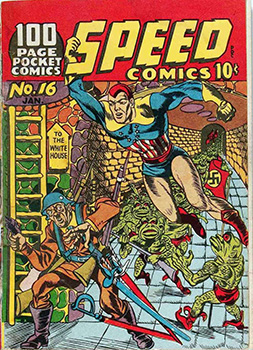

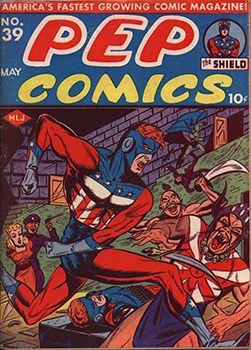

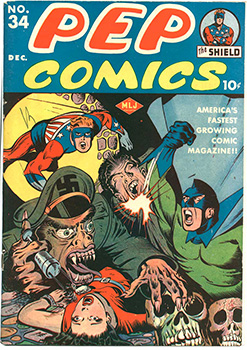

These colorful new characters had exploded in popularity, multiplying and energizing the medium. Any comic book aimed at an adolescent-to-adult audience now added at least one superhero to its line-up of detectives, cowboys, explorers, magicians, reporters and comedy strips. Many had several of these new costumed wonders, seizing the spotlight, displacing the old features and relegating them to supporting acts.

Just in time, too. Conflict was breaking out around the world, further empowering reactionary, authoritarian “secret societies” in the US like the Ku Klux Klan, as well as neofascist organizations such as the Nazi sympathizing Brown Shirts on the East Coast and Silver Shirts on the West. More and more, comic book characters began encountering foreign spies and armed invasions amid their battles against gangsters, mad scientists, and run-of-the-mill maniacs.

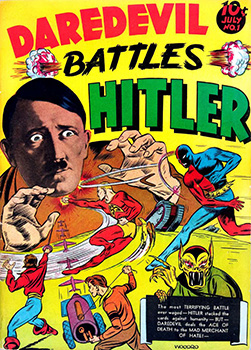

Chaos threatened, and as the decade turned and national anxiety rose, patriotic and nationalistic superheroes began to emerge to help readers cope with the stress. As early as 1941, as the Nazi and Axis powers finally revealed themselves as the clear villains, some comic characters began fighting them even before the US became involved, or war had been officially declared. Once the battle did reach our shores, America’s superheroes were more than prepared to lend their violent skills, gift for vigilante justice and flair for propaganda to the Allied cause overseas and the war at home.

But what about the war on crime?

Enter the talented Lev Gleason and Charles Biro… and what would become the Golden Era of Crime Comics.

Leverett Gleason was already a seasoned veteran of the fledgling business, having worked as an artist, advertising director for comics-publishing pioneer Eastern Color Printing in 1933, and launching Tip Top Comics, an early omnibus title which ran from 1936 to 1938, for United Feature Publishing. As the business manager for Your Guide Publications Inc., Gleason purchased two superhero titles—Silver Streak Comics and Daredevil Comics (no relation to the current Marvel Comics/Disney character)—from a company affiliate and formed Lev Gleason Publications.

In 1941, Gleason hired Charles Biro, a writer, artist, and former artistic supervisor for MLJ Comics, and the comics “packaging” studio, the Harry “A” Chesler Shop. As editorial director, head writer and cover artist for Gleason, Biro -together with an old associate of his from the Chesler Shop, Bob Wood, delivering the interior artwork—would shape Daredevil Comics and its lead characters into a dramatic series that appealed to both adults and children, and would last into the next decade.

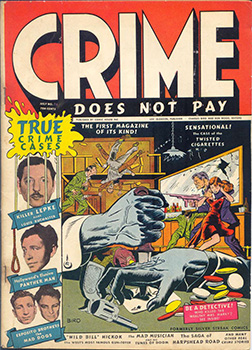

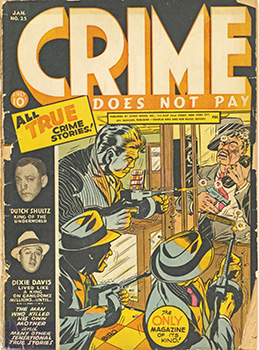

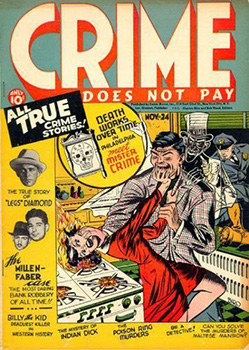

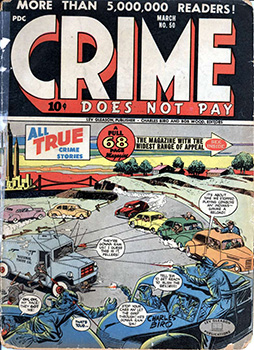

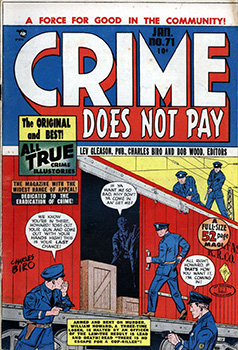

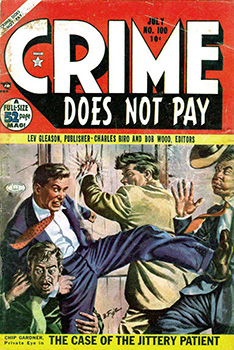

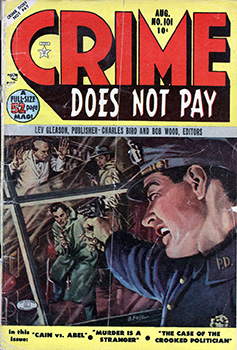

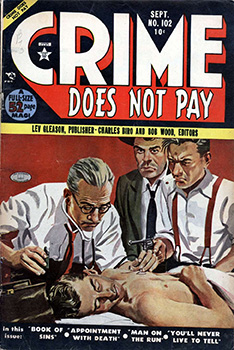

In 1942, the socially conscious and intellectually minded Gleason launched Reader’s Choice, a left-wing political magazine. His progressive politics also extended to giving Biro and Wood a share of the company’s profits, unheard of in the comic book business at that time. After Daredevil Comics success, he told the two editors that if they came up with an idea that proved popular, the two would be rich. Sensing a need in the zeitgeist, Biro and Wood changed the title and content of Silver Streak Comics, but continued with the numbering to avoid paying a postal permit fee on new titles. Their ‘new’ book, Crime Does Not Pay, premiered early that year with issue #22.

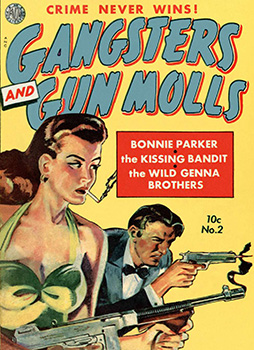

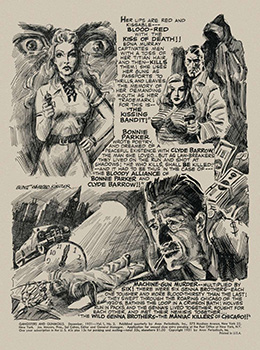

The story goes that Biro and Wood, trading stories in a bar, decided that gangsters and crime could provide an endless flow of new story material for comics. The two swiped the name from a series of popular MGM film shorts, and Biro added a narrator for the tales, a sinister, top-hatted ghost called “Mr. Crime,” who would drop pithy comments on the proceedings.

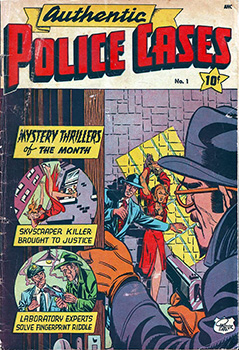

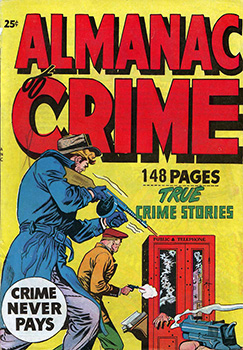

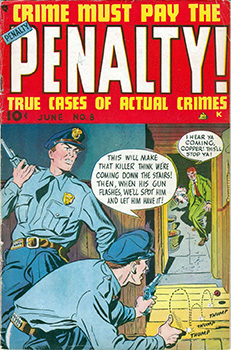

The focus was on actual police cases, the brutal careers and tragic biographies of real criminals, and famous historical crimes, all told in the hardboiled style and drawn in graphic, lurid detail. The formula worked, and the book caused a sensation that was felt industry-wide. “True Crime” had come to the comics, and the effect was massive. At its peak, Crime Does Not Pay sold a staggering four million copies a month, and six million if you counted pass-along copies to friends

So why that time, and why that subject? The superheroes were dominating comic books during the war years, providing a certain promise of hope in the face of what was often a very uncertain outcome. Framing the nation’s enemies as Weird Menace-style monsters and mad scientists—“super villains,” as it were—allowed heroes to slaughter them wholesale without a second thought. Against such non-human caricatures, the valiant and righteous would always win, and be justified in their methods.

But these were still mere fantasy projections. Everyone could feel the real daily effects of rationing, fear, and loss amid the constant barrage of news about battles and body counts, and no one really knew how the war would end.

Perhaps Crime Does Not Pay delivered “proof” that America was able to deliver on actual solutions to its historical problems, that there was a moral imperative that worked. The fact that it did so while also pandering to America’s traditional taste for violent melodrama certainly helped. Dark times required often dark solutions.

Whatever the reasons, by the latter half of the decade, crime had firmly established itself as a solid, dependable, marketable comic-book genre. And it didn’t hurt that under the helm of the quality-conscious Lev Gleason and the sincere, mature-minded guidance of Biro and Wood, Crime Does Not Pay became consistently among the best written, best edited and best drawn comics around.

By 1945, when the war finally ended, the need for superheroes waned, and the characters found themselves, like many returning veterans, without a clear place to call home. Created to battle super-menaces, and having done their job, there was no longer a need for them.

The most popular characters continued on, struggling for direction and purpose, seeking out whatever villainous antagonists there were left. But things had changed. Soon, superheroes began to fade in popularity, replaced by romance, teenage humor, science fiction. We’d won, and it was time to celebrate. To find new, more aspirational fantasies. It was also a time to rebuild, and for real people to do the cleaning up. The war on crime, real crime, true crime, the kind that real people dealt with every day, fitted this new sensibility perfectly.

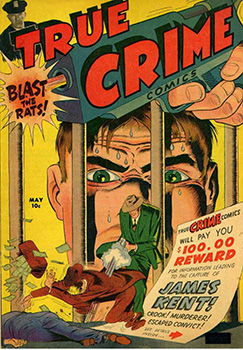

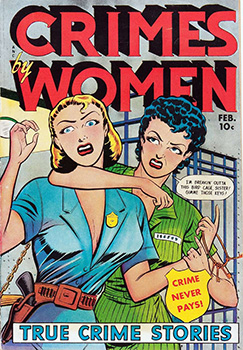

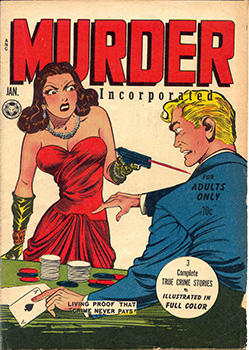

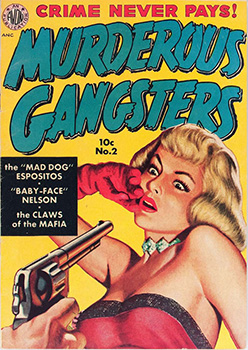

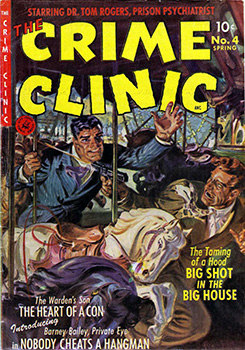

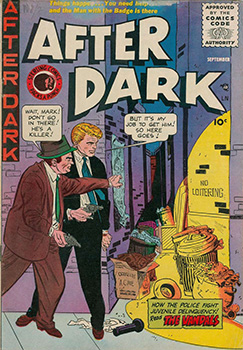

It was a trend no savvy publisher could ignore. Suddenly, crime comics exploded across the stands, copying Crime Does Not Pay’s successful formula but attempting to better it with more violence, more sleaze, more tabloid sensationalism.

And so, from their hiatus as supporting features, the cops, P.I.’s and federal agents now returned as the leading characters once again, dealing out tougher, more realistic justice to reflect a tougher, more realistic time. And, taking their cue from Crime Does Not Pay, featuring more realistic art. (Post-war illustrators of crime comics would include future official presidential portrait artist Everett Raymond Kinstler.)

Still, for some, it wasn’t enough. The post-war audience, having returned victorious but also damaged from the experience, was not the same. The fighting had required civilization’s animal nature to be set loose, now it was hard to put it back in its cage. Things felt adrift. People had personally witnessed too much destruction and death. And as they, like the superheroes, also struggled to find meaning in it all, they craved stories that reflected their experience, their new reality. The old pulp formulas and two-dimensional, Good vs. Evil archetypes began to feel stale.

Joy and escapism could still be found, but now audiences also sought darker tales of the human condition. Stories of social injustice, juvenile delinquency, drug addiction, the suddenly unemployed and marginalized men and women facing unfocused, uncertain futures.

The crime comics of the era began reflecting an America trying to understand why victory had not brought it more success. It was a feeling that would hang over the country like a cloud for some time, well into the next decade…and cause a moralistic push-back.

To Be Continued…

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only. Action Comics, Detective Comics, Superman and Batman are copyright DC Entertainment, Warner Bros. Global Brands and Franchises division of Warner Bros., and AT&T’s Warner Media, respectively. Marvel Mystery Comics and its related characters are copyright Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Worldwide Inc., a division of The Walt Disney Company. The Shadow and Doc Savage are copyright Conde-Nast. All others are public domain, and/or copyright all respective creators.)