MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only and constitute fair use. Daring Mystery Comics, Silver Scorpion, Miss America, Blonde Phantom, All-Winners Comics, Captain America, Golden Girl, The Human Torch, The Sub-Mariner, Sun Girl, Marvel Mystery Comics and all related characters are copyright Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Worldwide Inc., a division of The Walt Disney Company. Phantom Lady and Black Canary are copyright DC Entertainment, Warner Bros. Global Brands and Franchises division of Warner Bros. Discovery and AT&T’s Warner Media, respectively. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

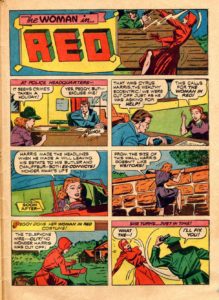

Comic books’ first masked, female crimefighter would emerge in March 1940. In Thrilling Comics #2, from Nedor-Standard Publications, Peggy Allan, a policewoman frustrated by the limitations of the law, donned an all-crimson robe, cowl, mask, gloves and heels to become the mysterious Woman in Red. A vigilante sleuth willing to shoot it out or throw down with the toughest criminals, evil masterminds or fiendish death traps (including water tanks filled with octopi and naked jungle assassins armed with poison darts, as it does), the Woman in Red appeared in various titles and lasted until 1945.

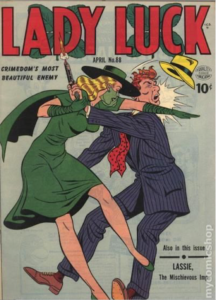

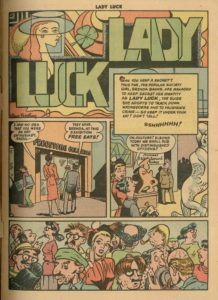

She’d be quickly followed in 1940 by Lady Luck, created by Will Eisner and artist Chuck Mazoujian, from the Eisner-Iger Studios shop. Using Batman’s template, Lady Luck was the alter ego of a wealthy socialite heiress-turned-costumed heroine, Irish-American debutante Brenda Banks, sporting an ensemble of all-green dress, cape, hat and veil to hide her identity and Veronica Lake good looks. She appeared as a four-page backup feature in Eisner’s syndicated newspaper “Spirit Sections” until 1946, written and drawn primarily by Klaus Nordling with a strong His Girl Friday/screwball flavor. Lady Luck’s rollicking, humorous adventures would also be reprinted in Quality Publication’s Smash Comics from 1943 to 1949, and in her own title until 1950.

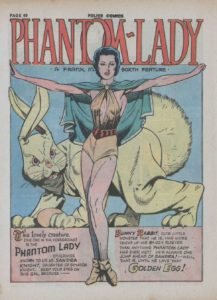

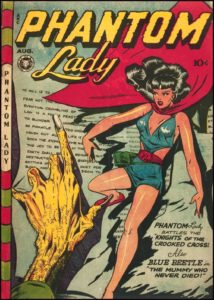

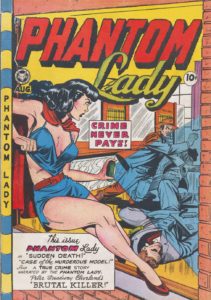

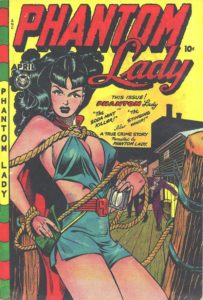

Quality was a company that relied heavily on the Eisner-Iger Studios, and creators who learned and reflected its progressive storytelling style. Their product often featured a high degree of realism (or slick cartooning, as needed), plus visually dynamic, eye-catching page design, a hallmark and influence encouraged by the shop’s Art Director, the inventive Will Eisner. The shop created for Quality several characters that would remain popular for years, including the paramilitary anti-fascist Blackhawk, and the satirical Plastic Man, both still with us. In 1941, Eisner and his partner Jerry Iger (great-uncle to Bob Iger, executive chairman and CEO of the Walt Disney Company, btw) scored yet again when they introduced the legendary Phantom Lady to Quality’s line-up.

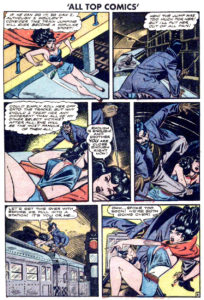

Sandra Knight, debutante daughter of a US senator, dressed in a cape and skimpy outfit “to deliberately distract her predominantly male foes” (uh, okay…). Armed with a blinding “black light projector” (which was handy, since she didn’t wear a mask), Phantom Lady battled multiple crooks and spies over the years, beginning in Quality’s Police Comics, then through various publishers and costume changes until the mid-1950s. This longevity was mostly thanks to a parade of superior artists (including the fabulous Matt Baker, whom we’ve previously mentioned) who gave her a glamorous, Bettie Page-style pin-up flair. Perhaps too much so, as in 1954 Phantom Lady comics were singled out by reactionary critics for having a morally corrupting effect on America’s youth.

But truth be told, she’s the perfect example of a character who’s not really bad, just drawn that way. Often riddled with self-doubt, Phantom Lady nevertheless persevered in following the clues and cracking the case, even if she had to leap across rooftops, ride a horse, crash a plane, fight a gang or outwit an arch-criminal to do it. And regardless of how she presented, in the stories there was never any doubt that the clever, tough Sandra Knight, like a Wonder Woman without super powers, was in charge of driving the action and, by the conclusion, was always the smartest and most capable person in the room. Which is why, even decades later, her legacy as a model for costumed heroines remains, most recently in the influential and bestselling graphic novel Watchmen, where the character is paid deliberate homage as “The Silk Specter.” Too sexy to die, she’s still around, currently owned and published by DC.

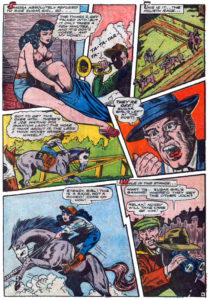

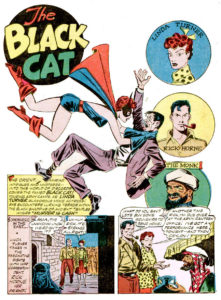

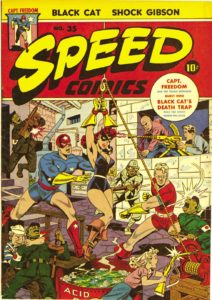

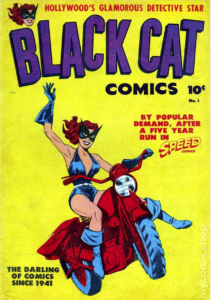

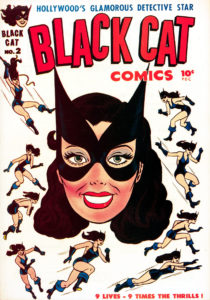

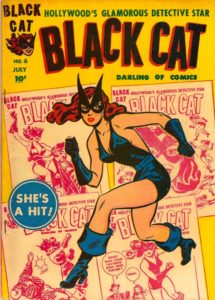

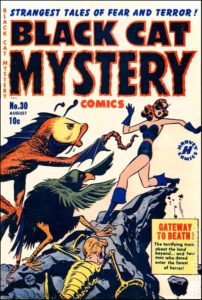

From 1941 also came Linda Turner, tough and self-determined daughter of a Hollywood stuntman, who began as a stuntwoman herself but soon graduated to movie star while moonlighting as the mysterious crimefighter called The Black Cat. Cheerful and upbeat, she alternated between solving action-packed mysteries on and off her movie sets, and when WWII broke out battled Axis villainy with a vengeance. Beginning as a back-up feature in comics from Harvey Publications, she proved popular enough through the war years to graduate into her own title, which lasted until 1958.

Seeking to stand out in a competitive marketplace, Harvey put a lot of commercial effort into their comics, and Black Cat’s magazine would contain not just her adventures (well-illustrated by artist Lee Elias), but also Black Cat short fiction, film gossip and movie star interviews, plus reprints of popular newspaper strips such as Mary Worth and the private eye Kerry Drake, courtesy of Harvey’s licensing deal with William Randolph Hearst’s King Features Syndicate.

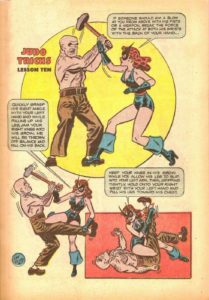

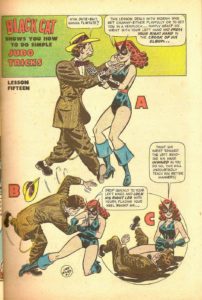

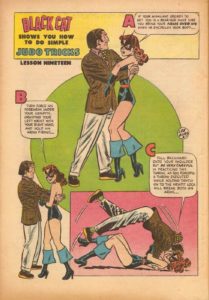

Interestingly, Black Cat was also a heroine who preached what she practiced. While many characters showed off their gimmicky jiu-jitsu prowess by occasionally flipping around bad guys in their fight scenes, Black Cat actually devoted pages of each issue to illustrated self-defense lessons in judo for her audience. Female readers could now be educated in the fine art of pain compliance holds, joint-locks, throat strikes, takedowns and groin kicks to protect themselves from bullies, a comics first.

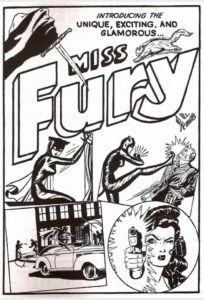

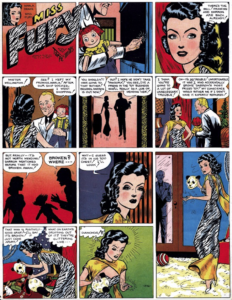

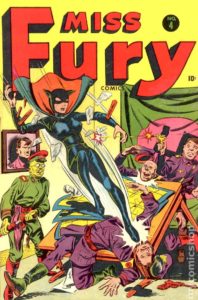

That fateful year of 1941 also saw, more importantly, the debut of comics’ first masked heroine actually created by a woman: Miss Fury. Conceived, written and drawn by June Tarpe Mills, Miss Fury began as a Sunday newspaper strip launched for the Bell Syndicate (who also handled Mutt and Jeff, political cartoons by Rube Goldberg and many others). At the time, Mills was a relative comics veteran, having freelanced since 1936 for several comic shops and publishers under her pseudonym of “Tarpe Mills,” creating several characters (Cat Man, The Purple Zombie, Daredevil Barry Finn) and appearing in multiple titles. Author Victoria Ingalls, in an abstract for the American Psychological Association, noted that out of hundreds of superheroines, only eleven were ever created by women not working with male writers, and that June Tarpe Mills’ Miss Fury was chronologically the first.

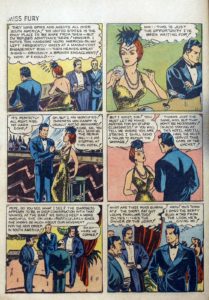

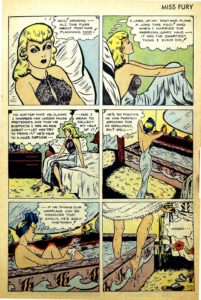

Mills based her art style on Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates), and her character’s features on her own appearance. Miss Fury was in reality wealthy socialite Marla Drake, heavily involved in foreign espionage and who occasionally dressed in a revealing black, skintight catsuit while battling Nazi spies around the globe. It’s a credit to Mills’ strength as an artist, writer and all-around storyteller that the series seldom relied on Marla Drake appearing in costume, but still kept readers engaged in its drama.

Speaking of outfits, the series paid a lot of attention to the characters’ clothing, making sure Marla and her Nazi rival Erica Von Kampf were always drawn in the heights of designer fashion, giving the series a sort-of early James Bond-like international glamour. Bondian parallels also extended to appearances in the strip of lingerie scenes, spike heels, whips, girl-on-girl violence and other fetishistic moments. This sometimes led to Miss Fury running afoul of censors: one bathing scene from 1941 was excised for its comic book reprint, and a bikini sequence in 1947 was considered daring enough that 37 newspapers cancelled the strip for that day.

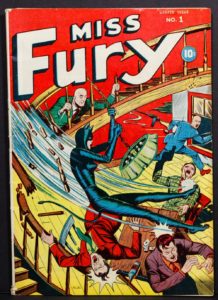

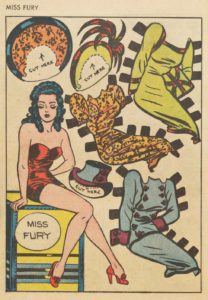

Miss Fury would be reprinted into comic books in 1942, by a company called Timely Comics (later to change their name to Marvel Comics), who’d publish her until 1946. Her newspaper strip ran until 1952, for 351 consecutive weeks with a peak circulation of over 100 papers. She also appeared on the nose of three American warplanes in both Europe and the South Pacific. Sadly, no movies or radio shows would be made from Miss Fury, though in keeping with popular trends, her strip did feature paper dolls of the cast you could cut out and dress in different outfits.

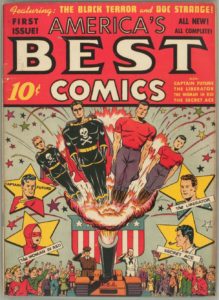

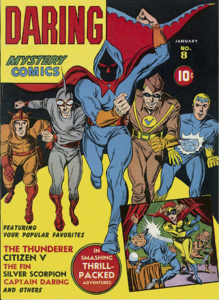

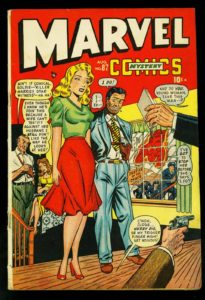

Timely/Marvel, a publisher who emerged from the lower rungs of sleazy adventure, sci-fi and “weird menace” pulps in the thirties, was never one to miss a commercial trend and, when it stumbled upon a successful idea, tended to work (and re-work) it to death. Timely had some luck in 1939 with Marvel Mystery Comics, featuring fire/water superheroes The Human Torch and The Sub-Mariner, then again in 1941 with the uber-patriotic Captain America. Not to be left out of the mystery woman market, in April of 1941 they introduced The Silver Scorpion into the pages of Daring Mystery Comics #7. Created by Harry Sahle, she can be considered Marvel Comics first costumed heroine, long before the parade of Ms. Marvels, Black Widows and She-Hulks they’re currently known for.

Betty Barstow, secretary to P.I. Dan Harley, dons a superhero-style costume for a masquerade ball and on route uses her inevitable jiujitsu and investigative skill to solve a case her employer has turned down. Enjoying it, she continues as a masked crime fighter. Oddly, despite her name, she was never pictured in a silver costume, but yellow and red. She exposed counterfeiters disguised as ghosts, a fake spiritualist and a mad scientist with a viral aging plague before ceasing publication the same year.

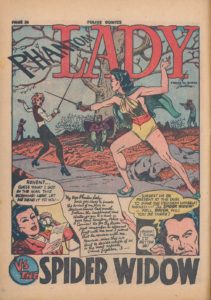

Back at Quality Publications (in more ways than one), The Spider Widow began in June, 1942. Dianne Grayton is another bored and wealthy athlete who’s decided to fight crime and foreign saboteurs… by dressing up as a hag witch, complete with green face paint, putty nose, pointy hat and fright wig. She debuted in Feature Comics #57, created by talented writer/artist Frank Borth, who’d chronicle her adventures until issue #72, and his military draft. Spider Widow would partner with a love-struck flying hero called The Raven, who’d leave his own strip in Quality’s Police Comics to co-star in hers. Her character would then move over to Police Comics, where she’d develop a jealous rivalry over The Raven with the Phantom Lady, leading to feuds, cross-overs and eventual team-ups. Talk about your drama queens.

She was a long way from the worst, however. That distinction would probably go to The Purple Tigress from Fox Publications in 1944. The character was a blonde debutante and spoiled society girl (“Ann Morgan, the richest girl in the city!”) who had 3 boyfriends and only 2 published stories. She fought crime for no discernible reason while wearing a lavender cape and striped bikini.

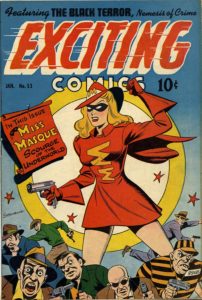

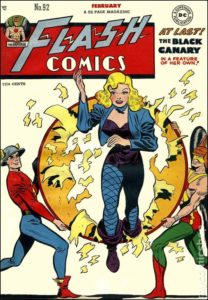

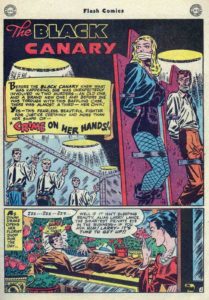

Superhero popularity faded by the end of the war, and publishers tried injecting sex-appeal to keep the genre afloat. Several mysterious heroines came onto the scene, but for the most part these were copies of earlier, more successful models or adjuncts to existing male characters. Miss Masque (1946-49), again from Nedor-Standard Publications, was yet another socialite fighting crime with just a costume, mask and pair of pistols. Over at Harry Donenfeld’s DC, Black Canary (1947) began as a sexy criminal in the strip Johnny Thunder but reformed, took over the series, and then began fighting crime and dating Gotham City detective Larry Lance. DC also introduced Merry the Girl of 1000 Gimmicks, who began as a masked supporting character to the Star-Spangled Kid and Stripesy, lead feature of Star-Spangled Comics, but soon replaced them both.

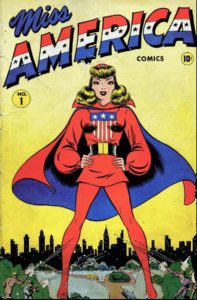

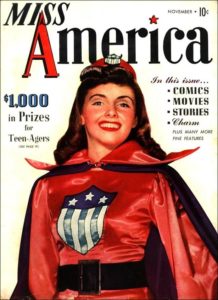

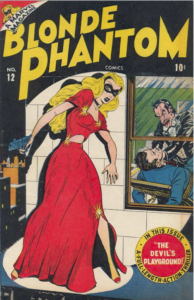

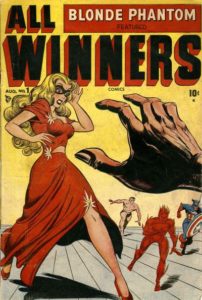

Timely/Marvel Comics’ heroes also begat female contemporaries: Miss America, Timely’s patriotic answer to DC’s superheroine Wonder Woman, ran in her own title from 1943 to 1948 (after Wonder Woman & Sheena Queen of the Jungle, only the third comic book heroine with a solo magazine). It would eventually become a romance comic by decade’s end. Their Blonde Phantom (1946-49) was a Phantom Lady knock-off and yet another secretary to a P.I., this time a detective named Mark Mason. Why all these capable women preferred posing as mousy secretaries for investigators rather than just opening their own agencies is a mystery unto itself. Most male private eyes in comic books had either returned from winning the war or had spent time on the home front successfully battling gangsters, Fifth Columnists and the occasional mad scientist. But they couldn’t recognize the talent right under their noses? Were masculine egos so fragile? It must have been the PTSD…

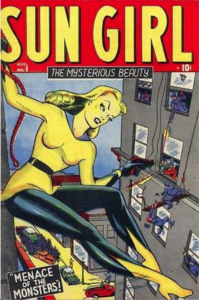

Captain America’s wartime girlfriend Betsy Ross, a supporting player since 1941, was given a post-war bullet-proof cape (to match the Captain’s bullet-proof shield) and became Golden Girl, lasting until 1949. Readers of the undersea hero Namor, the Sub-Mariner were soon introduced to his aquatic cousin Namora in 1947, while Human Torch was soon partnered with Sun Girl (1948), armed with her solar ray gun. The goddess Venus also descended to our world to battle crime at the company in 1948, an early “Gods on Earth” theme that Marvel would perfect by the 1960s with their character Thor. But she, too, would ultimately focus on humorous teen romance tales.

With war’s end, times were changing, as were expectations of women’s roles in society. Perhaps everyone was conditioned for conflict, but revolt was in the air. Conservative forces were now fighting for control in America, and women were beginning to be chastised for showing the very independence our country had asked from them during the war. Women in comics either began to represent “traditional” roles as romance objects, defenders of the domestic status quo, and help-meets for male heroes (Supergirl, Batwoman, et.al.), or they were cast as dangerously sexualized and criminal outliers. Rightfully having none of it, some talented women creators would begin asserting themselves in response.

To Be Continued…