MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. I Wake Up Screaming image copyright 20th Century Fox Studios. Raw Deal pressbook copyright 1948 by Eagle-Lion Classics, a division of United Artists. Tales of Suspense Comics and all related characters are copyright Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Worldwide Inc., a division of The Walt Disney Company. Mr. District Attorney Comics is copyright DC Entertainment, Warner Bros. Global Brands and Franchises division of Warner Bros. Discovery and AT&T’s Warner Media, respectively. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators and studios, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

Though christened after WWII, most film scholars will cite the years 1941 to approximately the mid-1950s as the “classic era” of the American movie genre called film noir, from roughly John Houston’s adaption of Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon and Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane to about Robert Aldrich’s Cold War-tinged Kiss Me Deadly. Interestingly, the “classic era” of crime comic books parallels these years exactly, emerging and vanishing for many of the same reasons.

Crime and mystery in comic books had always followed popular trends from other media, be it variations on newspaper strips like Dick Tracy, pulp fiction pioneered in Black Mask, or the gangster movies of Jimmy Cagney and George Raft. Even superheroes could be seen as an outgrowth of radio mystery men like The Green Hornet or The Shadow and ‘Hero Pulps’ like Doc Savage. So, as film noir began, it was no surprise that comics would start adopting and imitating this new style.

As usual, Will Eisner would be just a little ahead of the curve. In interviews, he often told how after viewing 1941’s Citizen Kane and its sinuous, expressionistic cinematography and editing, his work would begin taking on many of those same dramatic elements. Kane’s rich visuals, in fact, would become an inspiration to many young artists in the industry. Opening at the Palace Theater on May 1, playing NYC for over a year, comic book creators would see it again and again like a new amusement park ride, absorbing its storytelling and techniques.

Soon stories from the Eisner-Iger “shop,” and many others besides, began reflecting more experimental, expressionist moods. No longer content simply imitating newspaper strips, comic book art began maturing into its own visual language. This was as, simultaneously, 1941’s Maltese Falcon, Among the Living, I Wake Up Screaming, Out of the Fog and The Face Behind the Mask began creeping onto movie screens, and 1942’s launch of Lev Gleason’s Crime Does Not Pay made hardboiled gangster tales with moody visuals and violent, fatalistic themes firmly established on the comic book racks. It was a zeitgeist moment in popular culture for the crime genre, where stories, mediums and the audience’s taste were all combining until one couldn’t quite tell what influenced which. And whatever this trend was, it was seriously downbeat, emotionally dark and cynical, a bit more psychologically interpretive, and it was definitely everywhere.

Quiet work by two journeyman comics artists would in many ways encapsulate these new noir sensibilities, in the industry’s post-war years especially. And they’d book-end both the “Golden Age of Crime Comics” and the classic film noir era perfectly, front and back.

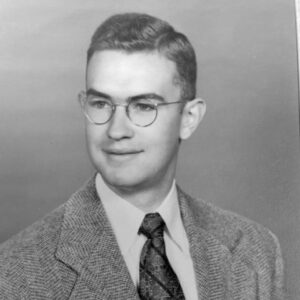

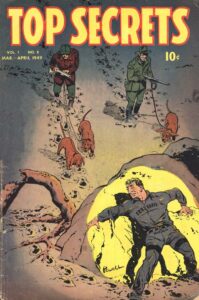

The first was Bob Powell, an illustrator with solid commercial sensibilities and a light, cartoonish touch. Nonetheless he’d summon forth darkness and the surreal, as public taste moved toward more psychologically-driven crime and horror stories in the decade’s latter half. He may never have been the best at it, but he was there for key moments to help usher it all in, perhaps even as much as Will Eisner’s moodier episodes of The Spirit.

A student at the Pratt Institute, Powell began his early career working in the Eisner-Iger shop. Drawing Sheena Queen of the Jungle at Fiction House, Captain America for Timely and Spirit of ’76 for Harvey’s Green Hornet Comics (including issue #10, which featured Mickey Spillane’s Mike Lancer), he’d also co-create the popular series Blackhawk for Quality Publications and provide the back-up feature Mr. Mystic for Will Eisner’s Sunday Spirit Section newspaper inserts.

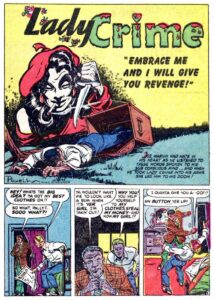

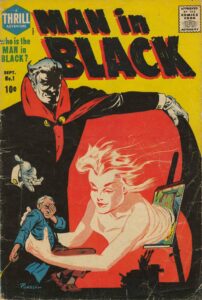

Discharged from the USAF after WWII, he’d freelance on everything: superheroes to westerns, jungle adventure to romance, horror to sci-fi. By 1948, Powell’s input for the expanding True Crime genre would include “Lady Crime” for Harvey’s Kerry Drake Detective comic, a noirish morality tale of a man led astray, and to his doom, by ghostly femme fatale temptation.

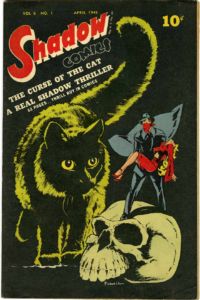

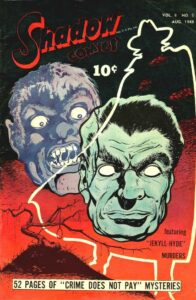

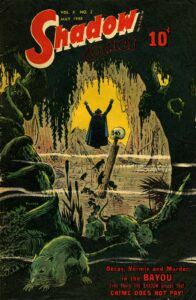

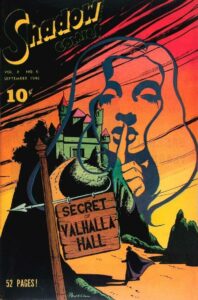

He’d also have an impressive run during this period on Street and Smith’s Shadow Comics, based on the popular radio and pulp character. The Shadow’s pulp adventures could easily best be described as “Agatha Christie puzzle mysteries, if Poirot were replaced by the Phantom of the Opera, and every story ended in a gunfight.” His radio tales were even more mysterioso, with the character able to become psychically invisible as he ghost-busted haunted houses, challenged family curses and thwarted mad scientists.

The comic book version combined approaches from both, and on covers especially Powell rose to the occasion. He’d also draw the entire comic, including back-up features Nick Carter (a long-established detective series since the days of dime novels) and the scientific, globe-trotting pulp adventurer Doc Savage, showing off his versatility. But it was on the lead character that Powell really shined.

He’d couple clean draftsmanship and simple storytelling with dark, horror film atmospherics, plus experimental touches of expressionism and Dali-esque hallucinogenic landscapes. It was visually on-trend with the more surreal noir that crime movies were becoming, such as Robert Siodmak’s evocative Phantom Lady or Welles’ The Lady from Shanghai.

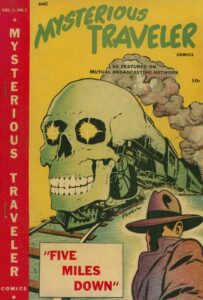

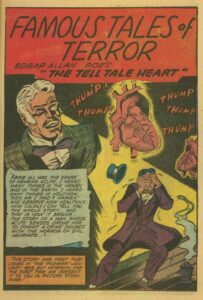

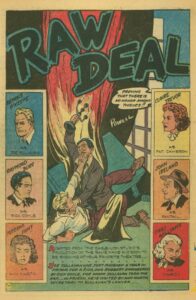

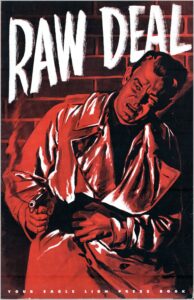

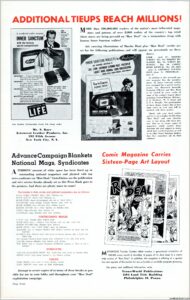

Bob Powell would confront film noir directly in 1948, producing a one-shot comic book based on the radio show The Mysterious Traveler, an anthology suspense series. It featured not only that series’ episode “Five Miles Down,” about a strange encounter beneath the Earth, and Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” (a reprint, not drawn by Powell), but also an adaption of the film Raw Deal, starring Dennis O’Keefe, Raymond Burr and Marsha Hunt, an Eagle-Lion Studios noir “soon to be showing at your favorite theater…” This comic version was even name-checked in the film’s advertising press book (see below). Crime movies were now turning to indie comic books to help their marketing, and Bob Powell was part of it.

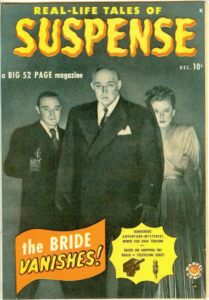

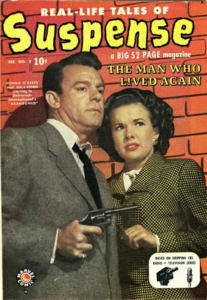

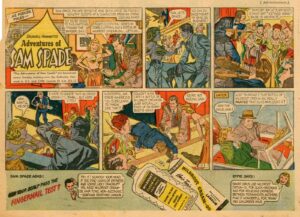

Alongside cinema’s downbeat film noir style, other comic adaptions flourished. By 1949, Timely had a series based on the radio and TV show Suspense. That year, RKO used comic strips to advertise Robert Mitchum’s film The Big Steal. (Of course, radio’s version of Hammett’s Sam Spade had, in fact, advertised with comic strips for sponsor Wildroot Hair Cream even earlier.)

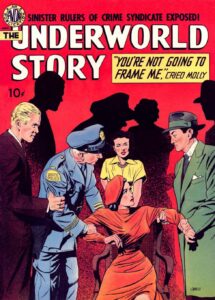

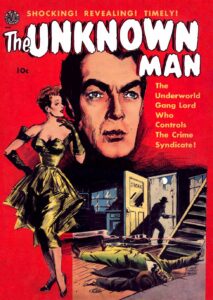

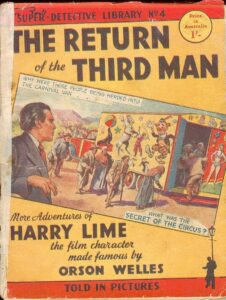

Comic book adaptions of the films The Underworld Story and The Unknown Man issued from Avon Publications, in 1950 and 1951 respectively, and radio’s Martin Kane Private Eye and Mr. District Attorney got their own books from Fox and DC-National. In 1953, Britain’s Super-Detective Library series (the genre was, after all, a global phenomenon) produced The Return of the Third Man, adapted from the Orson Welles’ Adventures of Harry Lime radio series, if you can believe that. By 1954, previously-mentioned Timor Publication’s Crime Detector #5, having used up Mickey Spillane’s pilfered Mike Danger material, could foist an unauthorized adaption of 1950’s Gun Crazy called “Gun Happy.”

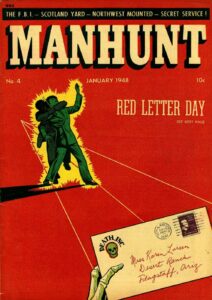

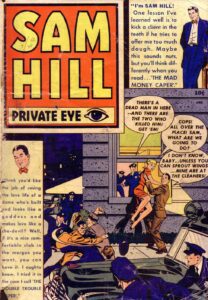

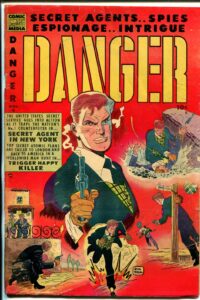

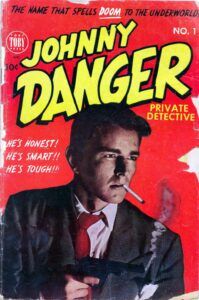

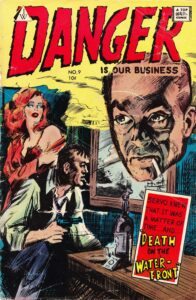

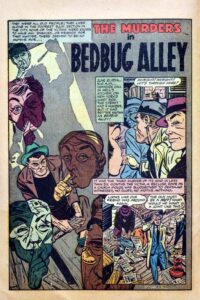

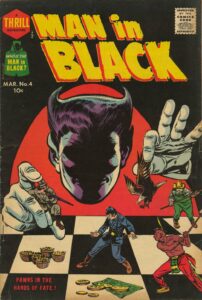

And speaking of Spillane, his brand of mercilessness couldn’t go un-ignored in the comic book realm, not at the numbers his novels were pulling. Hardboiled, fatalistic, testosterone-fueled police detectives, PIs, G-Men, T-Men, he-men secret operatives and their related titles proliferated, including Steve Saunders Special Agent (1947), Ace High in Manhunt (1947-53), Sam Hill Private Eye (1950), Danger (1953), Johnny Danger (1954), Danger Is Our Business (1954), plus a good deal more.

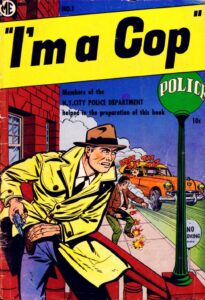

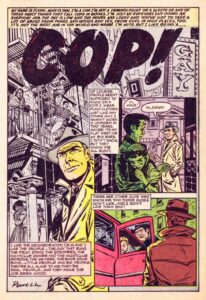

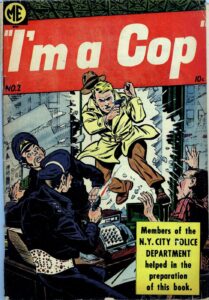

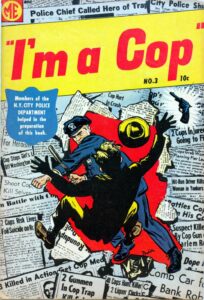

Bob Powell’s finest work in the genre also came in 1954, with a three-issue series from Magazine Enterprises called I’m A Cop. Showcasing gritty, realistic police melodramas drawn against immersive, detailed cityscapes, it reads like a comic book version of Ed McBain’s 57th Precinct novels. It still holds up well even today.

A solid industry pro who always delivered, Powell would become Art Director for the humor magazine Sick, design the legendary Topps Trading Card series Mars Attacks and also work on Marvel’s Daredevil, at DC and for several others before his passing in 1967.

To Be Continued…