MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

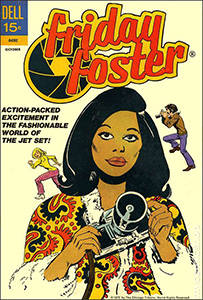

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. All dime novel images are courtesy the Johannsen and LeBlanc Collection from the Rare Book and Special Collections at Northern Illinois University, and its site Nickels and Dimes. The Spirit and its related characters are copyright Will Eisner. Nick Carter, Doc Savage and The Shadow are copyright Conde Nast and associates. Young Allies, Fantastic Four and Black Panther and all related characters are copyright Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Worldwide Inc., a division of The Walt Disney Company. Lobo is copyright Dell Publishing. Friday Foster is copyright the Chicago News Syndicate. All others are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

The impact of slavery, the Civil War, cultural and socio-economic repression and Jim Crow laws had formalized the stereotyping of black Americans in mainstream publishing early on. Yet even in an era of institutionalized racism, and in the face of violent and spiteful Caucasian recidivism, by the early 20th century several black press associations and news agencies existed, representing most parts of the US from coast to coast. By 1940, these various African American newspaper publishers banded together to form what is today known as the National Newspaper Publishers Association. In addition to journalism, championing equality and civil rights in political and business affairs, even serializing pulp-genre fiction (!), they, like any newspaper, also created comics.

Progressive by necessity, for survival, you can bet these didn’t resort to racial stereotyping. The first representation of black characters in comics to be drawn realistically and treated as equals, even capably superior, can be found here. With threads beginning in 1938, in Jackie Ormes’ romance strip Torchy Brown for the Pittsburgh Courier, this trend would continue into adventure series by WWII.

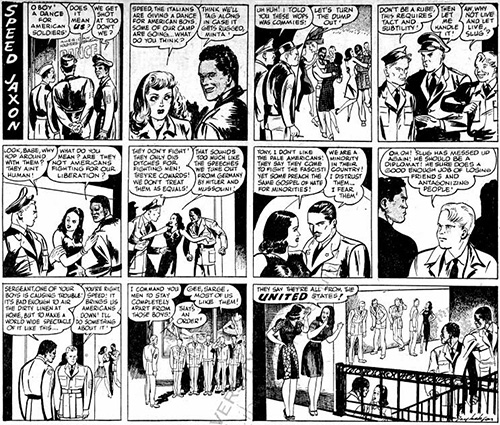

One perfect example was Speed Jaxon, by writer-artist Jay Jackson (under the pen name ‘Pol Churi’), and syndicated in several black newspapers, such as the Chicago Defender, Michigan Chronicle, Louisville Defender, the Tri-State Defender and the New York Age Defender. Speed was a soldier of fortune and US operative battling Nazi spies and saboteurs, even as he dealt with racism from within the ranks of his own nation’s military. The stories often made no bones about equating the two, or warning about its effects on the morale of the country. Able to single-handedly rout an entire German submarine in the open sea, or a nest of fifth columnists on an Army base in Italy, or later, during a mission to Ethiopia, even discover a lost civilization, Speed Jaxon was a superb adventure strip hero in the classic vein.

Jay Jackson, the series creator, began working in the 20s as an editorial and humor cartoonist, joining the staff of the Chicago Defender in 1933. He was an accomplished muralist and fashion illustrator, dabbled in layout and catalogue design, and worked for a number of advertising agencies (most famously, on Murray’s Pomade hair products and for Chicago’s Warner Bros. Theater). He was also the recipient of two “Front Page” Awards from the American Newspaper Guild and a citation by the US Government for his cartoons and posters during WWII bond drives, with his work additionally being distributed by the Office of War Information.

From such series, artists, and publications, the old minstrel-show, pickaninny stereotypes were shattered, and a new reality began to emerge in the American zeitgeist.

Meanwhile, during WWII, labor shortages had seen millions of black Americans joining both industry and the military. And although the US Army did not officially desegregate until after the war, the conflict found many diverse Americans fighting side-by-side as equals against a common enemy, and forced to confront that enemy’s explicitly racist agenda. News of the camps made that point clear.

But after returning to civilian life, the old hatreds began to reassert themselves. There would be, again, push-back on new-found black economic mobility; race riots would soon break out in America as post-war suburbs fought to remain segregated. Yet change, once begun, is hard to stop…and for a brief period of time in the late 1940’s, in the afterglow of victory, equality and respect for basic human rights seemed to flower in comics, as characters of color began to emerge as equals. In one sense, it was just good business. In another, it augured the very beginnings of the end for Jim Crow.

And, lo and behold, crime comics would help communicate that change.

It started as popular creators who had previously relied on broad racial caricature, including such major names as newspaper cartoonists Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates) and Harold Gray (Little Orphan Annie), began working to find new, more realistic approaches to their use of characterization. Will Eisner, always the critical thinker, and perhaps sensing his error, began phasing Ebony White out of The Spirit in 1946, sending the character off to school with only a few guest-starring return visits. (In 1947, Eisner would introduce into one story a non-stereotyped black policeman, Lieutenant Gray, and described in the strip by a white cop as “one of our keenest and most able detectives.”)

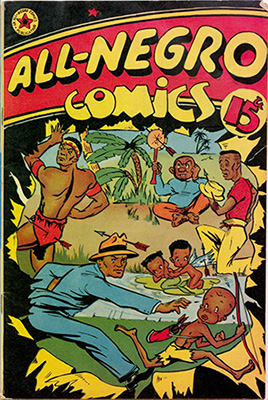

But more importantly, in June 1947 came All-Negro Comics #1, featuring all original material by black creators, and published in Philadelphia by Orrin C. Evans, a long-time Afro-American newspaperman. He was contributor to the official paper of the NAACP, The Crisis, and the first black journalist in the US to cover general assignments for a mainstream white paper, the Philadelphia Record. When that paper shuttered in 1947, Evans launched the comic book to create, in his words, “another milestone in the splendid history of negro journalism.”

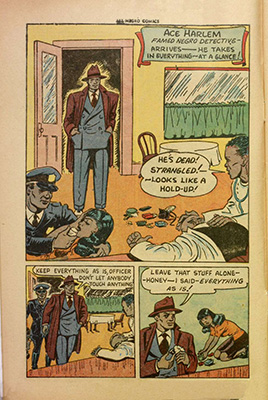

All-Negro Comics’ lead feature was Ace Harlem, a canny, no-nonsense police detective by artist and writer John Terrel, hot on the trail of a pair of zoot-suited, hep-cat murderers, and admonishing readers to “Remember – Crime doesn’t pay, kids! Stick to the church, and use up your energy in good, clean sports.” Smooth, with his trench coat and snap-brimmed hat, stepping straight from the hardboiled school, Ace Harlem stood as iconic and impressive as any Bogart PI from the movies.

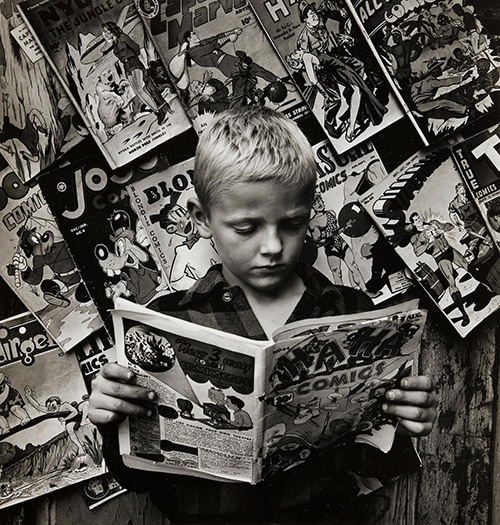

A short, two-page text story in that issue also included a crime theme, with two young children outwitting a dangerous bootlegger in the swamps of Alabama. Plus, there was the series Lion Man, a black jungle hero sent to the African Gold Coast by the U.N. to prevent foreign agents from stealing uranium. There were also humor strips that were clever, wide-ranging, and stereotyped no one. It was a pioneering comic book that fit in perfectly on the newsstands of the era (see photo below, upper right).

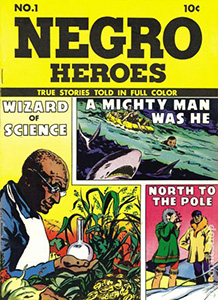

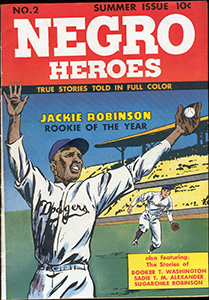

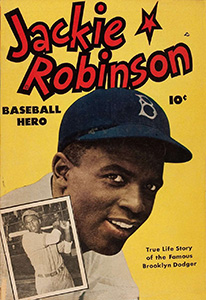

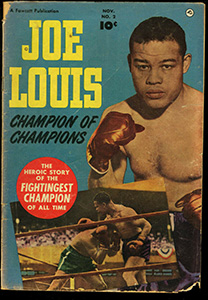

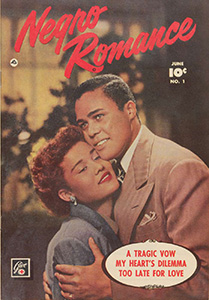

Sadly, a second issue was prepared but did not see print. Orrin Evans was unable to secure the newsprint paper he needed to publish it, nor find vendors to carry it. Some writers have come to believe he was blocked by prejudiced distributors working with competing white publishers, who themselves were planning to produce their own black-themed titles. True or not, soon thereafter The Parents’ Institute, publishers of True Comics and the inspirationally-minded Parents’ Magazine, would produce two issues of Negro Heroes in 1947 and 1948, featuring no less than poet Langston Hughes and popular entertainer Danny Kaye as “Advisory Editors.” Then Fawcett Publications, chasing what was estimated to be a $15 million-a-year market, began issuing Jackie Robinson Baseball Hero, Joe Louis Champion of Champions, and the love comic Negro Romances in 1949 and 1950.

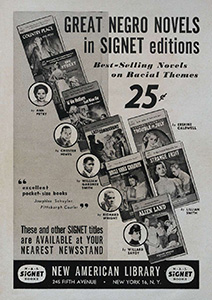

These would each feature images of black Americans as conservative, unthreatening, positive role models, without a whiff of crime or controversy. They were ‘safe’ images, and about as edgy an inroad into the new marketplace as most mainstream publishers would dare. Comics were coming under attack during this period for their supposed influence on juvenile delinquency, crime comics especially, so the very concept of an Ace Harlem -a black man with a badge and a gun- was probably too much to contemplate. (Ironically, Signet’s New American Library pocket book line began issuing paperbacks at the same time by edgier black writers such as Chester Himes, Richard Wright and Ann Petrie. Fawcett would advertise these in the pages of their comic books.)

None of these new comics would last beyond a few issues. In fact, we’re lucky to have had any such titles at all. In the late forties through the fifties, most comic book publishers responded to conservative pressure by simply purging their books of problematic material. This also meant losing adult readership, who soon drifted to paperbacks and magazines. Thus, comic book marketing now aimed more toward kids and young adults.

Controversial and challenging themes, such as race, simply vanished along with crime, sexuality, violence, drugs and other social transgressions. Bad behavior brought swift justice. ‘Decency’ was the watchword. Only the most positive and patriotic of images were tolerated, along with idealized views of the country’s past, present and future. No criminals or communists, no poor or racially marginalized. Just don’t show it. We had won the war, we were now the best, and the country was on the move!

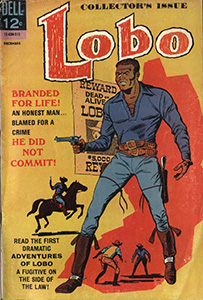

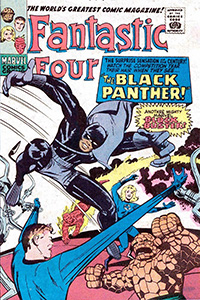

This attitude lasted for most of the 1950s, and into the sixties, but the genie really couldn’t be put back into the bottle. Within a generation, reality and critical thought would creep back into the medium, and soon comic books would begin showing black, Asian, Hispanic and indigenous characters in expansive, powerful and exciting new lights. It was inevitable. And clearly America’s history.

No two would take the same path, or reach any level of popular acceptance in exactly the same way. Native and Hispanic culture, for instance, found some early appreciation, even romanticization, and carried their own solo comic titles; the many diverse Asian societies would be villainized and given atrocious yellow coloring and pidgin dialogue well into the 1980s. And as this diversity in America was recognized, all would endure phases of “exoticization,” objectification by another name and perhaps only by degrees more positive. Change and acceptance was slow. But it still came. We began to see the similarities across humanity, what was familiar amongst all people, despite any sort of outside differences.

Today black creators, indeed creators of every color, from every nation and every gender, are found throughout the comic book industry. They are part of every traditional genre, crime and mystery included. They are no longer the exception. It isn’t even a question. And that’s as it should be.

But the struggle has been long, and still continues. Recently, as reactionary politics once again raise the specters of separatism, the question becomes one of interpretation. Looking back over the history of misrepresentation in the medium, knowing the many years of suppressed talent and overt racism, what are we to make of the images we see? How do we place those derisive images from our past into a proper context?

For the modern writer of crime and mystery fiction, asking themselves how best to deal with questions of race, maybe the answer lies closer to what historian John Lukacs describes in his book Historical Consciousness: “Historical understanding transcends both antiquarianism (looking at the past for its own sake) and presentism (applying the standards of the present to the past). Rather, historical understanding involves an imaginative engagement with the past that tries to deepen our understanding of the choices people in the past faced.”

The easy response is to say “Well, it was a different time.” Well, yes.

But if said, perhaps we should also then objectively ask ourselves: when is it acceptable, at any time, to be White Supremacist?

To Be Continued…