MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. New Fun Comics and Superman are copyright DC Entertainment, Warner Bros. Global Brands and Franchises division of Warner Bros., and AT&T’s Warner Media, respectively. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators, unless otherwise noted.)

WARNING: Contains explicit imagery.

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

At the juncture of publishing and race, art and commerce, America’s North and South, the red threads of our Evidence Board connect us to one of the early black creators, his relationship to a pornographer with gangland connections, and a tale that involves pulp fiction, true crime, and the very origins of America’s comic book industry. That creator’s name was Al Barreaux, and his story is pretty remarkable.

Born in racially segregated Charleston, South Carolina in 1899, Adolphe Leslie Barreaux grew up in the state during a time when lynch mobs were commonplace and entire black townships were burned to the ground. Light enough to pass for white, he learned to do so whenever it suited him, or presented an advantage. He also suffered an early, near-fatal bout with typhoid in 1915, and during his long, lonely years of recovery, he’d entertain himself by learning to read and draw.

He was afterward sent to live with aunts in New York City, on the advice of a doctor who felt “a more vigorous climate” would speed his recovery. Graduating high school there in 1919, he attended the Yale School of Art in 1920, majoring in Elizabethan English and fine arts, joining the fencing team and directing social events. He also sold his first short story to the pulp magazine Breezy Stories in his freshman year.

After his summer vacation in 1922, Barreaux did not return to Yale, but headed instead to New York City to seek his fortune as a commercial artist. On arrival, he threw himself fully into the height of the Jazz Age, including becoming a member of the famous Bohemian Kit-Kat Club. There, he joined art legends like James Montgomery Flagg and Rube Goldberg for their Annual Artists & Models Ball, performing comedy skits alongside their nude models. In 1923, the Ball was raided by the vice squad for indecency, and the scandal generated such publicity that the Ball of 1924 sold thousands of tickets and had to be staged at the enormous Lyceum Theater on Broadway and Times Square, home of Ziegfeld’s Follies.

During Prohibition, popular culture was influenced significantly by such risqué productions, and many side industries blossomed, including the sales of the ‘spicy’ pulps, which were often purchased as souvenirs by audiences after a naughty night on Broadway. These included such titles as Snappy Stories, Hot Stuff, La Boheme, Artists & Models and Art Lovers. Some included nude photography along with their illustrations.

Al Barreaux joined the ranks of artists who contributed to these racy magazines, then starting in 1924, opened his own series of art studios where he painted celebrity portraits and entertained professionals from the arts, music and theater scene. In 1925, he appeared on Broadway in the musical “Dancing Mothers,” and even had a few bit parts in some early films, where he met stars such as Adolphe Menjou. Throughout the Roaring 20s, young Adolphe kept in demand by regularly supplying columnists with show-biz gossip, jokes, essay articles on feminine beauty, and doing advertising art to pay the bills.

The economic collapse of 1929, and the following Great Depression, hit the advertising industry hard, drying up business. Pulp magazines, however, a popular entertainment that sold cheaply at newsstands and didn’t rely on subscriptions or advertising, were enjoying their greatest period of success. Al shifted to pulp illustration, opening and closing a clutch of studios over the next few years. In 1933, Barreaux fell in with printer, publisher and distributor Harry Donenfeld, a shady producer of racing forms, pulps and Hollywood fan magazines…also tabloids, porn, real estate investments, a suspiciously long string of bankrupted printing and distribution companies, plus a friendly relationship with New York mobster Frank Costello (of the Lucky Luciano crime family (and real-life inspiration for Don Vito Corleone in The Godfather).

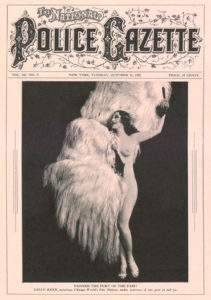

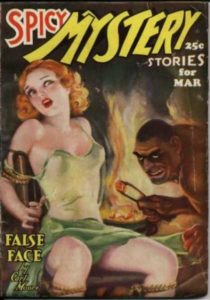

Harry Donenfeld specialized in using his connections in the printing and distribution industries, and maybe his underworld juice as well, to foreclose on debt-ridden publishers and seize their titles. He had recently purchased the weekly publication The National Police Gazette, where Al Barreaux had created a comic strip about a saucy chorus girl named “Flossie Flip.” The Gazette was sold off again after a year, but Barreaux stayed on to serve as the creative art director for Donenfeld Magazines, which included such sexy, ‘under the counter’ pulps as Snappy Stories, Pep, Ginger, Spicy Adventure, Spicy Detective and Spicy Mystery.

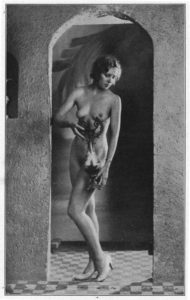

In 1934, an issue of Pep printed an “art photo” of a nude model (above), and ran afoul of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. The slippery Donenfeld fought back but was prosecuted for obscenity. He beat the charge by finding a clerk in the accounting department to personally confess to inserting the offensive image into the magazine, testify he’d done it without his employer’s knowledge, and to do the jail time. After the trial Harry had his name removed from everything but his most wholesome-appearing publications and moved the company’s headquarters (on paper) to Delaware, outside New York’s jurisdiction. He then moved his printing presses to Hell’s Kitchen in Midtown, and carried on business as usual.

To keep up with demand for illustrations, and instead of working for Harry on a straight salary, in 1934 Al Barreaux opted to form Majestic Studio, an independent artist’s agency. There he managed several painters and illustrators, and coordinated production for all the pen-and-ink artwork that appeared in Donenfeld’s expanding line of magazines. No one knew it at the time, but Adolphe Barreaux had just created the first comic book “shop.” It became the model for later industry packaging studios by folks like Harry “A” Chesler and the Will Eisner & Jerry Iger shop.

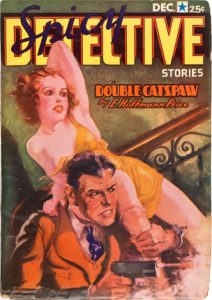

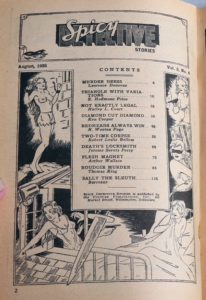

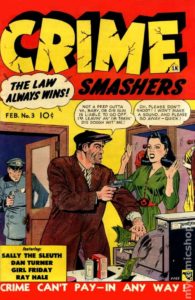

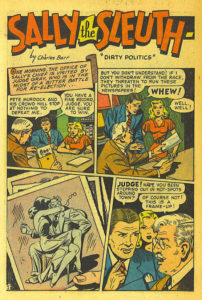

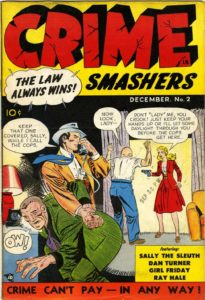

That same year, Barreaux convinced Harry Donenfeld to publish an eight-page erotic comic strip called Sally the Sleuth in the November 1934 issue of Spicy Detective Stories. It was drawn fast and crude, and wasn’t really all that erotic, but Sally did drop her clothes during the course of solving all her cases, and the idea of an adult comic strip proved innovative and commercial, especially in the popular genre of ‘hardboiled’ crime fiction. Soon Donenfeld’s other titles began featuring comics, such as sexy explorer Diana Daw in Spicy Adventure, Polly of the Plains in Spicy Western and, as we’ve mentioned elsewhere, Dan Turner comics for Hollywood Detective. All were mostly written and drawn by Al Barreaux, and ran for decades.

Soon, Al’s Majestic Studios was creating strips for others. A few weren’t even “erotic,” but made for straight-up humor, western, science fiction and adventure pulps, many of whom were business partners of Donenfeld. That obscenity trial had been a close call for Harry, and he’d began casting around for a safer publishing field to get involved with. He found it in the new medium of comic books.

Detective Dan had created the first all-original, dramatic, single themed comic book title in 1933 (a hardboiled crime story, which featured stereotyped black porters, btw). Just two years later, in February 1935, the very first omnibus comic book of all-original material (no reprints from the newspapers!) would hit the stands. Entitled New Fun Comics #1, it was published by National Allied Periodicals and its partner, the Nicholson Publishing Company, with printing and distribution assistance from Harry Donenfeld.

Al Barreaux’s Majestic Studios agency supplied all the strips that filled its pages, and Al’s series, The Magic Crystal of History, was right inside on page one. New Fun Comics would soon change its name to More Fun Comics, and Donenfeld would quietly become an influential partner with National Allied.

In 1937, Donenfeld negotiated a contract to publish the popular radio character The Lone Ranger in his own magazine, forming yet another company, Trojan Publishing Corp., to do it. Then, teaming with friends at the National Allied Newspaper Syndicate, he orchestrated an enforced bankruptcy on Nicholson Publishing over an outstanding debt of $63,380.

Meanwhile, in August of that year, over in the pages of Spicy Mystery, Al Barreaux introduced a sci-fi fantasy strip called The Astounding Adventures of Olga Mesmer, the Girl with the X-Ray Eyes. Olga was the daughter of a mad scientist and a woman from Venus, whose mixed heritage gave her “superhuman strength and the ability to see right through solid objects.” Olga, unique as she was, still lost her clothes during her adventures as fast as any other heroine in a “Spicy” strip, and would cease publication the very next year. But in the meantime, ten months before anybody else, Al Barreaux’s shop had produced and created the very first super-powered character in comics.

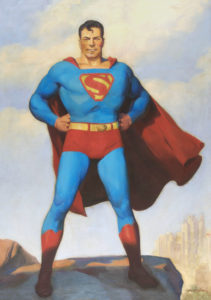

Then, in June 1938, an ailing National Allied published Action Comics #1, featuring a character called Superman, which became comic books’ first major bestseller and would soon move millions of copies a month. By December, Harry Donenfeld and his associate Jack Liebowitz quickly forced a buyout of National’s partner Nicholson Publishing over its bankruptcy debts, and in the process gained control over National Allied Publications and all its properties. Donenfeld became CEO and Liebowitz became the publisher. In 1939, their company scored another big hit in issue #27 of their Detective Comics title, with a character called The Batman. National Allied soon changed its name to DC-National, and Harry—now in possession of both Superman and Batman—began to get rich beyond his wildest dreams.

Donenfeld promptly housed Al Barreaux’s Majestic Studios in his personal company headquarters on Lexington Ave., a massive building complex near Grand Central Station that included the Chrysler Building, the Commodore Hotel, and the Waldorf-Astoria. The Waldorf had a barber shop downstairs, and every week Harry and Frank Costello would spend a day there discussing business together, sitting side by side in barber chairs. When the barber’s son wanted a career in art, as an extra bonus, Harry got the kid steady work up at Al’s studio, painting covers for the ‘Spicy’ pulps.

The explosion in Superman’s sales had created a demand for comic books and superhero characters. Batman fed it. The industry was suddenly on the map, and growing. So of course, in 1939, Harry Donenfeld formed the Publishers Distribution Corporation, and began extending operating credit to ambitious, small-time, entry-level comic book publishers everywhere. Soon, Donenfeld—in addition to owning DC comics—had a profitable stake in distributing a large portion of the entire fledgling comic book industry. Harry then forwarded Al Barreaux’s artists plenty of outside work, in addition to filling his own growing comic book division and pulp publications.

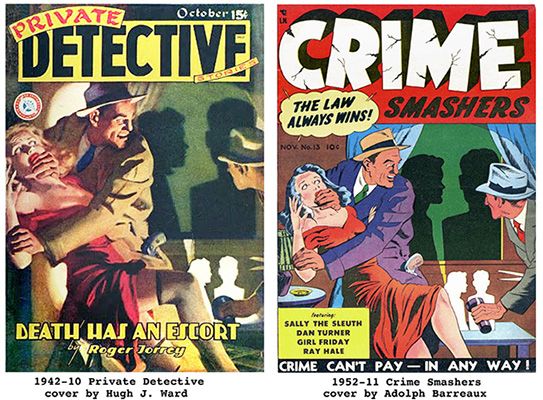

In 1940, Donenfeld marketed Superman to his contacts in radio, and used Robert Maxwell Joffe, his top author of risqué stories from Pep, La Paree and Spicy Adventure, to write the scripts and even create the iconic theme music. He commissioned Hugh J. Ward, his top cover painter from the ‘Spicy’ line, to paint an official, life-sized portrait of Superman, which he then had installed over his desk in the DC offices, and where it hung for the rest of his career and for decades after. He’d continue to license Superman toys, games and books, foods, cartoons, films and television shows for decades, helping to create the very comic book mass-marketing playbook that continues to this day.

And that was how a pornographer with underworld ties became the owner of Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman and many others, and one of the biggest comic book entertainment companies in the world. A wealthy and powerful corporate CEO, set for life, who would die decades later at the age of 71, living in a mansion in Riverdale, NY. Frank Costello visited him up to the end.

That clerk from accounting, who went to jail for Harry? He was a model prisoner, earned early release for good behavior, and was rewarded with a permanent job for the rest of his life. For the next thirty years, well into the late 1960s, the staff of DC comics never understood exactly what the little man who went to his own private desk every day, just read the newspaper, then clocked out at the end of the day to quietly go home, was ever actually paid to do.

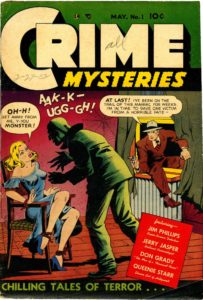

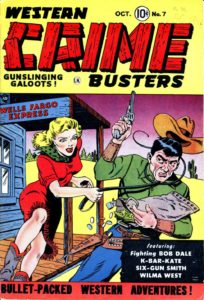

And Al Barreaux? His Majestic Studios continued providing artists and stories for multiple comics and pulp magazines throughout the 1940s. He also found time to illustrate several children’s books. When crime comics, spurred by the success of Lev Gleason’s Crime Does Not Pay, became the rage after WWII and into the next decade, Al was there. And he brought Sally the Sleuth and Dan Turner with him.

Demand for material was high, and occasionally, to meet deadline demands, he’d re-draw old pulp cover paintings to serve as comic book covers. In 1949, in addition to receiving a promotion to editor of the Dan Turner Hollywood Detective pulp, Al also became Editor-In-Chief of Trojan Magazines, and co-owner of Trojan Comics with Donenfeld in 1950.

But by this time, public outcry over the violent and salacious content of comic books was growing. Fueled by the post-war recession, concerns over juvenile delinquency and a perceived rise in the national crime rates had begun to manifest in a strong conservative backlash by PTA, religious groups and even the US Senate in the late forties. Comic books, and crime comics in particular, came into the cross-hairs for their “corrupting influence on children,” along with war, horror and other genre comics featuring grown-up content. Public book burnings, with comic books specifically photographed being thrown in heaps onto bonfires, made newspaper front pages. (Sound familiar?)

By 1952, Trojan Comics declared bankruptcy, in keeping with Harry Donenfeld’s traditional pattern of doing business, and was gone entirely by 1955. In 1953, after the industry adopted the self-censoring Comic Book Code of Decency in response to public concerns and began sanitizing any violent, sexy or adult content, the market collapsed and Al Barreaux shuttered Majestic Studios. Its stable of artists by this time had included such future notables as Wally Wood, Joe Kubert and Frank Frazetta, as well as established crime writer Robert Leslie Bellem.

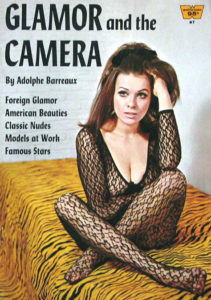

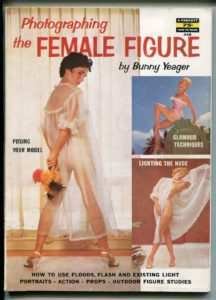

Having found financial success over the years, Barreaux spent time travelling the world, getting to know London, Rome and Paris quite well. Al also made a hobby of archaeology and became quite an expert on the Maya people of Guatemala. By the late 1950s and well into the sixties, he became an editor for the Special Interest Books Division of Fawcett Publications, and edited books for the company on artistic nude photography (including Beauty and the Camera, Salon Photography, Bunny Yeager’s Nudes and Glamor and the Camera), as well as several medical textbooks. Early models he worked with included future actress Julie Newmar. Al Barreaux retired in the 1970s to his home on Riverside Drive in NYC, and died in 1985, at the age of eighty-six.

He’d been a part of New York’s glittering Broadway scene in the Roaring 20s. In the 1930s, he contributed to the heyday of the pulps, pioneered adult comics, then comic-producing “shops,” then created the very first super-powered comic character. He’d help launch the American comic book industry (and the DC company specifically, by filling their first book), formalize and expand both the pulp and comic book mediums through the next decade and a half, and then the “glamour photography” field after that. And always while coping with and overcoming any inherent conflicts in his chosen career path.

Coming from a time and place where being a black man wasn’t thought to matter, he proved it didn’t. Instead, he proved that being a creative, resourceful and talented artist did.

To Be Continued…