MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only and constitute fair use. Detective Comics and all related characters are copyright DC Entertainment, Warner Bros. Global Brands and Franchises division of Warner Bros. Discovery and AT&T’s Warner Media, respectively. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators and rights holders, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

After WWII, as noir permeated popular culture, writers Patricia Highsmith and Mickey Spillane ascended from comic books into the loftier realm of published novelists. But they were leaving behind a place where traditional crime and mystery authors were already very well established. The genre’s literary canon had, in fact, been a part of comic books since the very first.

Then, as now, authors and their creations were “branded IP”; a publisher could license a well-known character or two for a comic book, then hire a “shop” to supply back-up material on demand in various genres to fill out pages (one cowboy, one comedy/gag strip, a superhero, a detective, a lady reporter, maybe a magician, you get the idea). Et voila! A fast, cheap, middle-brow, disposable magazine with mass market appeal, ready-made. A fledgling comic magnate was now in the game. From the beginning, savvy publishers vied for the most popular brands they could afford, because comic books, like serializing, reprinting, translations, radio or movies, were just another platform for expanding a brand’s profile. And especially after Crime Does Not Pay broke big in the 40s, crime, mystery and all its literary progeny were potentially hot comic book commodities.

And that’s how, from Walpole to Poe to Woolrich, Holmes to Spade to Nancy Drew, some famous names have comic adaptions. Holmes has had several. Some who had them, maybe you’d never expect. So…where to start when covering traditional crime and mystery in comic books? The first series adapted, the earliest author? Chronologically or by comic appearance? Comic strips first or comic books? Let’s try a little of each, and string those red threads.

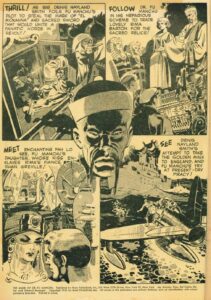

Popular characters (like Nick Carter or The Shadow) had weathered the zeitgeist from dime novels, pulps and radio into funnies, movies and merchandising. But the first major literary mystery figure to cross over into comic books was probably that insidious ol’ Dr. Fu Manchu, author Sax Rohmer’s icon of racist Asian villainy. Headlining multiple novels and short stories from 1913 until 1959, unleashing his diabolical plans across most popular media, the character epitomized both an entire genre and a cliché simultaneously.

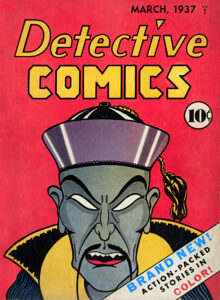

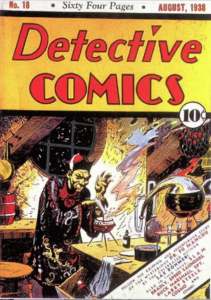

Fu made that big jump into comic books after his first book was adapted into newspaper comic strips from 1931-33, then reprinted in 1938’s Detective Comics #17- #28 by DC-National. Detective Comics just loved Yellow Peril, and sinister Chinese abounded in its stories; even its very first cover spotlighted a knockoff fiendish mastermind called Ching Lung. Appearing a full year before Batman‘s debut in issue #27, DC’s licensing of the original Fu was surely seen as a “get.”

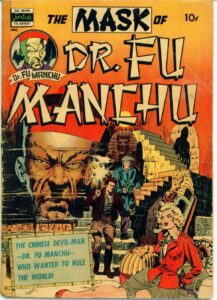

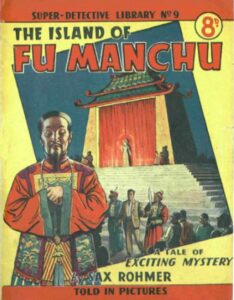

The “Devil Doctor” wouldn’t know his first original comics material until 1951’s one-shot The Mask of Fu Manchu, from Avon Publications, featuring lush artwork (and his best-looking presentation, really) from the legendary Wally Wood. His comic trail went cold until 1959, when Britain’s Fleetwood company adapted Rohmer’s The Island of Fu Manchu in Super Detective Library #9. Then in the 1970s, Marvel Comics licensed the character to be the guest-star/father of Shang-Chi Master of Kung Fu (before their recent movie changed/retro-contextualized him into another Marvel “Yellow Peril” villain, “The Mandarin”). For an ambitious world-conqueror, it represents a slim comic book resume.

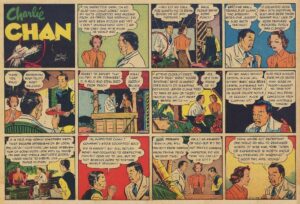

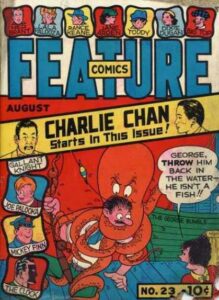

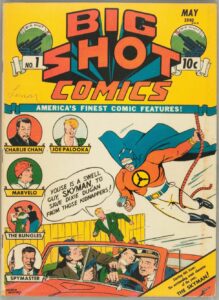

1938 was also the start of a syndicated newspaper strip based on Earl Derr Biggers’ famous Charlie Chan novels. Drawn by Alfred Andriola (later of Dan Dunn and famously, Kerry Drake), it followed the venerable Hawaiian detective as he investigated crime daily, in color on Sundays, until 1942. Boosted by the popular film series, the strip would be picked up and reprinted by 1939, in Quality’s Feature Comics #23-31. He’d seldom be outside a comic book after that. The mining of mystery fiction was now proving potentially lucrative for the comics, and some Big Boys were starting to notice.

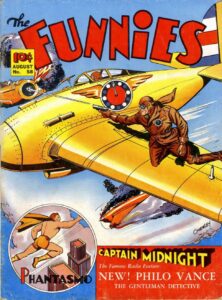

Dell-Western Publishing, for example, was already the largest comic book publisher in America. Western, a printing company with access to a long client list of licensed characters, and Dell, an established publishing firm with solid distribution and marketing history, formed the perfect corporate marriage. They began by making pamphlets reprinting popular newspaper strips in the late 1920s for Sunday supplements and toy store giveaways, years before “comic books” existed. By the mid-1930s they were creating periodicals like The Funnies and Popular Comics to sell reprinted Dick Tracy, Orphan Annie, Mutt & Jeff and Terry & the Pirates strips in a retail magazine format, and the rest is publishing history. To say they’d actually pioneered the comic book wouldn’t be wrong. Having licensing deals with popular authors, newspaper syndicates, radio networks, movie studios and Walt Disney kept them Number One forever.

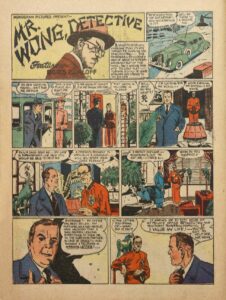

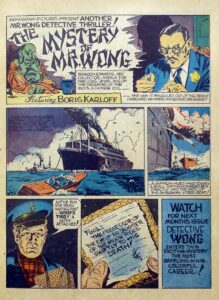

In 1939, Dell-Western’s Popular Comics #38-41, which featured strips based on Zane Gray novels, Edgar Rice Burrough’s Tarzan, Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur, and the Gangbusters radio show, also serialized a comic book adaption of the Monogram Pictures film Mr. Wong, Detective, starring Boris Karloff. Again, in 1940, with issues #43-46, they’d adapt its sequel The Mystery of Mr. Wong. Both movie series and comic book serials came with a literary pedigree: Hugh Wiley’s stories from Colliers Magazine, beginning in 1934, about James Lee Wong, the Chinese American San Francisco Treasury Agent, Yale-educated, 6 feet tall with the “face of a foreign devil — a Yankee.”

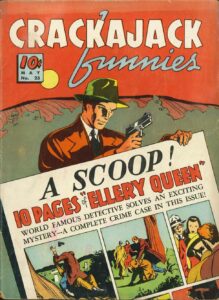

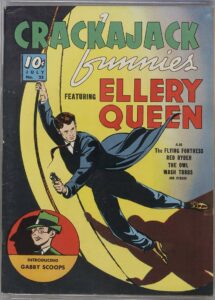

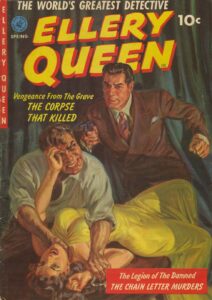

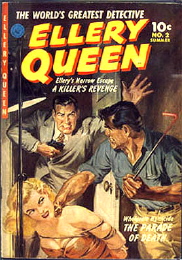

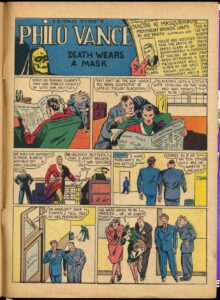

Dell-Western followed up in 1940 by introducing Ellery Queen into their Crackajack Funnies with adaptions of his short stories in issues #23-42. As in the books, the authorship was credited to “Ellery Queen,” but was actually created starting in 1929 by cousins/joint pseudonym Fred Dannay & Manfred Bennington Lee. Inspired by the popular 1919 gentleman-sleuth Philo Vance by S. S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen became the most well-known fictional detective/crime author (take your pick) of the 1930s-40s, including additional comic book series in 1947 and 1949, with a longer career in other media.

Following the success of 1942’s Crime Does Not Pay, but still wanting to keep it classy, Dell soon just began featuring Philo Vance directly. The “man of unusual culture and brilliance…aristocrat by birth and instinct,” ran in The Funnies from issues #56-63. And speaking of class, ‘42 was also the year that Classics Illustrated got into the mystery game.

Classics Illustrated was created in 1941 by Russian-born publisher Albert Lewis Kanter, who believed he could use the new comic book medium to introduce young, reluctant readers to great literature. Starting with Dumas’s The Three Musketeers in issue #1, the series adapted famous, usually public domain, literary novels for over thirty years, including many reprints and re-issues from other companies. Over that time, its list of contributing artists would read like a Who’s Who of industry greats, including Matt Baker, Reed Crandall, Graham Ingels, Everett Raymond Kinstler, Jack Kirby, Al Williamson and a long list of others, like a beacon and magnet for class. Distributed as an educational tool in US and British schools and licensed internationally beginning in 1951, it would indeed expose many children to some very great books. (Original copies still go for top dollar on the collector’s market).

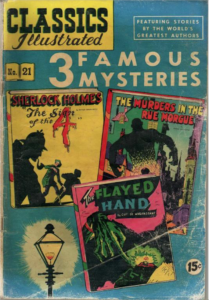

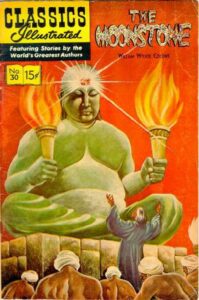

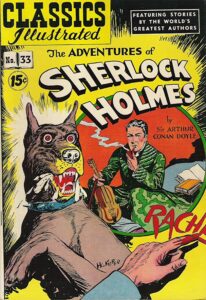

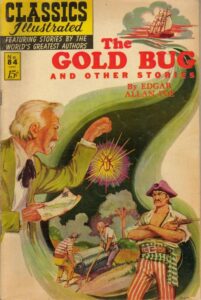

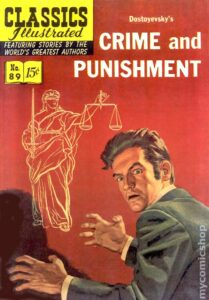

Back in ’42 however, Classics went straight for the throat with issue #21’s Three Famous Mysteries, featuring adaptions of Conan Doyle’s The Sign of Four, Edgar Allan Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue, and Guy de Maupassant’s The Flayed Hand, rendered in all their rough, bloody, pulpy glory. This was easily the earliest legit Sherlock Holmes appearance in comics, certainly a debut for de Maupassant; it would also introduce Poe into comic books for the first time. Later Classics Illustrated covered Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone (#30), The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (#33, The Hound of the Baskervilles included), Poe’s The Gold Bug and Other Stories (#84) and even Dostoyevsky’s Crime & Punishment (#89).

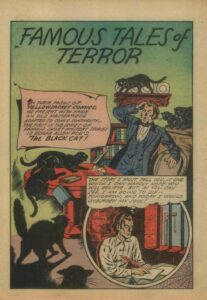

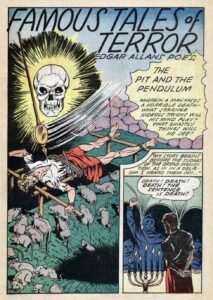

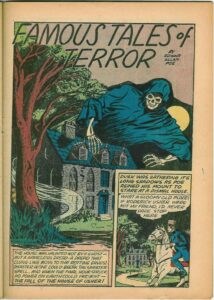

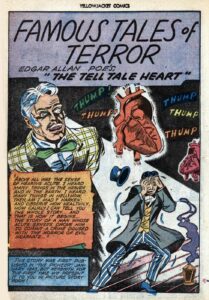

By 1944, Poe had returned with The Black Cat, Pit and the Pendulum, Fall of the House of Usher, and The Tell-Tale Heart in as many issues of Charlton Publication’s Yellowjacket Comics. He’d soon become a fixture in horror/crime titles throughout the 40s, blending in perfectly with the noir era and beyond. Other classic horror and mystery authors would also be added or rediscovered (including Stoker, Kipling, Stevenson and a short adaption of Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto), even as traditional crime and suspense began returning to comics post-WWII.

But this time with a darker, more graphic view…

To Be Continued…