MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. All-True Crime, Justice, Suspense, Men’s Adventure (‘The Torture Master’) and all related characters are copyright Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Worldwide Inc., a division of The Walt Disney Company. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective publishers and creators, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

[WARNING: Contains graphic imagery.]

We’ve talked about crime and horror comics, genre spirit-cousins since the pulp magazine days of “Weird Menace,” coming under extreme criticism and eventual censorship by the 1950s. We’ve mentioned this led to collapse within those genres, and the entire comic book industry, at that time. But how exactly? What started this, why did it occur and who was responsible?

Perhaps even more importantly: how did it come to make patriotic American citizens engage in Nazi Party-style book burnings? Or make comic books themselves actually considered a criminal threat?

In the 1940s the average American consumed one to three comic books a week, purchasing more than a billion comic books in 1942 alone. Read widely by adults as well as children, they’d rack up an average 60 million units sold a month during the latter half of the decade. Almost from inception, the format’s popularity spread throughout the world yet remained primarily a US innovation. Nothing could be considered more American. Then, after WWII, this attitude abruptly changed. So, what went wrong?

To find answers, the threads on our Evidence Board must stretch far, far back…to social movements from even before the 20th century that created the comic book. And to uncomfortable trends in our nation’s own political landscape, even now.

To start, let me suggest that crime comics of the late 1940s and early 1950s, as both disposable entertainment and a social weathervane, weren’t the actual cause for this upheaval. But they were the perfect scapegoat; low-hanging fruit in a time of culture war.

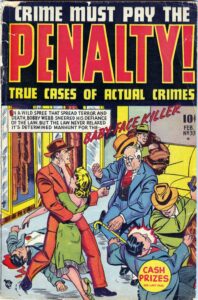

As one comics historian put it: “Crime comics would launch a publishing trend that would last for over for a decade, generate a national discussion, and change the public perception of comic books. Following the war, the constant reminder that the problem of crime still existed (and was commercially popular!) made folks uncomfortable, and there was push-back. Having cleaned up America’s enemies overseas, some factions now wanted to clean up America’s perceived enemies at home. For them, it was time to re-establish some sort of morality.”

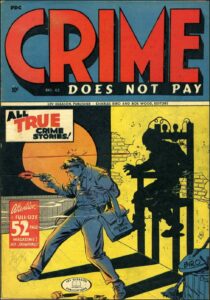

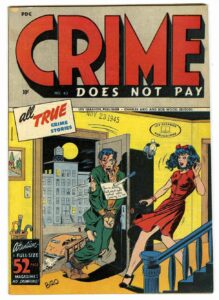

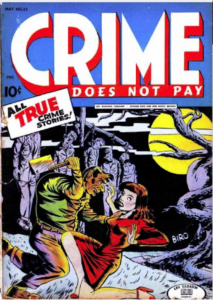

Not that a few couldn’t have used some cleaning up. There was only one Crime Does Not Pay, after all. Violent as it was, publisher Lev Gleason sincerely believed in his comic’s educational, anti-crime message.

Lev was a patriotic military veteran who, following Pearl Harbor, re-enlisted in the US Army and served in uniform until an honorable discharge in 1942. He was also an avowed Leftist, an actual registered Communist Party member in the 1930s (dropping out in protest over the party’s support of the Hitler-Stalin Pact), a vocal defender of Soviet policies in the 1940s and executive board member of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, created to aid those fleeing Franco during the Spanish Civil War.

Additionally, his company was somewhat more racially diverse than others, hiring not only African-Americans but several Japanese-Americans including artists Bob Fujitani, Fred Kida and letterer Ben Oda. Lev, a student of Andover, Harvard, and the Sorbonne, openly wore his politics on his sleeve. (Artist Pete Morisi, who worked for Gleason, was quoted as saying “Everybody knew he was a Commie.”)

Fined with contempt of Congress in 1946 for refusing to turn over Refugee Committee documents to HUAC, he was investigated by the FBI for years, its agents reading his mail, monitoring his phone calls, and going through his trash. When the Bureau finally approached him directly in 1953, Lev talked only about his own past in the party. The only names he’d give were already in the public record. Lev Gleason lived by his principles.

Still, reflecting wartime changes in popular taste, Crime Does Not Pay had begun drifting away from its early cartoonish art style in favor of darker, more realistic scripts and illustration, improvements which increased its sales figures. Lacking the social reform vision of Lev Gleason, or the art and writing chops of Charles Biro and Bob Wood, any genre rivals could only compete by adding more sleaze and sensational content.

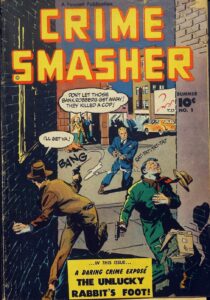

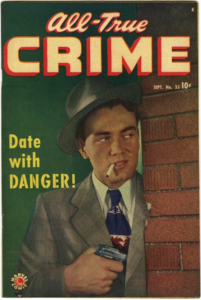

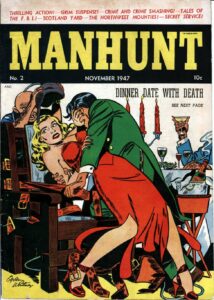

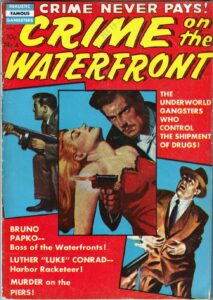

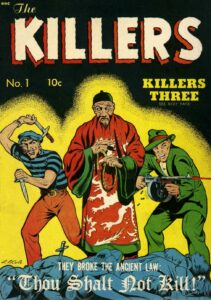

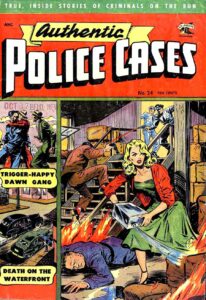

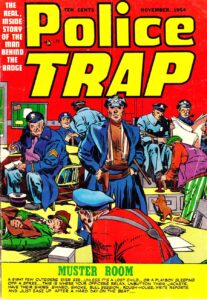

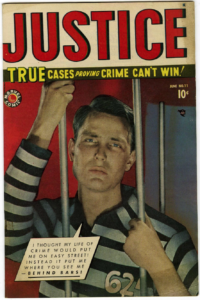

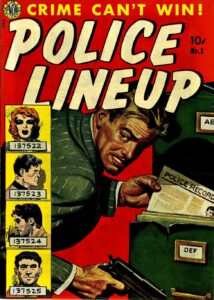

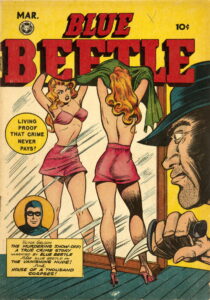

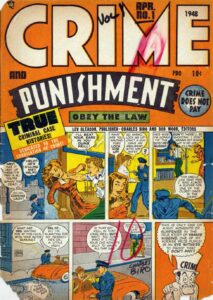

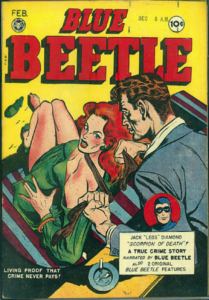

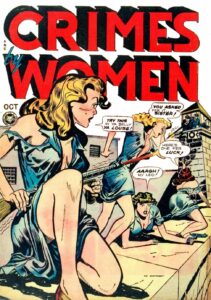

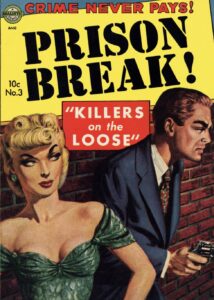

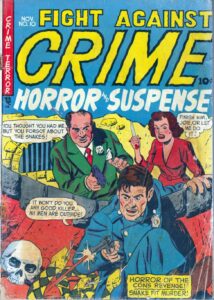

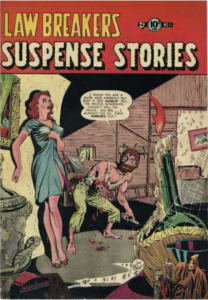

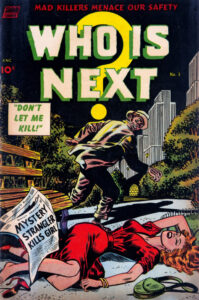

After the war, and an easing of paper restrictions, more comic book companies came on the scene. And as Crime Does Not Pay post-war sales figures creeped into the multi-million copy stratosphere, other publishers felt compelled to expand their lines with a similar comic, and increasingly bloodthirsty results. The True Crime trend even seeped into the remaining superhero titles. To stay ahead, Gleason added a second book, Crime and Punishment, while Crime Does Not Pay boosted its levels of violence and lurid themes. Monthly readership increased, other companies responded accordingly, and the race was on.

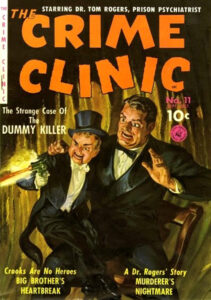

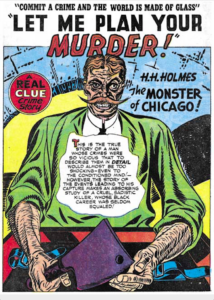

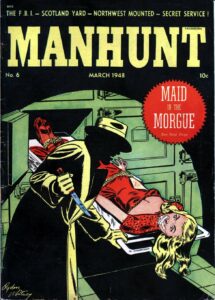

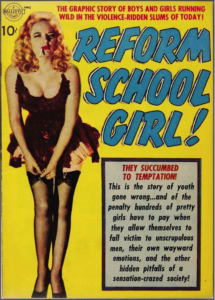

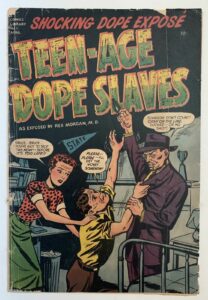

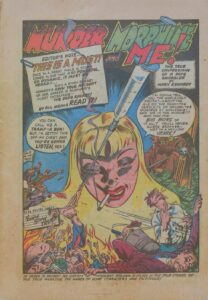

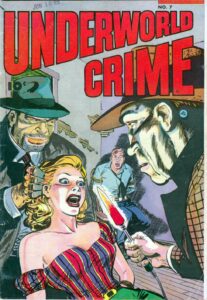

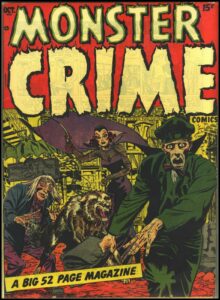

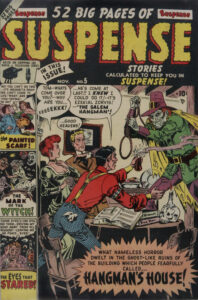

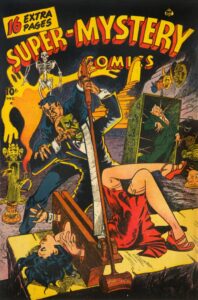

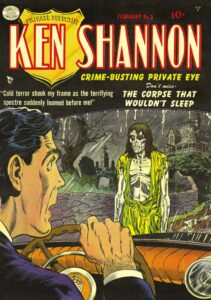

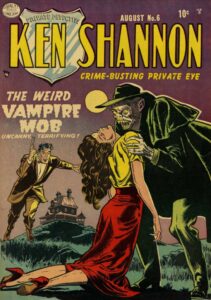

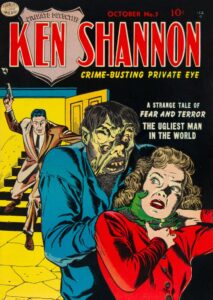

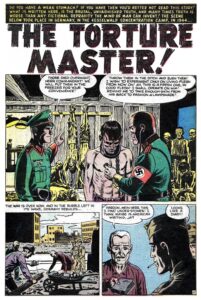

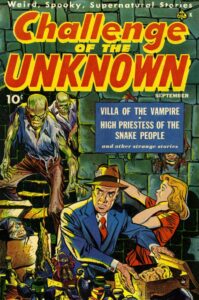

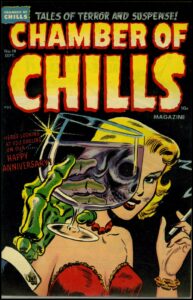

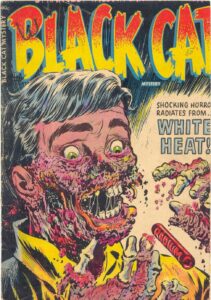

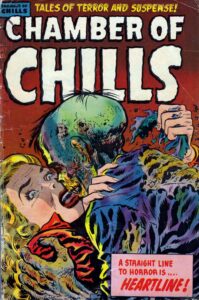

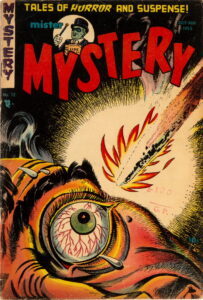

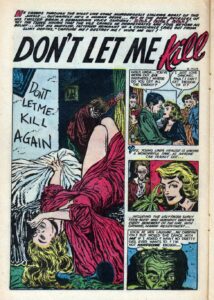

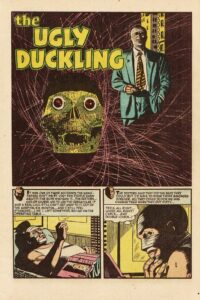

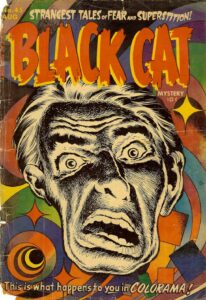

Soon, crime and horror conflated once again as “thrill/spree” serial killers and themes of psychosis and paranoia filled the stands. Falling back on the shocking conventions of the old Weird Menace pulps, savage and graphic depictions of gory murder, dismemberment, torture and other violent extremes filled adult crime comics by the second half of the forties. Drug addiction, prostitution, juvenile delinquency, war atrocity, necrophilia, creatures from beyond the grave, nothing was off the table. There were even Private Eyes who worked a horror beat directly.

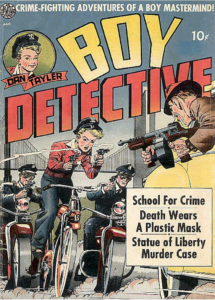

Among the carnage, a few maverick publishers tried advancing the medium with new directions, more literate, mature writing and themes, better artwork and experimental storytelling. But the tabloid, populist approach in comics remained dominant, whether “True Crime” stories were true or not. It sold and it was what the public wanted. So…if it bled, it led.

Certainly, a lot of this fascination with dark and violent content was a nation’s collective wartime PTSD, with no clearly defined, healthy boundaries in sight. Everywhere, civilization was recovering from the devastating effects of global conflict. Chaos still reigned in many countries. Youth was in revolt. Entire populations were trying to reconcile with new realities of mass genocide and atomic destruction, broadcast and recorded in real time for everyone to see and no one to deny. This was “War’s Peace,” the aftermath, the period of noir.

Some coped by seeking truths and facing harsh realities head-on. Others turned away, seeking comfort and escapism in reassuring justifications of the moment, truth be damned. Either rationale provides emotional satisfaction, but only one is grounded by fact. In such circumstances, the factual approach can ultimately generate a free-thinking, compassion-minded individual. The other, ultimately, only generates sheep.

Among those who strove to be the post-war shepherds, some had motivations that were political, others spiritual, still others just business. They were also opportunistic, and sensed their time had come. Crime and horror comics were the perfect targets for their crosshairs.

But before they trained those collective sights…just who exactly were these predators in shepherd’s clothing? Where did they come from, and how did they come together?

Turns out, the FBI, the Republican Party, Big Business, and evangelical religious groups associated with racist White Identity politics, all merged to convince the USA that it was under attack from within.

Stop me if any of this starts to sound familiar.

To Be Continued…