By Dale Berry

MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

With an Edgar Award category for “Best Graphic Novel”, and graphic short fiction appearing in Alfred Hitchcock’s and elsewhere, the crime and mystery community has come to embrace the modern comic book.

Well…why not? And what took so long? Many an author started by reading comic books and comic strips as a kid, before graduating to novels, short stories, TV, and films. (Show of hands…?) And many have begun to cross over between the trench coats and the spandex. Writer’s gonna write, after all, regardless of format or subject, just as long as the imagination is sparked.

One doesn’t have to look far to find the high-quality work of John Wagner (A History of Violence), Andrew Vachss (Hard Looks, Batman: The Ultimate Evil), France’s Jean Van Hamm (Largo Winch), Ed Brubaker (Criminal, Gotham Central), David Lapham (Stray Bullets, Murder Me Dead), Gary Phillips (Vigilante, Angeltown), or Max Allen Collins (Road To Perdition, MWA Grandmaster). And that’s just to name a few. Comics are now widely regarded as yet another tool in the writer’s kit.

But as they say, there’s nothing new under the sun but the history you don’t know. The tradition of crime and mystery authors contributing to comics is almost as long as crime and mystery have been a part of comics itself. And the genre, whether it’s in novels, pulp magazines, radio dramas, films, or comics, has always reflected the fears of its times.

So, in the interest of ratiocination, let’s follow the clues and through-lines of that history. Trace the red string on the Evidence Board, so to speak, to the threads connecting titles and characters, authors and artists, publishers, personalities, and times that brought crime to the comics, comics to the world, and brought us to where we are today. It’s time to get nerd-core! Strap in—there are a lot of unusual suspects.

Those threads begin in the early part of the 20th century, as social, political, and economic upheavals, and an increase in American violence during the years surrounding WWI and the 1919 Volstead Act, culminated in a rise and solidification of organized crime. Things were tough all over, and popular entertainment reflected this new reality accordingly. Fiction began tackling the subjects of gangs and secret criminal organizations, P.I.’s and police procedurals with renewed interest.

By the mid-to-late 1920’s, Black Mask magazine had shifted from traditional mysteries, in the classic vein of Poe, Du Maurier, and Agatha Christie, toward the hardboiled language of Carol John Daly’s Race Williams and Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest. Elsewhere, movies and radio plays, reflecting the headlines, began spinning dramatic, social-realist yarns about the underclasses and the underworld. The Great Depression descended, the gangster era had arrived, and America was worried.

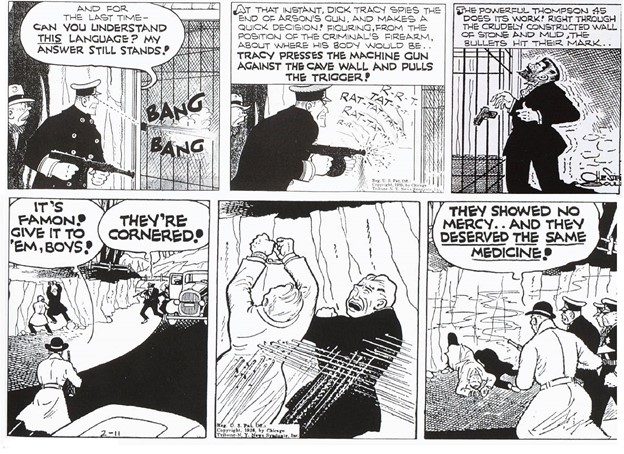

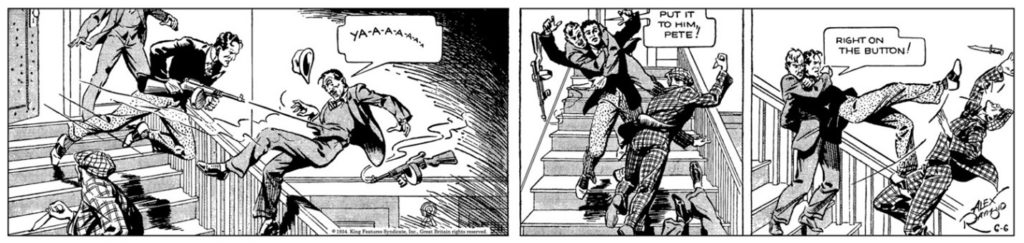

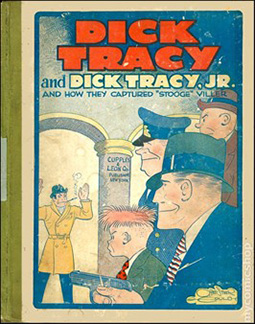

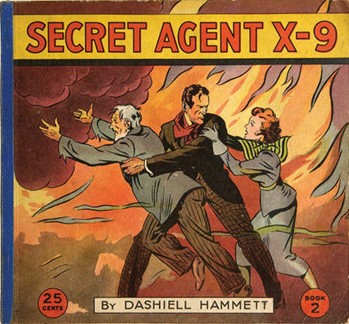

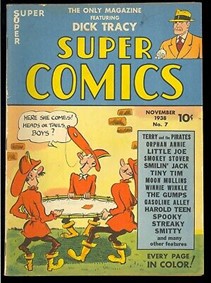

As a response, in 1931, cartoonist Chester Gould created the newspaper comic strip Dick Tracy for the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate, peppering the nation with daily doses of alarming violence, twisted criminals, rough justice, and some real police forensic techniques. It was a major hit. Then in 1934, to compete with Dick Tracy, King Features Syndicate hired Dashiell Hammett himself to create the comic strip Secret Agent X-9, illustrated by the creator of Flash Gordon, Alex Raymond. Hardboiled crime could now be seen, and not just imagined.

Viewed through a modern lens, the violence of these ostensibly ‘family’ entertainments can seem graphic and shocking, but to a nation wearied by hardship and memories of the recent war and its aftermath, it all felt appropriate and cathartic.

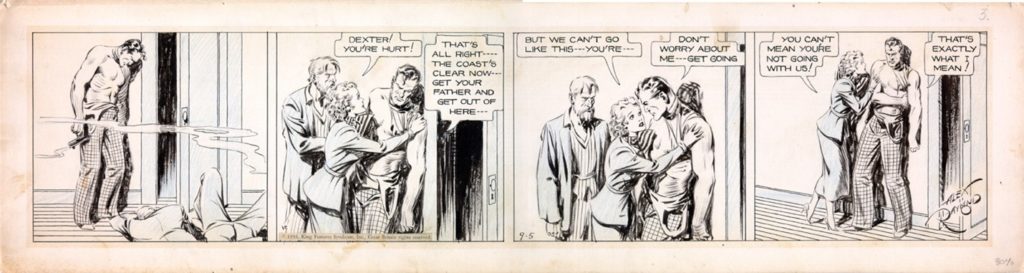

By 1936, Hammett had moved on to greener (well…more alcoholic and controversial) pastures, to be replaced by none other than Leslie Charteris, creator of The Saint. And Alex Raymond would eventually be supplanted by Austin Briggs, legendary American illustrator of Saturday Evening Post and Reader’s Digest fame (and who’d later go on to found the Famous Artist’s School in 1948 with Norman Rockwell and others). The amount of notable talent King Features invested in the series is a reflection of just how topical the subject matter was to the country, and increasingly, in Europe.

Secret Agent X-9 (whose agency was revealed to be the FBI, by the way) would undergo a name change in the 1940’s to Secret Agent Corrigan and continue to solve crimes in the funnies until 1996. Dick Tracy, across time and multi-media, is still with us. Between them, these strips would define the range of crime’s visual style in the comics, from cartoon to realism, and help open the floodgates for a host of hand-drawn investigators of every physical size, shape, color, gender, personality, or even species, imaginable.

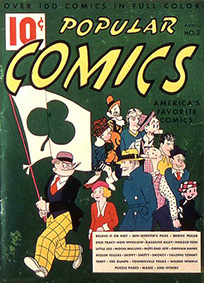

As far back as the 1920’s and earlier, books and pamphlets had been reprinting collections of newspaper comic strips. These were easily mass produced, inexpensive, and profitable publications that proved successful.

By the early 1930’s, the market had greatly expanded, with reprint periodicals coming out monthly. Some, with titles such as Famous Funnies, Popular Comics, Crackajack Funnies and Tip Top, would appear on the stands for decades.

But available strips quickly began to be used up or became too expensive to keep licensed from notable creators and powerful newspaper syndicates. Soon, demand arose for affordable, original material. As the Depression worsened, many would-be writers and cartoonists, facing economic hardship, leaped into the fray. Studios and collective ‘shops’ of writers and artists were formed, ready to supply the demand.

These new comics periodicals would feature all the popular, escapist, trending genres and tastes, copied from movies, radio plays, the funny papers and pulp magazines: romance, sports, adventure, comedy, the Western. Mystery-detective tales escaped right along with the rest…but now in snappier, bite-size stories, with more visual impact, and more punch.

And according to all the available evidence, it’s the mystery-detective genre that gave birth to the comic book as we’ve now come to recognize it.

To Be Continued…

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only. Dick Tracy and Secret Agent X-9 are copyright by The Tribune Content Agency and King Features Syndicate Inc. respectively. All others are public domain.)