MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

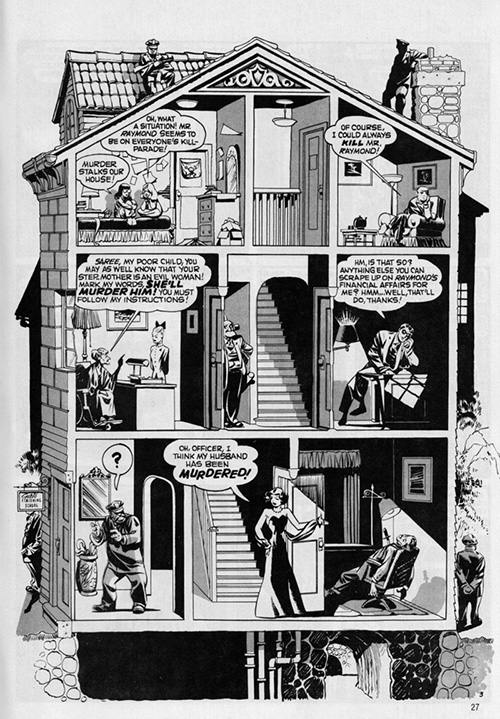

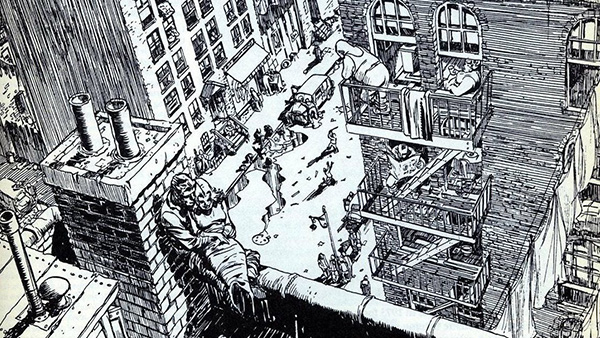

Many stateside writers and artists had worked steadily through the war years, diligently improving their craft. Many who had enlisted or were drafted into WWII had been given additional training in military graphics ;departments or found advanced Art School classes on the G.I. Bill. They now all came to the comics industry with new skills and the need to express them. Plot, dialogue, and characterization began to have an edgier, more adult feel. Artwork began to rely on more sophisticated, commercial art techniques. Traditional comic strip-inspired cartooning gave way to rendering with more realism. Page layout and panel-to-panel continuity, the ways in which a comic book is read and the story is visually told, began to take on more cinematic, sometimes almost expressionistic, dynamism.

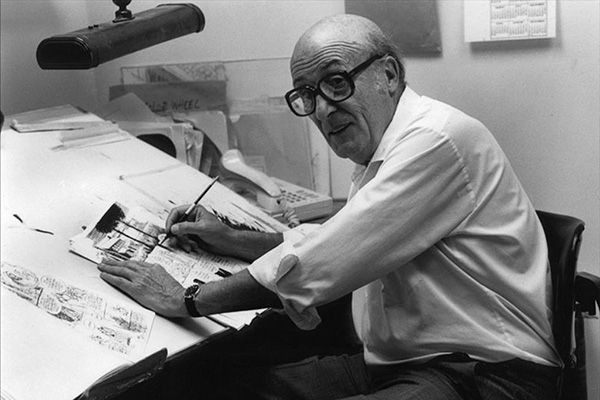

One person who led the way, in more ways than one, and who communicated most the sheer possibilities available within the medium, was a man named Will Eisner. Directly or otherwise, across the history of comics, all the threads on our Evidence Board can eventually connect with him.

He was born in a crime-ridden Brooklyn, New York City, in 1917 to a poor immigrant family. His mother was an orphan and illiterate, his father made a living painting backdrops for vaudeville and the Jewish theater. Growing up with a love of books and art, movies and the pulps, Eisner began creating comics professionally in 1936 at age eighteen, after working as an advertising cartoonist for the New York American and a pulp magazine illustrator to help support his parents and siblings during the Depression.

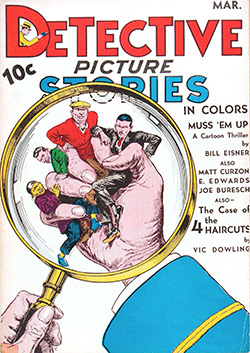

In 1937, as a young man with a keen sense for commercial trends, he contributed to one of the first, original-content crime comics with a strip called “Muss ‘Em Up” in Detective Picture Stories, featuring a Dick Tracy-esque, hardboiled cop named “Hammer” Donovan.

Very soon, he was part of a studio ‘shop’ where he developed, packaged and supplied companies with characters and stories, sometimes entire books, Eisner would go on to create some of the most popular characters in comics, such as Blackhawk and Doll Man for the Quality Comics company and Sheena, Queen of the Jungle for Fiction House.

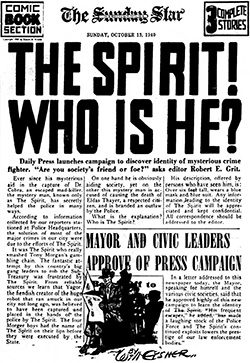

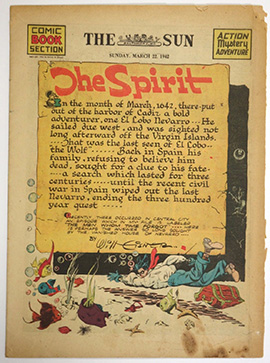

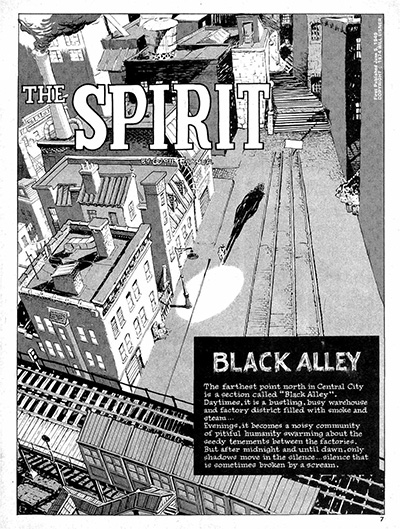

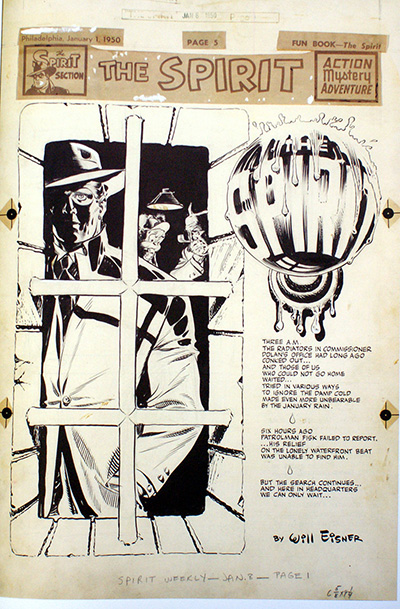

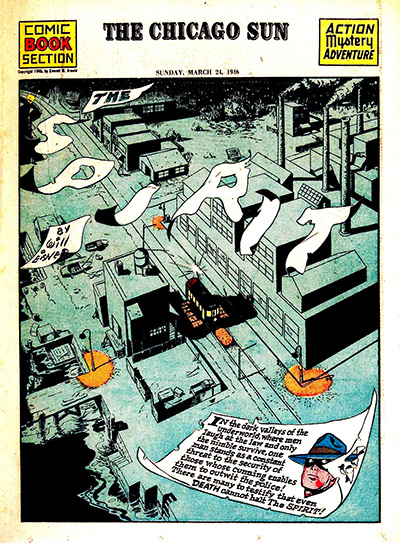

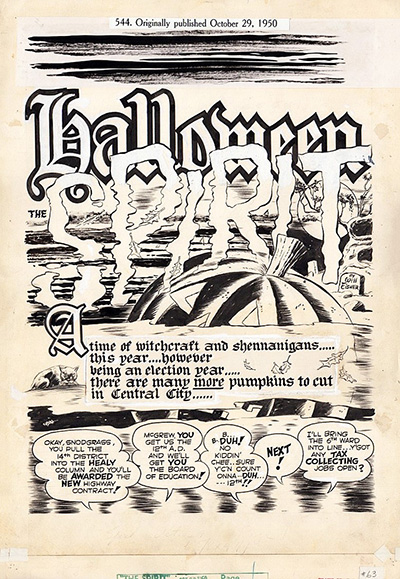

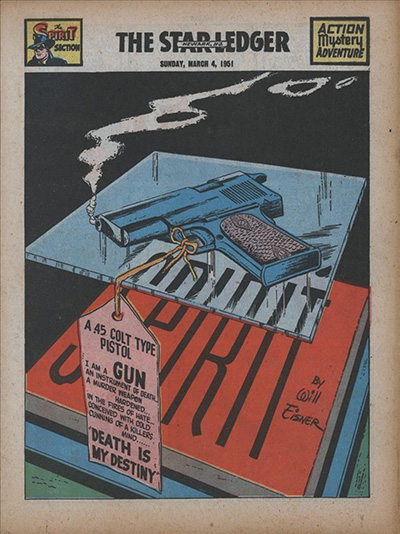

A canny businessman and acknowledged early success, in 1940, Eisner packaged and syndicated his own masked mystery man character, The Spirit, in its own weekly comic book supplement to newspapers across the country, exposing him to a readership circulation of five million. These ‘Spirit Sections’ would run until 1952, and in reprints even longer. Drafted into the Army in 1942, Eisner helped develop cartoon magazines and pamphlets for the military to use as teaching tools for soldiers, creating in the process the very first educational comics. Many of his creations are still to be found in comics and other media today.

All of which would be quite enough for anyone’s career, but upon returning to The Spirit after the war, Eisner’s creativity would explode further, and revolutionize the medium. Imagine Citizen Kane’s visual storytelling, but in the service of a working-class, schlemiel crimefighter. That was the secret of its humor, and its impact. It made comics seem brilliant.

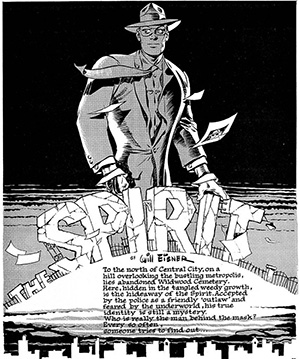

In 1940, The Spirit began as criminologist Denny Colt, who had survived a near-fatal encounter with the evil Dr. Cobra and ‘returned from the dead’ to fight crime. He operated from a secret hideout under his own grave in Wildwood Cemetery, with support from his old friend Police Commissioner Dolan, the commissioner’s daughter Ellen, and his young taxi driving assistant Ebony White.

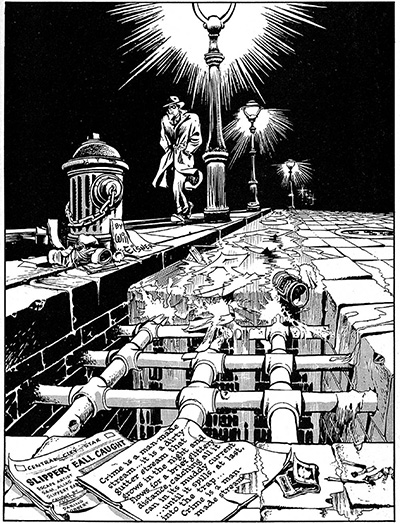

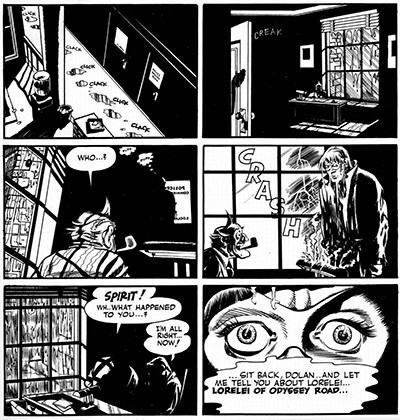

Known only as The Spirit (his “Denny Colt” identity mostly disappeared), wearing just a frumpy business suit, hat, gloves, tie and domino mask, the character took on a multitude of violent criminals and dangerous, sexy femme fatales in adventures that led him down the grim, shadowy streets and alleyways, low-rent tenements and backrooms of the modern big city. An almost classic hardboiled pulp/comic book set-up.

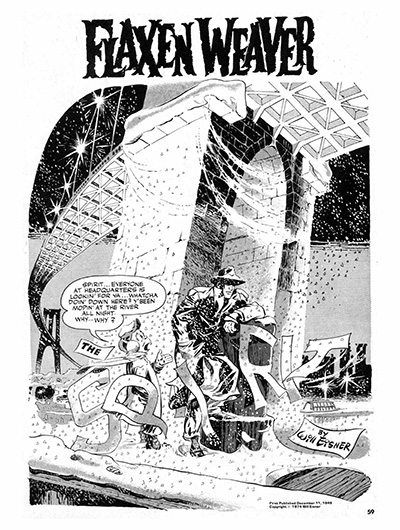

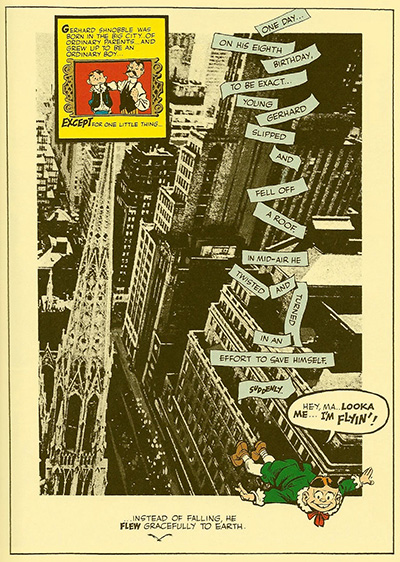

But avoiding most standard comic book hero cliches, or satirizing them outrageously, the returning Eisner’s post-war ‘Spirit Sections’ would instead focus on short stories and serials that delivered on both laughs and profoundly human drama. Within its “vigilante vs. crooks” framework, the title went anywhere—from crime and mystery to social satire, horror to screwball comedy, sci-fi to fairy tales, small-town Middle America to the Sahara Desert. Sometimes, all at once.

It was a series whose default setting was film noir before the term existed, with compelling characters adult readers could relate to, Damon Runyan-ish storytelling and art that delivered with an often dark, cinematic atmosphere of sophistication mixed with wacky experimentation. It became a series in which nothing was off limits; capturing the mood of the era like a glove and inspiring many with its cleverness and originality. Will Eisner’s own staff would come to include and develop such future talents as fantasy author Manley Wade Wellman, novelist William Woolfolk, commercial illustrator Lou Fine (Remember those golden Peachy folders everyone had in school, the ones with all those sports figures on them? Well, Lou Fine drew it.) and Jules Feiffer, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist, playwright, screenwriter and author.

In the ensuing years, Eisner would further develop educational and instructional tools for the Pentagon and related government agencies, RCA Records, New York Telephone, and even the Baltimore Colts NFL team, as well as many other industries. His love of comics was never far, however. In 1978, he helped pioneer the modern graphic novel, writing and illustrating the best-selling, award-winning A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories, published by Baronet Books. Several more works would follow, helping to popularize the form with readers and mainstream publisher’s alike, and paving the way for such modern classics as the Pulitzer prize winning Maus by Art Spiegelman.

In 1995, during a point when comic book publishers were facing an economic crisis and near industry-wide collapse, I personally watched reps from the major companies, each one a ruthlessly competitive business rival amidst a congress of industry professionals, seek out Will Eisner to ask his advice. Now, years later, you can see the results spread everywhere across the cultural and commercial landscape.

Eisner would go on to lecture and teach at the School of Visual Arts in New York, and based on his lectures, create Comics and Sequential Art and Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative, both of which have become textbooks. They are considered indispensable to students in the field of cartooning. His final graphic novel, The Plot: The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a refutation, expose and history of the antisemitic hoax, was completed and published in 2005, just prior to his death.

So, in the end, there’s no real mystery why, in 1988, the Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards were established in his honor. They’re the industry’s proud equivalent to the Oscars, and they’re named for the one person most responsible for the comic book’s creative influence on everyone’s life. Whether they know it or not.

To Be Continued…

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only. The Spirit and its related characters are copyright Will Eisner. Original black & white art from Will Eisner’s The Spirit: Artist’s Edition. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright all respective creators, unless otherwise noted.)