MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. All dime novel images are courtesy the Johannsen and LeBlanc Collection from the Rare Book and Special Collections at Northern Illinois University, and its site Nickels and Dimes. The Spirit and its related characters are copyright Will Eisner. Nick Carter, Doc Savage and The Shadow are copyright Conde Nast and associates. Young Allies, Fantastic Four and Black Panther and all related characters are copyright Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Worldwide Inc., a division of The Walt Disney Company. Lobo is copyright Dell Publishing. Friday Foster is copyright the Chicago News Syndicate. All others are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

[WARNING: Contains racist and explicit imagery.]

American exceptionalism has always been a blessing and a curse. Our first colonial founders were staunch believers in democratic self-rule, but were financed by and beholden to some of the earliest overseas global corporations ever formed. Escaping violent religious oppression, they believed in religious freedom and preached of a model society, but only for those most racially like themselves. Soon would follow mass slaughter for the people found to be living here first. And on it went. Seemingly every progress America discovered for itself, it also attempted to destroy. From equality to jazz, atomic power to comic books, nothing our nation has developed has come without internal conflict and a human cost.

In this nation of immigrants, where even those born here trace their roots to those who didn’t, racism and its twin correlatives, ethnic and cultural imperialism, were ever the Achilles’ Heel…even for a land where it was held self-evident that all were created equal, and endowed by the creator with inalienable rights. Humans, regardless of shape or tint, are recognized by science universally as the same, and race is defined by scholars as a social construct, a designation recognized within a society that comes with a set of assumptions and rules. Time and again, the racially outcast and marginalized populace were often forced into a life of crime by the ones who seized leadership, and who treated others as outsiders and non-human livestock.

And here is where the red thread of our Evidence Board connecting comic books with the crime and mystery genre crosses into some very conflicted and complicated territory. And realms of actual historical crime.

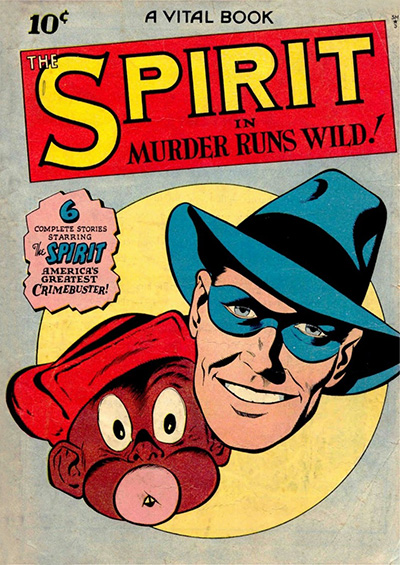

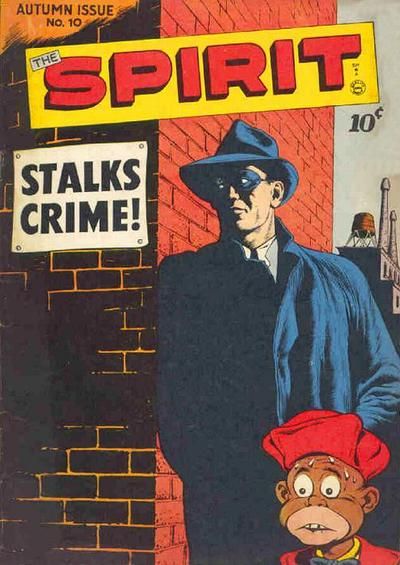

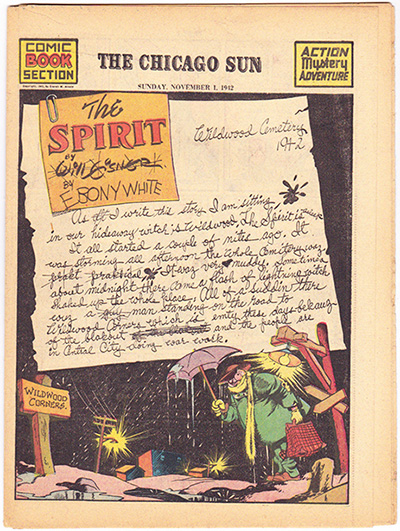

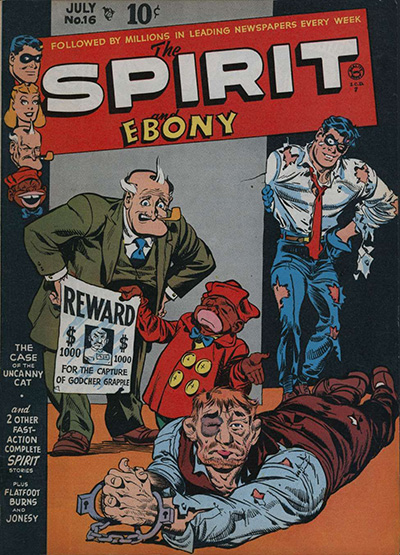

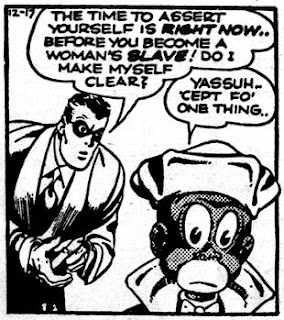

In 2003, discussing the character Ebony White from his series The Spirit, author and artist Will Eisner, considered one of the major creative forces in the history of comics, wrote of unintentionally “feeding a racial prejudice with this stereotype image…I never recognized that my rendering of Ebony, when viewed historically, was in conflict with the rage I felt when I saw anti-Semitism in art and literature.”

Later, he’d reason, “This was my first real attempt at out and out comedy. It was also a chance to develop Ebony as a real human. Remember, I was still living in a world of Amos and Andy. But I was struggling with an idea that kept running around my conscience like a piece of quicksilver that cannot quite be picked up by hand. No one really—in big time comics—devoted much time to a black man as a human alone. In retrospect, I’m embarrassed by what I frankly regard as a cop-out. That “Yassuh Boss” bit makes me cringe to look at it again…I was still pretty glad for the chance at the Big Time and I was not strong enough to challenge the establishment.”

And interviewed in 2011, Eisner revealed: “At one point, I think it was somewhere around 1949, I got, strangely enough, two letters in the same day, one of those rare coincidences. One letter came from the Education Division of the CIO in Philadelphia. It happened to be from a fellow who went to school with me or something, and he wrote a long, bitter letter about how he was shocked, and dismayed, and disappointed that a fine liberal like me had gone down the road of portraying Negroes in this fashion.

“On the same day, I had this long and wonderful letter from the editor of the Afro-American newspaper in Baltimore congratulating me on the courage that I was displaying in showing a character like that. Now the strange thing about it is that neither of these fellows was quite right. I was neither a defrocked liberal, nor was I setting out to do any more than what I thought was right. I treated Ebony in the scheme of things as it was then. To me, Ebony was a very human character, and he was very believable…With all the idealism I had then, I felt he deserved to be treated as a human being and have emotions. Remember, that was a breakaway in itself.”

Well, yes and no…as we shall see. Ebony White was treated with a great deal of affection and development, respected as an equal cast member of The Spirit, given center stage, a chance to drive the action, and personal agency more often than most other characters of color in mainstream comic books. In his post-war stories especially, Eisner was a good enough writer to avoid most cringe-inducing moments and make us want to invest in the character’s drama. Which is why, despite being drawn and speaking in classic minstrel show fashion, Ebony White is often given a pass. He was no more or less cartoonish than The Spirit himself, or other characters in the series, and compared to the fanged, cackling Nazi grotesques and bucktoothed, lemon-yellow ‘Oriental’ fiends of the era, anyone could identify with him.

Sadly, Eisner’s approach reflected the country’s tendency toward broad generalizations, derived from ignorance of its multicultural immigrant experience, and an individualistic drive to show that every citizen was responsible for making it on their own. Many in the 19th and early 20th century, desperate to rise above widespread poverty, began in isolated communities where education was often catch-as-catch-can. So exaggerated racial and ethnic caricatures of Irish and Italian, Jewish and Scandinavian, Asian, Hispanic, Native American, and African-American peoples, drawn broadly and speaking in dialect, were the norm. People were reduced to symbols, a fast, simplified way to understand a diverse world many had never encountered before, or might ever encounter.

Doing so would also prove to be wrong and reductive. It actually reinforced a status quo that already kept people apart, and helped to promote the very isolation and objectification of others that the country was supposed to stand against. It fed into hate and led to the Law of the Jungle. Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Because in the end, with everyone struggling to get ahead of the next fellow, someone will always be trying to reach the top at that next fellow’s expense. And everything was not equal.

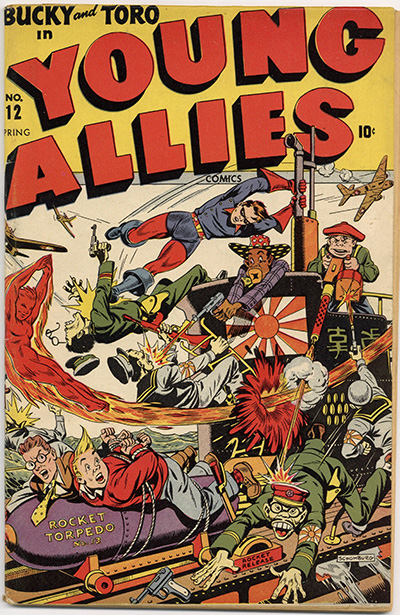

Prejudice and racist tropes were nothing new in American popular fiction, having been around since before the country’s founding. On arrival, they were de rigueur in plays, music, art, and literature, high and low. They were thoroughly mainstreamed by the 1930s (although British, Agatha Christie’s 1938 novel 10 Little Ni**ers is an obvious example) and could be found in trace elements even well into the 1980s. (Yellow skin coloring on Asian characters, anyone? Ah, so! Indigenous people speaking in monosyllables? Ugh, kimo sabe! Umgowa!)

Perhaps the apogee would be in WWII comics such as the one above, where cartoon minstrels in zoot suits shoot cartoon buck-toothed Japanese in glasses. Stereotypes battling stereotypes. And no question about children toting machine guns and engaged in mass slaughter, either. This was war!

Looking back now at how blatant the racism could be, what’s most surprising is, even after being proven false and outmoded time and again, just how tenaciously it fought to remain and how long that fight has lasted.

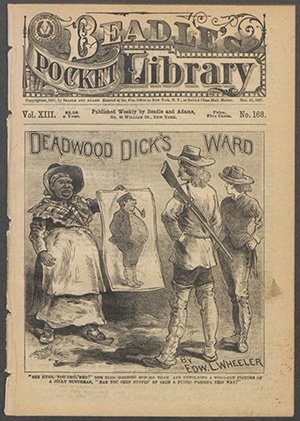

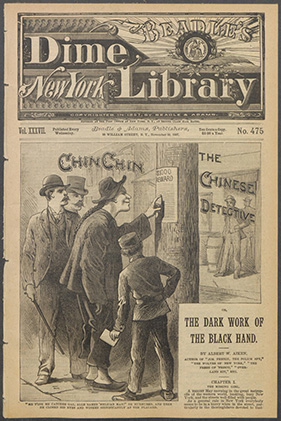

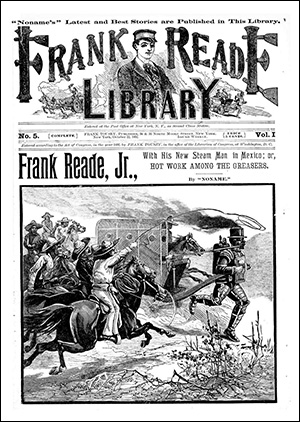

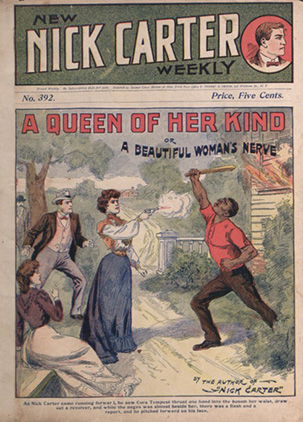

Detective and mystery fiction appeared in American story papers, nickel weeklies, and finally dime novels as far back as the 1840s, joining westerns, romance, historical adventure, sci-fi, sports, and humor stories, to become the dominant genre by the 1880s. It remained so until the format’s demise and then made the jump into the pulps. And if derogatory, racist stereotypes were normalized across most genres in popular literature, including crime fiction and later by extension in crime comics… who read them, who published them, who didn’t, and how did things start to change?

Let’s start with that last one first.

In the war’s aftermath and the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau, northern teachers—known as the “Soldiers of Light and Love”—traveled South to establish schools and ease the adjustment of ex-slaves to freedom. These schools, however, were located in the cities and not in the countryside, where most southern blacks lived, and few adults benefitted. By 1880, when government studies began, southern white illiteracy was 21.5%, and black illiteracy was 76.2% (54.7% greater than for southern whites). But by 1890, black illiteracy stood at 61%, down 15 percentage points, and by 1900, more than half claimed to be literate. Though the gap was still considerable (36%), the postbellum decline in illiteracy was greater in blacks than in whites. The black illiteracy rate continued to fall in the first half of the 20th century, driven by black women and younger student cohorts, down to slightly more than 25% by 1920. By 1950, between 88 and 91 percent of all southern blacks were literate.

White illiteracy also fell between 1900 and 1950, but at a slower pace than American blacks. Consequently, the racial gap in literacy also fell steadily. In 1910, that gap stood at 25%. But by 1950, that gap had dropped another 7-9 percentage points, which made black and white illiteracy rates almost equal. This was despite forced shorter hours, shorter school years, and lower budgets in the South for black schools.

Coincidentally, the years 1900 onward—a time period that found southern blacks becoming more educated, more financially empowered, and voting more—also parallel the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, the Daughters of the Confederacy, the veneration of the Lost Cause, renewed acceptance of eugenics as ‘proven science’, and the emergence of the Jim Crow laws. Also, lynch mobs.

Yet following WWI, as a direct response to acts of repression and violence, the flowering of the “New Negro” literary movement (who in fact often wrote in dialect and defended its use as a way of documenting an authentic folklore) and the Harlem Renaissance (1919-1939, and who rejected dialect overall in favor of newer, progressive ‘jive’) each made profound impacts on drama, fiction, poetry, music, cinema, and other forms of artistic expression, first in Europe and then in the United States. Which no doubt contributed to southern white unease and to its doubling-down on its traditional values.

Comic books, meanwhile, were populist, a cheap consumer product for the masses. Seldom designed to be of high literary caliber, you didn’t have to read much to look at the pictures and follow the story. They were predominantly created, published, and distributed by white men with relatively little exposure or knowledge of the black experience, working in the traditional styles and forms of pulps, comic strips, and other media. Civil rights weren’t high on their agendas. They thought mainly about profit and volume sales.

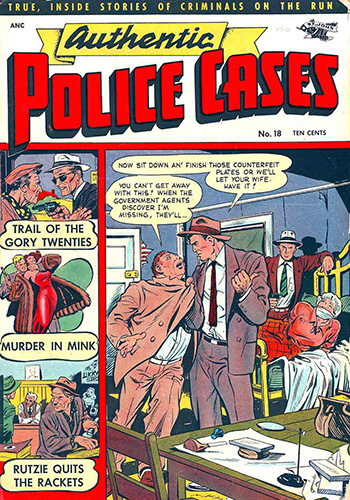

The average, random comic book in the 1930’s-40’s had a print run of around 350k copies per issue, and at 10 cents each had to sell at least 50–60% of its printing just to break even. Wholesalers paid 6 cents a book, sometimes 5¾, and charged retailers 7½ cents. Publishers grossed 5¼ cents for each sale, retailers made 2½ cents, and, after kickbacks, wholesalers 2¼ cents. At those margins, few were willing to jeopardize profits by trying anything too radical or progressive. If the quickest way to crank out a story was to use traditional racial caricatures, speaking in broad dialect, and played for laughs—and if large, predominantly white-controlled, low-literacy markets like the Jim Crow American South represented consistent financial returns on undemanding material—well, there was no reason to change anything. The masses spoke through a cash register.

While the South may be an obvious example, in general, the problems of representation were as widespread as the response was inconsistent. In cosmopolitan New York City, the heart of American publishing, companies would hire artists of color but put them to work illustrating white characters. For years, what passed for progressive editorial policy ranged from “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” to “Separate, But Equal.”

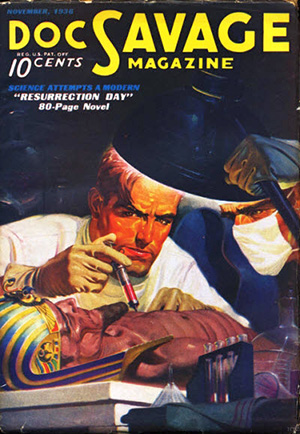

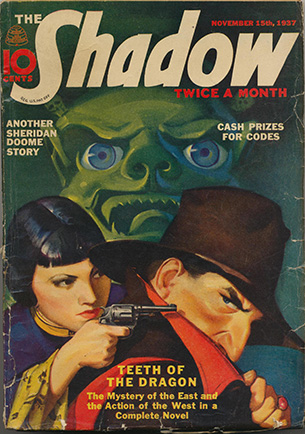

For instance, editors at Street and Smith, publishers of The Shadow and Doc Savage magazines, would change the racial identity of villains in their pulps to avoid “ethnic divisiveness.” One example is in the November 1936 Doc Savage story “Resurrection Day,” where a Japanese general was switched out as the antagonist for generic crooks. A year later, however, The Shadow novel “Teeth of the Dragon” featured contemporary Chinese-Americans versus ‘Yellow Peril’ stereotyped villains (and white characters in “yellowface”) but treated the terms “Chinaman”, “Mongol,” and “Oriental” interchangeably. Still later, elsewhere, Hillman Publications, who published slick magazines, comics, and soft cover novels, would distribute a line of titles for commuters at train station newsstands aimed at black readership. These included books on health concerns, politics, romance novels, and even science fiction.

Will Eisner, needing to escape poverty and get ahead, took the approved way and thought in terms of the cash register as much as self-expression. He did what was expected of him and changed things as opportunity allowed and he evolved. Ultimately, he came to see the medium as not simply a commercial venture.

But other artists were working for change also and some of them were not white. That first early wave of comics creators in the thirties and forties included black artists, as well as other artists of color. Some resorted to racial caricature as publishers expected. But some had other agendas, even as The Spirit’s Ebony White was being viewed by five million readers a week.

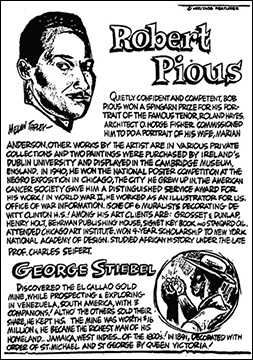

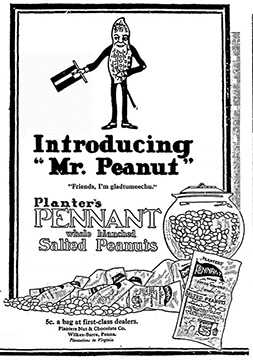

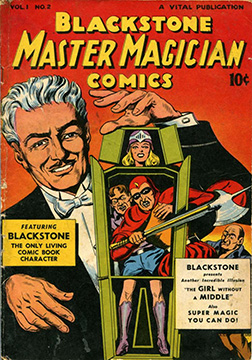

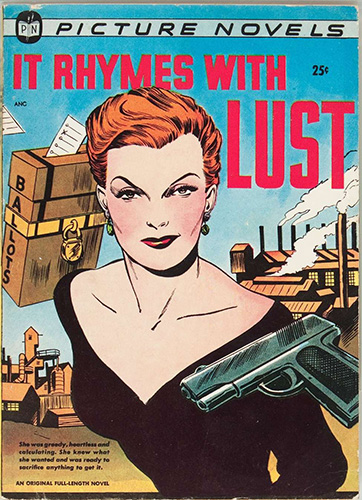

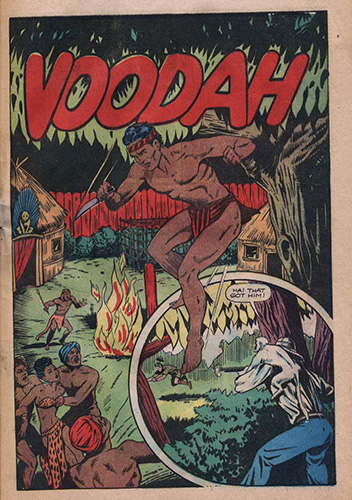

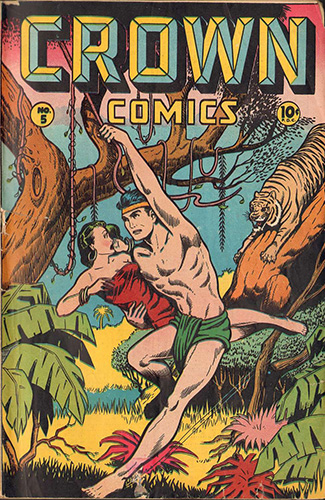

These black creators who drew mainly white characters included Robert S. Pious, who did pulp illustrations, jungle adventures, and wartime aviation comics, later becoming a nationally recognized fine artist whose painting of Harriet Tubman now hangs in the Washington D.C. Smithsonian Portrait Gallery; in 1917 Elmer (E.C.) Stoner, the creator of Planters’ “Mr. Peanut” mascot, drew the popular superhero Blue Beetle in the 1940s and partnered with The Shadow creator Walter Gibson on Blackstone the Magician for Street & Smith’s comic book line; and, finally, the fabulous Matt Baker, a slick and stylish illustrator in virtually every comic book genre, from crime to Westerns to romance, who was even an early pioneer of the ‘graphic novel’ format with the noirish, novel-length one-shot crime comic It Rhymes With Lust (St. John Publications, 1950). In 1945 in Crown Comics, Baker would also draw the first jungle adventure series in which the hero was actually a black tribesman (Voodah). Worried about reader response, or maybe just out of habit, the publishers colored Voodah white after six issues and on all the covers.

But all the while, black-owned newspapers had been in existence since the 1820s, first as Abolitionist publications, then in the post-Civil War era to serve the community throughout the nation’s black population centers.

To Be Continued…