MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: Images and samples are for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. EC images copyright the Gaines Family. Suspense, Menace and related materials are copyright Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Worldwide Inc., a division of The Walt Disney Company. Any and all other artworks in this article are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators and license holders, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

[WARNING: Violent imagery]

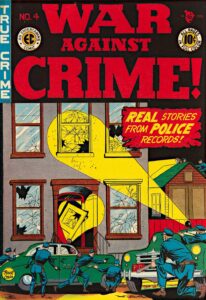

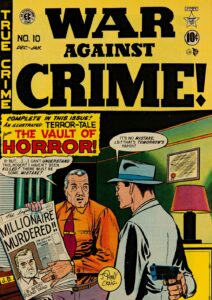

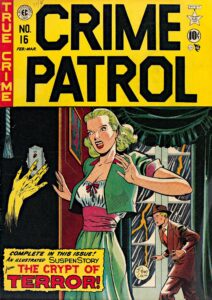

From 1949 through 1952, in the teeth of anti-comics outrage, Bill Gaines’ Entertainment Comics began its ‘New Trend’ line of high quality, thought-provoking and confrontational books.

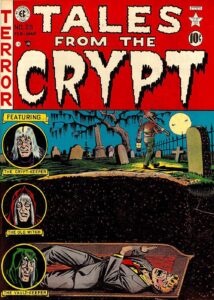

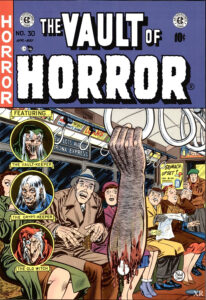

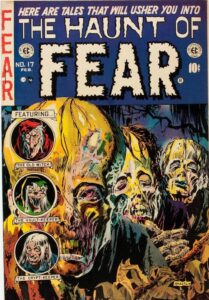

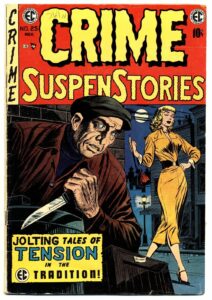

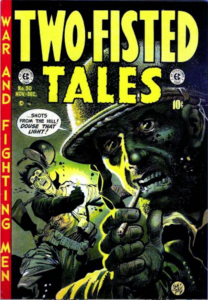

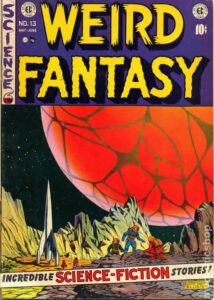

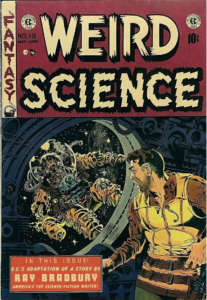

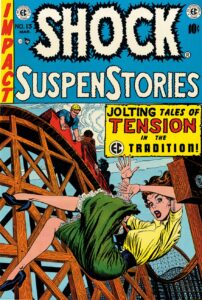

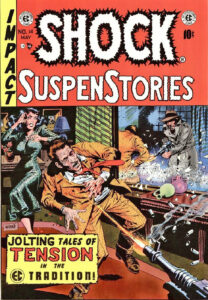

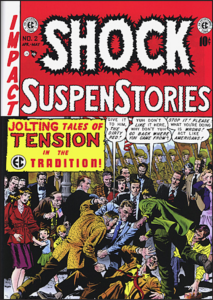

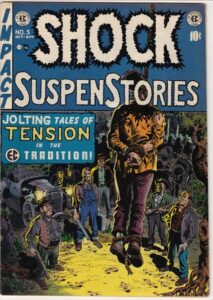

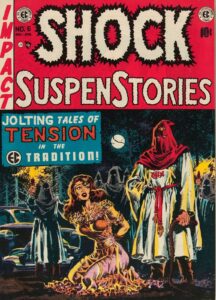

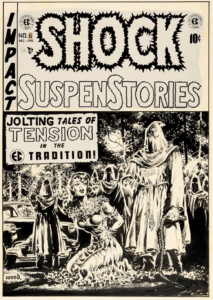

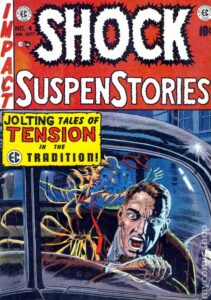

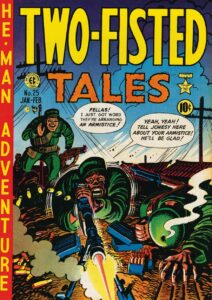

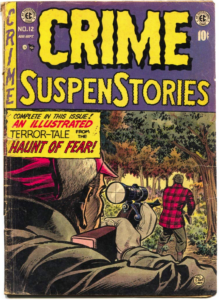

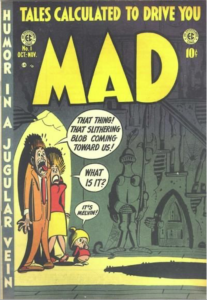

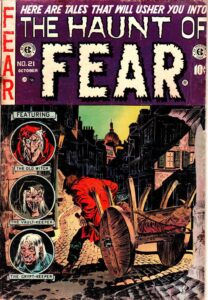

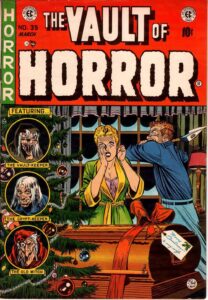

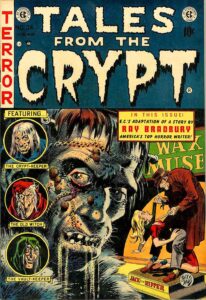

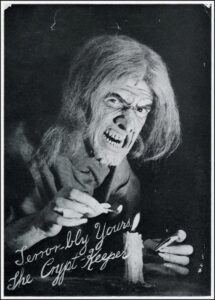

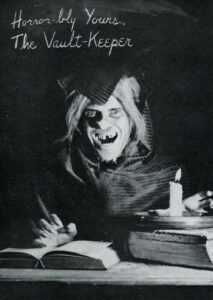

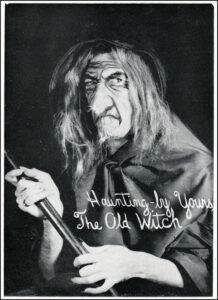

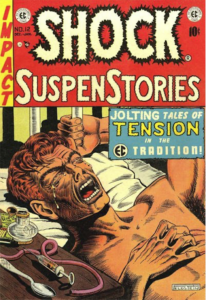

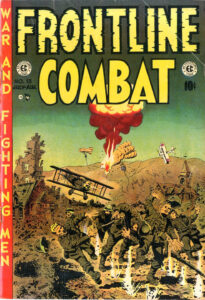

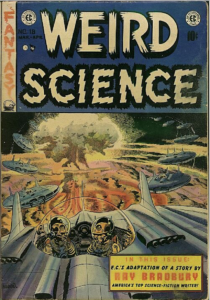

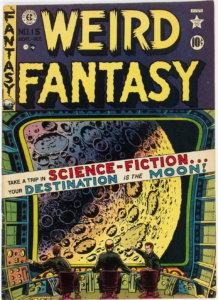

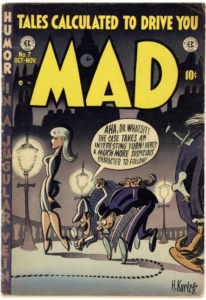

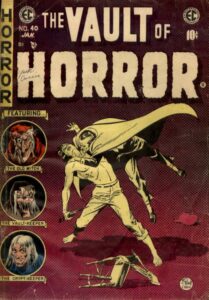

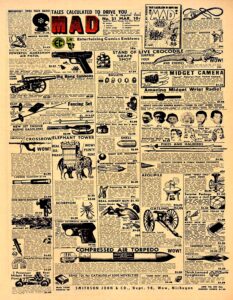

Evolving from its crime titles, EC introduced the gruesome, best-selling horror comics The Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear and Tales from the Crypt. Then the unflinchingly political, socially conscious noir of Crime SuspenStories and Shock SuspenStories; the grim anti-war action of Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat; the progressive, imaginative Weird Science and Weird Fantasy; and the outrageous satire Mad.

His editors Al Feldstein and Harvey Kurtzman drew covers and stories, also hiring accomplished freelance artists like Johnny Craig, Reed Crandall, Jack Davis, Will Elder, Frank Frazetta, Graham Ingels, Bernard Krigstein, Joe Orlando, John Severin, Marie Severin, Al Williamson and Wally Wood. (Google any of them.) With Gaines, stories were written by Kurtzman, Feldstein, Craig and others, including crime/horror novelist Jack Oleck and pulp author Otto Binder.

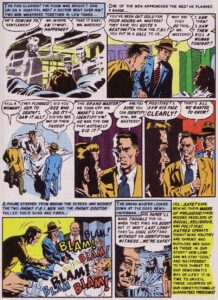

And for six years, some of the best in the business would create some of the best comic books up to that time. EC stories featured mature, dramatic, reality-based morality tales of racism, antisemitism, police corruption, drug addiction, domestic abuse, nuclear disarmament, environmentalism and civil rights alongside all their zombies and vampires, confronting the American Dream and contemporary ideals of post-war suburban domesticity with shock endings and ironic twists.

Tapping into the era’s social undercurrents with cynical humor and youthful revolt, retribution from beyond the grave never seemed so fun…or crime noir so realistic and transgressive. Once mere throwaways, reading comic books now began to feel sophisticated. Quickly, EC developed a large fan following as, boldly pushing the boundaries of what the medium could show and say, their product approached something akin to Modern Art.

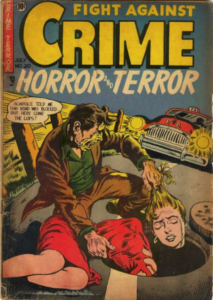

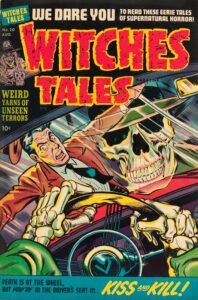

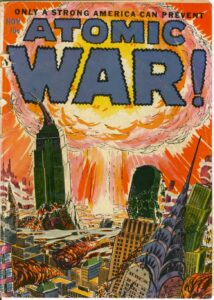

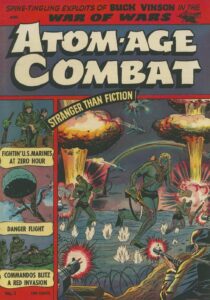

Of course, it was too good to last. Wildly influential, others copied the EC formula, launching their own horror/suspense comics featuring sick humor, grotesque content and varying degrees of creative quality. Which just triggered critics all the more, generating further widespread outrage. Protests and book banning increased, and started inching toward government-sanctioned censorship.

By 1950, Ohio’s Cincinnati Parents’ Committee and Parents’ Magazine began rating comics for safety. Nationally, Today’s Health asked “Are Comic Books a Menace?”. Soon the US Senate formed a bi-partisan Special Committee to Investigate Crime in Interstate Commerce, helmed by conservative Tennessee Democrat Estes Kefauver. On its list: organized crime syndicates, interstate gambling, racketeering and juvenile delinquency—including the related effects of crime comics on the population.

In 1951, New York’s Joint Legislation Committee to Study the Publication of Comics issued its interim report. It’s findings: crime comics were a “contributing factor leading to juvenile delinquency”, and publishers of those comics were fighting efforts to limit publication of crime comics. Evidence gathered by the Joint Committee made “some action by the State imperative to protect its children.” And ominously, it warned “regulation can be self-imposed by [the comic book industry]. It can be in the form of governmental regulation. The Committee ardently hopes for the former.” It also noted patchwork regulations across the forty-eight states could be fatal to publishers.

By 1952, a “major project” by the Austin, Texas PTA sought to “[get] to the heart of the matter in their study of comic books.” And Florida’s West Palm Beach City Commission considered legislation banning the sale of “crime, horror, and sex ‘comic books’.” They were dissuaded when a civic organization worked with local distributors to only prevent sales of “very objectionable” publications.

In April 1953, Dr. Frederic Wertham, failing to stop crime comics but now a nationally recognized psychiatric expert supported by conservatives, was busy preparing a book expanding on his analysis of the connections between comic books and juvenile delinquency. Certain to be a major work given his newfound media acclaim, he was contacted to provide congressional testimony. Preparations taking months, Congress awaited his book’s release.

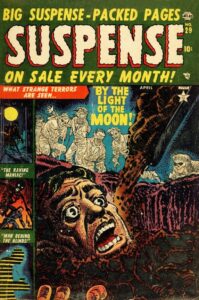

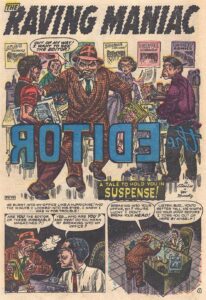

Meantime, the Marvel group’s Suspense #29, a title licensed from the CBS radio show, featured a story critical of comic book hysteria called “Raving Maniac,” written with an EC flair by Stan Lee.

On June 9, Germany’s Gesetz über die Verbreitung jugendgefährdender Schriften law was passed, deriving from the “provisions for the protection of young persons” clause in Article 5 of the German constitution, regulating freedom of expression. That July, Connecticut banned sales of certain comics to anyone under 18.

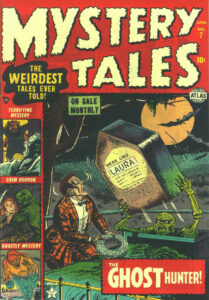

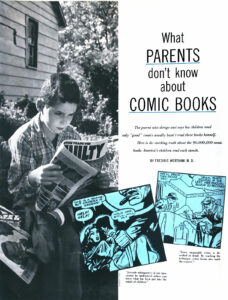

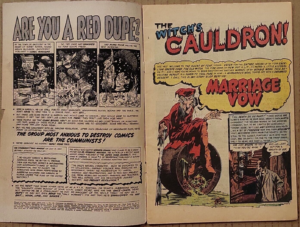

In September, in Marvel’s Menace #7, Stan Lee’s “Witch in the Woods” again satirized the anti-comic book crusade. In November, Ladies Home Journal published Wertham’s “What Parents Don’t Know About Comic Books,” a selection from his forthcoming book.

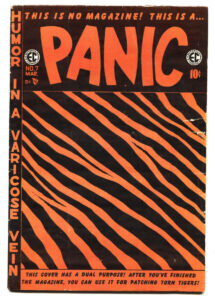

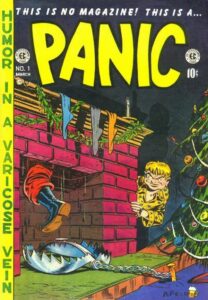

That December, EC launched Panic, a companion series to Mad, featuring a sick-humor retelling of “The Night Before Christmas.” The comic was banned in Massachusetts. Undaunted, EC fought back in court, and the case made headlines, including the NY Times and the Hartford Courant. By February, the Courant launched a series of anti-comics articles later used as congressional evidence (“Depravity for Children—10 Cents a Copy,” “Public Taste, Profit Used to Justify ‘Horror’ Comics,” “Contents of Comic Books Appalling to Civic Leaders” and “State and City Officials Warn Comics Publishers to Clean Up,” 1954).

The NY Joint Legislation Committee issued its final report March 1st, warning: “I think I speak for the entire subcommittee when I say that any action on the part of the publishers of crime and horror comic books, or upon the part of distributors, wholesalers, or dealers with reference to these materials which will tend to eliminate from production and sale, shall receive the acclaim of my colleagues and myself. A competent job of self-policing within the industry will achieve much.”

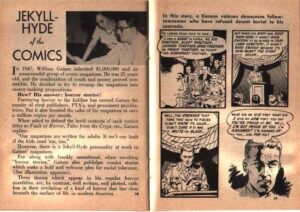

That same month, West Germany created the Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien (“Federal Department for Media Harmful to Young Persons”), a government agency intended to weed out publications, including comics, considered unhealthy for German youth. Stateside, Tops in Human Highlights #1, a news and gossip digest, published “The Jekyll-Hyde of Comics”, an article about William Gaines (featuring Wally Wood illustrations), citing EC’s books as “well written, well-plotted, ruthless in their revelation of the kind of horror that lies just below the surface of life in modern America.” Battle lines were being drawn.

Then the bomb dropped.

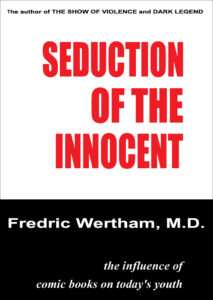

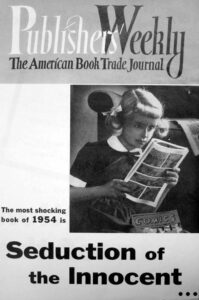

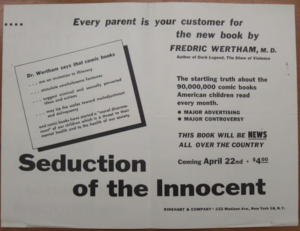

Fredric Wertham’s book, salaciously titled Seduction of the Innocent, was published April 19, 1954. It asserted comic books were a corrupting influence on youth and a leading cause of juvenile delinquency. It cited case studies of comic book violence triggering anti-social behavior and mental disorders in children and young adults. It vilified the crime, horror, jungle and superhero genres, even questioning romance comics and those based on classical literature. It interpreted Superman as un-American and fascistic, Wonder Woman as lesbian and Batman and Robin as gay (at a time when homosexuality was still listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders).

Crime comics in particular promoted violence in children, Crime Does Not Pay and EC books specifically, and even comic artwork itself contained subliminal symbols that unconsciously evocated sexual and violent behavior in readers. Included out-of-context: examples of the most gory and extreme panels, which spread widely through the media. (One graphic EC sequence showing America’s national pastime of baseball, being played with body parts, became especially notorious.)

Shocking, sensational stuff, and as presented by a medical “expert”, influential. Positive reviews in the NY Times and the Saturday Review (by Winifred Overholser M.D., superintendent of Washington DC’s St. Elizabeth’s Hospital and editor-in-chief of The Quarterly Review of Psychiatry and Neurology, no less) seemed to make it all official.

ARCs of Seduction of the Innocent reached the Kefauver Crime Committee. Kefauver had a reputation as a mob buster, and it was an understood fact that the mob had strong connections with the distribution of comics and magazines. Thinking Wertham a useful tool against organized crime within the industry, the doctor’s testimony was fast-tracked. Senate Subcommittee Hearings on Juvenile Delinquency, focusing on comics, were scheduled for April 21-22 (three days after the release of Wertham’s book) and finalizing June 4th.

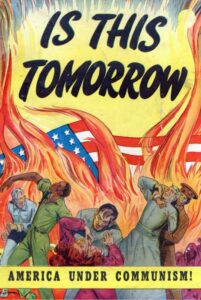

Simultaneously (April-June, 1954), in a multi-pronged conservative attack, came the notorious Army-McCarthy Hearings. Since the 1950-53 Korean War, Sen. Joe McCarthy, assisted by council Roy Cohn (yes, the future mentor of Donald Trump), with information provided by the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover, had equated socialism, communism, disloyalty and “sex crimes” in the public mind, while stoking fear of imminent nuclear attack and takeover by Russia. To drive messaging, they’d exploited all mass media, including the new technology of TV (and, yes, even comic books).

Kefauver’s parallel committee now took on even greater importance. This was a culture war, and within the Right’s nexus of politics, media, ‘patriotism’ and public opinion, a lot was suddenly riding on the comic book’s link to juvenile delinquency.

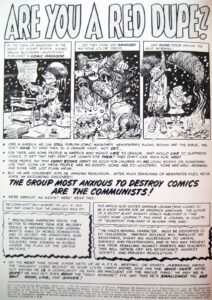

Gutsy EC published a rebuttal/satire of both the “Red Scare” and Wertham (“Are You a Red Dupe?”, Tales from the Crypt #41-46), with an editorial urging action against comic book censorship.

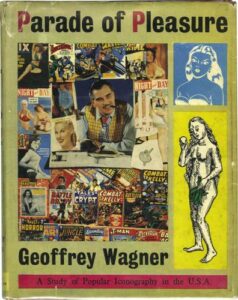

Responding, conservative media increased pressure. That May, during the hearings, Reader’s Digest would print “Comic Books—Blueprints for Delinquency!,” condensed from Wertham’s book, then “For Kiddies to Read” that June. From Britain came Parade of Pleasure: A Study of Popular Iconography in the USA by Geoffrey Wagner, an analysis of “dangerous” movies, comic books, pin-up magazines, television, radio, jazz and murder mystery stories in American culture.

Then the big day arrived. The comics industry was summoned to The Hill.

Wertham testified before the Senate, quoting examples from his studies and his book, claiming the industry was more dangerous for children than Adolf Hitler. (Apparently, comic books spontaneously triggered their own burnings.)

The next witness was Bill Gaines. Questioning focused on violent scenes of the type Wertham disparaged, EC specialized in, and its large readership, sales and fanbase were built on. Gaines argued against Wertham’s assertions, stating he felt proud of the high-quality books he made, the entertainment he provided, the business success he’d achieved and the audience he had created. Opponents took a moral stance against crime and horror comic’s impact on the young, framing EC and Gaines as prime perpetrators. Gaines fundamentally rejected this, but his reasoned testimony was regarded as testy, and an affront. The Senate also didn’t appreciate EC’s “Red Dupe” barb.

Featuring psychiatric professionals on both sides of the argument, and representatives from DC, Marvel, Dell and others, plus sharp scrutiny given briefly to the monopoly of Donenfeld’s distribution outfit Independent News, the hearings were broadcast live on television and made headlines nationally on the NY Times‘ front page.

But just days later, while investigating “communist infiltration” in the US Army, Congress, the State Department and public schools (destroying careers and driving at least one person to suicide), Sen. Joe McCarthy was publicly discredited on live TV during his own hearings when giving false and exaggerated evidence.

Also, an article about both Wertham and EC in Commentary magazine that June (“The Study of Man: Paul, the Horror Comics, and Dr. Wertham”) seemingly summed things up: to the general public, results of any big debate over comic books and delinquency apparently ended in a draw. Link here.

Potentially serious PR blows, conservatives needed a high-profile public rebound.

And then conveniently, the “Brooklyn Thrill Killers” struck.

To Be Continued…