MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only and constitute fair use. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators and studios, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

Perhaps the best embodiment of the post-war comic book’s hardboiled tough guys would emerge at the very end of the classic film noir cycle, as comics were under intense social criticism and censorship. And it would come from a creator who was also a cop.

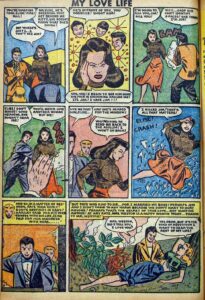

Brooklyn-born Peter A. Morisi was educated at the School of Industrial Art and the Cartoonists and Illustrators School in Manhattan. Although late to the game, he obviously loved the medium. In 1945, at age 17, he began as assistant on the newspaper strips Dickie Dare and The Saint. He’d just started at Fox Publications in 1948 when he was drafted into the Army, and even while stationed in Colorado in 1949, he still wrote and drew for their romance and crime comics such as My Love Life and Murder Incorporated.

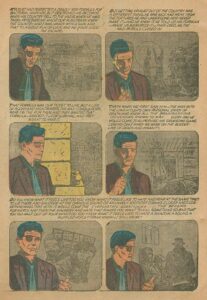

Tellingly, even his early romance stories showed a strong noirish flavor: “Love Was My Boss,” from My Love Life #6, includes the murder of the manipulative, narcissistic boss in question and the suicide of a psychotic femme fatale (who leaps from a skyscraper window) before the heroine finds her true love and contentment. Not exactly what you’d call a “meet cute.”

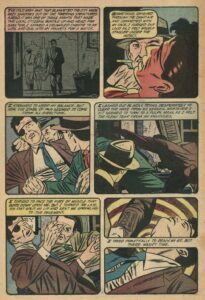

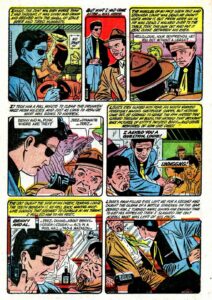

Discharged in 1950, Pete Morisi immediately freelanced at Harvey, Fiction House, Lev Gleeson, Quality, Comic Media and Marvel Comics forerunners Timely and Atlas, drawing westerns, romance, war, horror, and suspense, one-page fillers, anything and everything. His art was, comparatively speaking, never exactly exciting. Some might even say outright boring. Let’s be generous and simply call it “anti-dynamic.” It was also derivative, relying heavily on “swipes,” or copied and traced photo-reference. But he had a pitch-perfect sense of layout and design that caught the eye, drew you into the panels and told the story with a clear, quiet, economic intensity, regardless of subject matter.

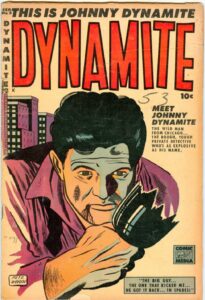

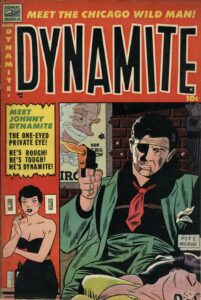

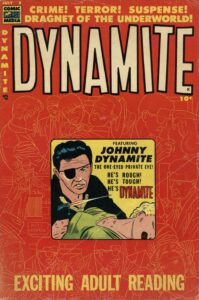

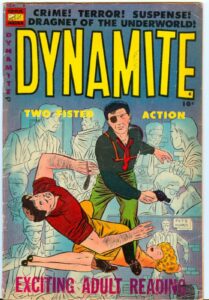

Then in Comic Media’s Dynamite #3, a 1953 anthology title normally devoted to tales of he-man adventure, everything seemingly clicked into place. Morisi launched a series, co-created with writer Ken Fitch, that was the ultimate expression of the nation’s then-current taste for noirish, violent, hardboiled crime procedurals. Called Johnny Dynamite, it was melodramatic, adult, shocking, and in many ways, graphically “modern” and sophisticated in its storytelling, and it would promptly dominate the book.

Johnny was a PI in the Mike Hammer mold, narrating his cases first-person as he took down underworld schemes with dogged persistence, ruthlessness, and a smoking .45 (even if that meant having to hunt and kill the dame that shot him in the head and left him with his trademark eyepatch in his second issue).

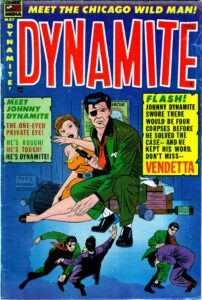

“The Chicago Wild Man,” as he was called, would slug, kick, and shoot his way through a series of very realistic cases, racking up an impressive body count as well as heavy personal damage and emotional regret. This was not a series for kids. This was Mickey Spillane delivered every month and in pictures.

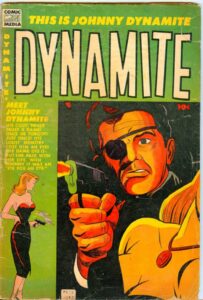

Comic Media folded in 1955, after sixteen Johnny Dynamite stories spread over six issues. The character was picked up and given his own book at Charlton Publications that year, where other hands began doing the stories before the series ceased publication completely…but not before one last Morisi tale, where presciently, Johnny Dynamite took a clandestine US government job helping French military forces in Viet Nam.

It was all just as well. By this time, like the blacklisted writers and directors of film noir, extreme violence and “inappropriate content” in comics came under severe public attack. Despite their wide adult readership, comic books were considered chiefly a children’s medium by civic-minded and reactionary political factions. Blamed for juvenile delinquency, subject to book burnings, Senate Committee hearings and, ultimately, industry self-censorship, crime as a comics genre, like the comics industry itself, would soon undergo a major collapse. Only a few companies survived.

In 1956, like the reversal of Dashiell Hammett, who began in law enforcement before turning to fiction, Pete Morisi achieved a childhood dream of joining the NYPD. Moonlighting wasn’t forbidden by the force, but Morisi took on the pseudonym “PAM” to avoid any possible conflicts with his day job, and continued drawing comics at home, nights, when he was off-duty.

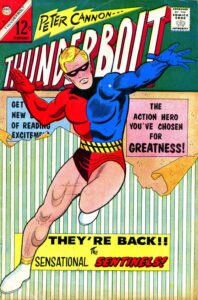

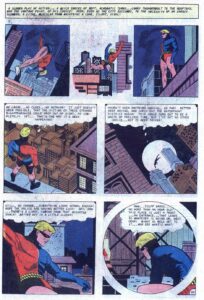

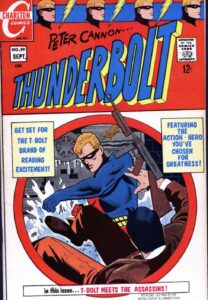

For Charlton comics in the 1960s, Morisi created the fondly remembered Peter Canon-Thunderbolt, a hero powered by Tibetan mysticism. Despite its metaphysics, the series still retained elements of mystery, noir, and crime procedural in its storytelling.

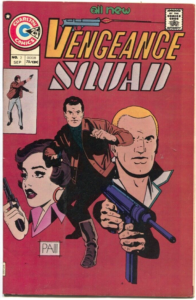

After patrolling Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan, and doubtless encountering much of the same criminality he’d written and drawn about, in 1976 Pete Morisi retired after 20 years with the NYPD. He’d continued his comic book career that entire time, working mostly for Charlton in multiple genres (westerns and supernatural were a specialty). Still, among his final work was the series Vengeance Squad, about a team of international mercenaries battling criminal cartels. He’d pass away in Staten Island in 2003, aged 75, a devotee of the medium to the end.

While never as famous a name as others in the field, his quiet, composed layouts, writing style and journeyman approach still carried an influence: industry legend Jim Steranko’s career-making run on the 1960s Marvel super-spy series Nick Fury Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. is arguably very much Johnny Dynamite brought into the space-age, right down to the attitude and eye-patch; even DC has attempted to bring back Peter Canon-Thunderbolt more than once. Peter Canon would also be one of the inspirations behind Marvel’s martial arts hero Iron Fist, and the DC super villain “Ozymandias” in Alan Moore’s impactful, award-winning graphic novel, film and television series Watchmen.

In more recent years, Johnny Dynamite has seen collected reprintings; the character has even been brought back as an occasional guest-star in various titles. And with the internet and social media now connecting us, new generations of readers have begun to discover and take appreciative notice of Pete Morisi’s work. Simultaneously, many old-time fans have also come to realize that we’d privately all been his admirers this whole time.