MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. The New Adventures of Charlie Chan are copyright DC Entertainment, Warner Bros. Global Brands and Franchises division of Warner Bros. Discovery and AT&T’s Warner Media, respectively. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

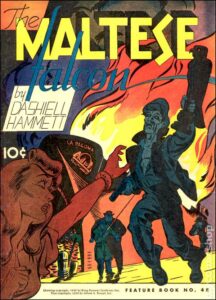

In 1946, David McKay Publications’ Feature Book, a title showcasing, naturally, only one feature per issue (and usually something from King Features Syndicate, like The Phantom, Mandrake the Magician, Dick Tracy or Blondie), decided to be on-trend by devoting its issue #48 to adapting The Maltese Falcon.

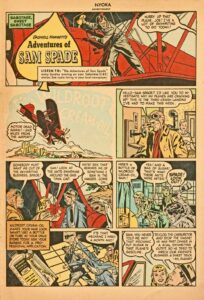

Surprisingly, this wasn’t based on the movie, but the actual Dashiell Hammett novel, right down to the burning of the La Paloma on the cover and referring to Joel Cairo as “the Levantine.” Complete in a single issue it shows, along with Classics Illustrated, how the concept of “graphic novels” in comics really isn’t anything new. Another comic strip version of the adventures of Sam Spade, meanwhile, could also be found in ads from his CBS radio show sponsor, Wildroot Hair Cream.

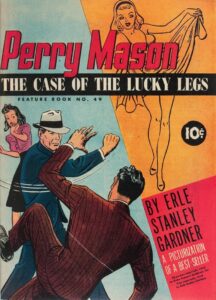

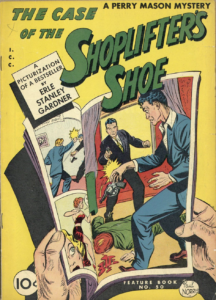

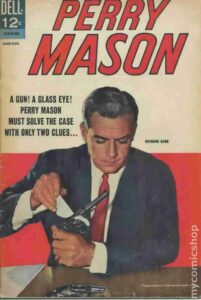

Next, Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason books were adapted in two issues of Dell’s 1946 Four Color Comics. Originally created back in 1933, the famous defense attorney would do slightly better in later newspaper comic strips (1950-52) plus two additional comic books in 1964 (for the TV show), alongside all his novels, movies, radio, television, television & television again.

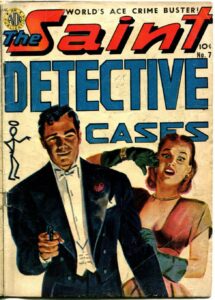

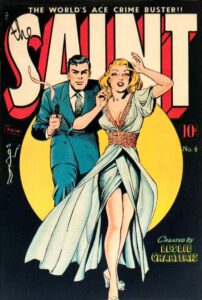

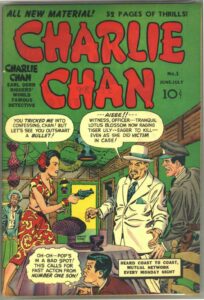

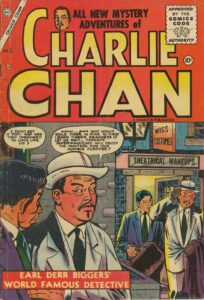

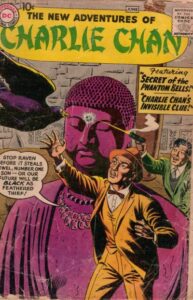

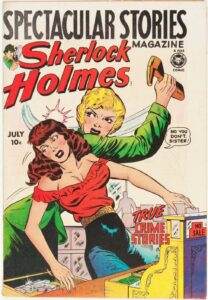

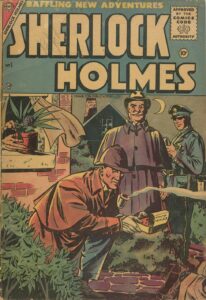

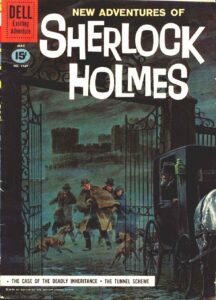

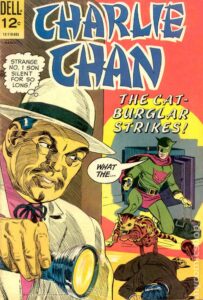

From 1947 until 1952, Leslie Charteris’ The Saint also had his own title, published by Avon Comics concurrently with a daily comic strip starting in 1948 and lasting until 1961. Then Charlie Chan returned with Harvey Comics in 1948, featuring stories by the famous team of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, creators of Captain America, plus art assistance from the talented Mort Meskin and others. Charlie Chan returned again in 1955 with Charlton, and again in 1958 with DC. Sherlock Holmes, bless him, would always seemingly skip from publisher to publisher, as if appearing in differing guises as needed, but never gone for long.

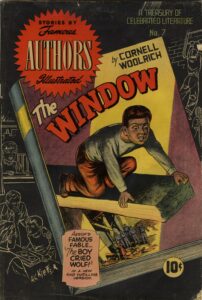

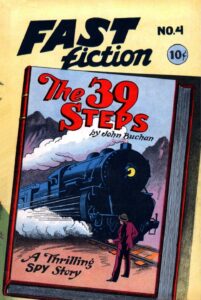

By 1950, with the film noir era in full swing, perhaps it’s not surprising that even Cornell Woolrich would find himself in a comic book. That’s not something I ever thought I’d say, but there it is: Woolrich’s The Window, in Famous Authors #7 from Seaboard Publications. Seaboard attempted to compete with Classics Illustrated in the highbrow comics arena, only to ever produce the one series. But over its 12-issue run, Famous Authors, originally titled Fast Fiction, also managed to include adaptions of John Buchan’s The 39 Steps (#4) and George DuMaurier’s Trilby (#12, as La Svengali). So clearly, their dark hearts were in the right place.

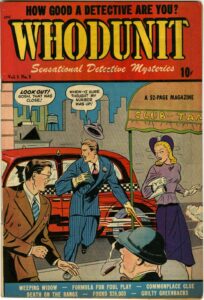

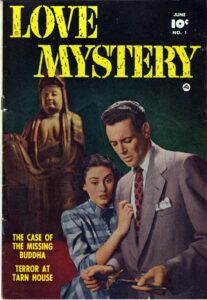

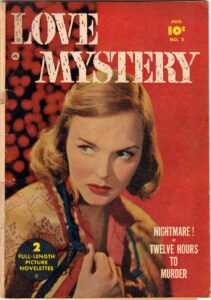

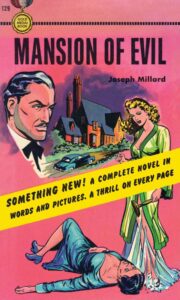

The classic mystery form was also showcased in this period, as comics like 1948’s Whodunit? told short stories scattered with clues so the reader could guess the culprit before the last page, and 1950’s Love Mystery from Fawcett, which added spice to the popular romance genre, cranking up the heroine’s stakes with longer stories and more danger, suspense and McGuffins. That year, Fawcett would also experiment combining a full-color comic with their Gold Medal paperback line: Mansion of Evil, by author Joe Millard, a contemporary, somewhat Gothic suspense-murder mystery with a romantic subplot and lovely artwork, like having a Hitchcock movie you can carry in your pocket. The format ultimately failed, but it left us with another fascinating, early graphic novel far ahead of its time.

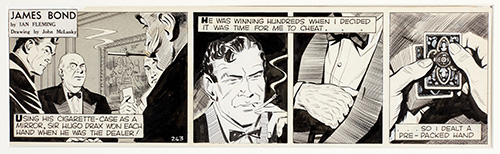

By the mid-1950’s, crime and mystery-horror comic books became neutered, pilloried by the public, then censored and reduced to kiddie entertainment by national “clean-up” campaigns. Hardboiled and noir retreated into paperbacks and television (Mike Hammer, The Untouchables, Peter Gunn), traditional mystery returned to novels, a few magazines and the occasional newspaper strip (notably in 1957: Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe (US) and Ian Fleming’s James Bond (UK), whose look by artist John McLusky influenced the casting of the first movie).

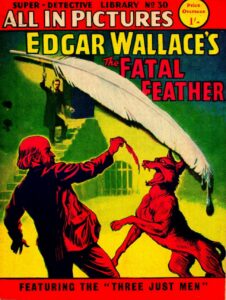

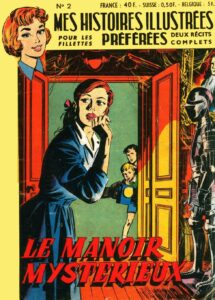

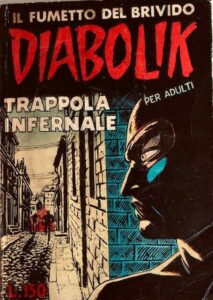

But by now comics and traditional crime and mystery fiction had also developed internationally, of course, and noir took hold in post-war Europe, Latin America, and Asia. The impact could be felt when Edgar Wallace, Leslie Charteris, Graham Greene, and John Creasey were adapted into Super Detective Library (Great Britain), or in thriller revistas like El Daga Roja and Dos Americanos en Europa (Spain), the YA atmospherics found in Schoolgirls Picture Library (GB) and it’s continental version Mes Histoires Illustrees (France), or even in the Edogowa Rampo-psychodrama vibes running through manga like Sabu to Ichi Torimono Hikae (Detective Stories of Sabu and Ichi, Japan). It’s also there in dark anti-hero comics like Diabolik (Italy), the eternally recurring villain Fantomas (France, Latin America), and Golgo 13 (Japan).

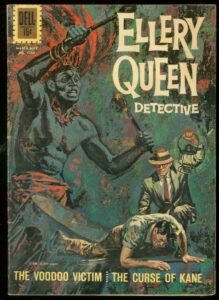

Meanwhile however, in 1960s America, television gave Dell-Western (and Western’s new independent label, Gold Key) the chance to go licensing-crazy and bring traditional crime and mystery back. Alongside reboots of Sherlock Holmes, Ellery Queen, and Charlie Chan, most of the era’s TV crime shows, including those based on novels, got a shot at comic stardom, or at least a tryout in Dell’s Four Color title.

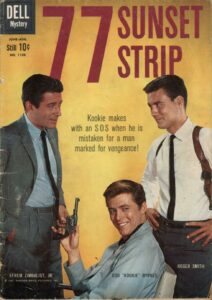

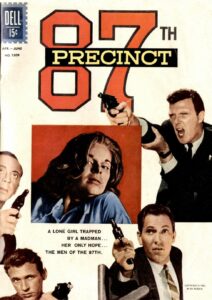

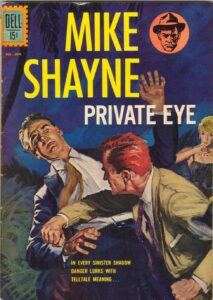

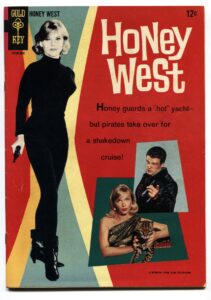

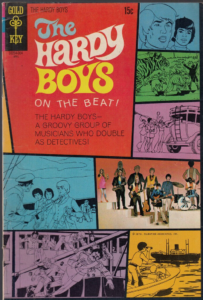

Imagine it: Roy Huggins’ 77 Sunset Strip (1960), Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct, Brett Halliday’s Mike Shayne Private Eye (both 1963), Erle Gardner’s Perry Mason (1964), G.G. (aka, Gloria & Forest) Fickling’s Honey West (1966), even the Hanna-Barbera Hardy Boys cartoon (1970 & 1972) and more. Well, now you didn’t have to. All were available at your local drugstore, between 12 and 25 cents, in full color.

Sadly, it took a long while before some of the genre’s most famous names made the list. Nancy Drew, who began in 1930, was created by publisher Ed Stratemeyer as the female counterpart to his popular Hardy Boys series and written by several authors as “Caroline Keene.” She generated 175 novels, films, merchandise from the 1950s to the 1970s, TV shows and even multiple video games before entering comic books. It wasn’t until the 21st century that she’d team up with the Hardy Boys for a dark, hardboiled noir take on her character in 2017, which probably did the plucky miss no favors, plus a 2019 solo series and a 2020 sequel.

Agatha Christie, the “Queen of Crime,” is also sadly underrepresented in comics. Despite the notion of a Hercule Poirot or a Jane Marple being perfect for crime and mystery comics since at least the 1930s, Christie’s work wouldn’t be adapted until the beginning of the 1990s, in a series of high-quality French bande desinee graphic novels (and their 2002 English translations from Harper Collins). They’re gorgeous and highly recommended, especially the French language originals, so better late than never.

Still, considering she’s third Most Published in the world after the Bible and Shakespeare…well, as Philo Vance was known to put it: “C’est plus qu’un crime; c’est une faute.” (“It is worse than a crime; it is a blunder.”)

To Be Continued…