MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only and constitute fair use. Any and all artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators and companies, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

Today she is known for a long career that includes the classic crime thrillers Strangers on a Train (1950), The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) and its four sequels, the million-selling The Price of Salt (about a lesbian relationship with semi-autobiographical elements and written in 1951 under a pseudonym) plus a 1991 nomination for the Nobel Prize in Literature. More unknown is Patricia Highsmith’s early years supporting herself as a comic book scriptwriter, the only long-term employment she ever had prior to becoming a novelist. That she deliberately sought to erase them from her record says a lot about the status comic books held in society at the time as disposable entertainment, despite their popularity.

Born in 1921, in her maternal grandmother’s boarding house in Fort Worth, Texas, Mary Patricia Plangman was the child of artists Jay Bernard Plangman and Mary Coates, who divorced ten days before their daughter’s birth. Her mother re-married in 1924, to artist Stanley Highsmith. Her grandmother taught her to read at an early age and the child soon poured through the woman’s extensive library. This no-doubt helped young Patricia deal with an intense, chaotic homelife; according to Highsmith, her mother told her at one point she’d tried to abort her by drinking turpentine (though another biography indicates Jay Plangman tried to persuade Mary to have an abortion, which she refused). Patricia would forever have a complicated relationship with her mother and was largely resentful of her adoptive stepfather.

In 1927, the Highsmiths moved to New York City. At eight, Patricia discovered a copy of Karl Menninger’s The Human Mind, and became fascinated by its case studies of mental disorders such as pyromania and schizophrenia. At 12, Patricia was taken back to Fort Worth to live with her grandmother. Left feeling abandoned by her mother, she’d call this the “saddest year” of her life.

She returned to live with her parents in New York, primarily in Manhattan but also in Queens. A lifelong diarist, she developed her writing style as a child and often coped with circumstances by writing entries that fantasized her neighbors as murderous personalities with psychological problems behind their normal facades, themes she’d later explore extensively in her novels. In 1942 Patricia Highsmith graduated from Barnard College, where she studied English composition, playwriting, and the short story.

Now looking for a job — any job with a literary bent, please! — she answered an ad for “reporter/rewrite”. She found herself at the offices of Ned Pines, of the Sangor-Pines “shop,” and the Nedor-Standard-Pines association of comic book publishers. Quite a step down for a recently graduated Lit Major, but young Pat rolled up her sleeves and got to work.

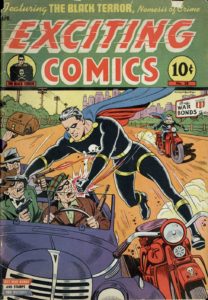

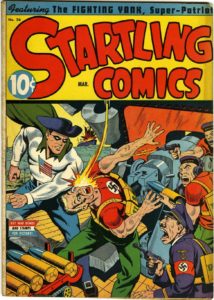

From 1942 to 1943, working in a bullpen with four artists and three other writers, creating two comic book scripts a day for $55-a-week paychecks, Highsmith began cranking out the adventures of Sgt. Bill King and the company’s resident costumed superheroes The Fighting Yank and The Black Terror, plus other back-up features and fillers long since lost to time.

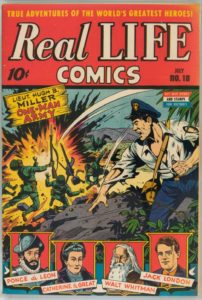

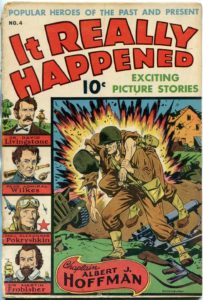

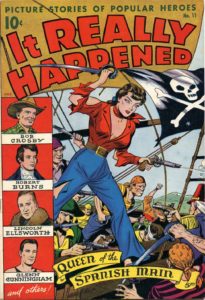

Quickly realizing she could make more money working for other companies as well, she began freelancing around the industry. For Real Heroes, It Really Happened and True Comics, she wrote comic book biographies of Einstein, Galileo, NYC mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, Oliver Cromwell, Catherine the Great, David Livingston and many others. Showing a flair for wartime aviation tales, she also added Hillman Publication’s Airboy Comics and its supernatural-monster character, The Heap, to her client list.

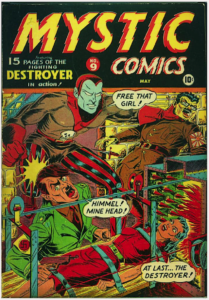

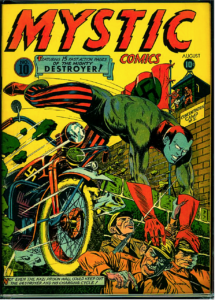

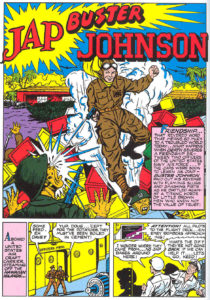

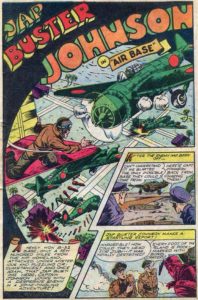

Simultaneously, from 1943 through 1946, she’d contribute to Timely Publications, Marvel Comics’ early incarnation, providing stories for their wartime heroes The Destroyer (a grim super-commando dressed in a harlequin costume with a skull symbol on his torso) in Mystic Comics, and the even more self-explanatory exploits of Jap-Buster Johnson in USA Comics.

The racism in some of these stories is shockingly “of its time” and, perhaps influenced by wartime propaganda and Highsmith’s early Texas upbringing, not entirely surprising. Over the course of her career, some of her prejudices and more conservative opinions would often come as a shock.

(An interesting sidenote from this period: Timely editor Vince Fago, on his 88th birthday, still remembered Pat Highsmith as “a beauty… just amazing, a terrific looker.” But as Vince was newly and happily married when Pat came to work for him, he thought he’d introduce her to a young editor whose post he’d taken for the duration of the war. That young editor was Stan Lee, at the time a soldier back in NYC on leave from the U.S. Army. Fago took Stan up to Pat’s apartment “near Sutton Place” hoping to make a “match”. But the future creator of the talented Mr. Ripley and the future co-creator of Spider Man did not exactly hit it off. “Stan Lee,” said Fago, “was only interested in Stan Lee.” Pat, meanwhile, wasn’t quite admitting what her sexual interests were at the time. Stan, years later, claimed failing memory and “murky mind” about the incident, and would remember only Pat’s name.)

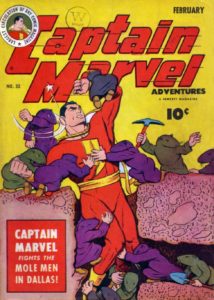

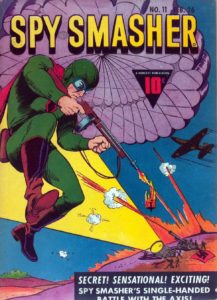

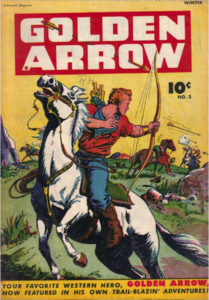

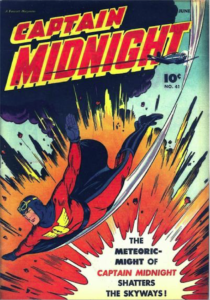

From 1943 to 1948, she also wrote for Fawcett Publications, home of the popular Captain Marvel (known today as Shazam!), and scripting for such characters as Golden Arrow, Spy Smasher, Captain Midnight, Crisco and Jasper, plus Western Comics as well as some romance stories. Late into the decade, Pat would also begin working there as an editor, taking over the job from departing editor Stanley Kauffmann. By this point, she had become a true fixture within the industry. “She had a drive for perfection,” according to Everett Kinstler, who penciled for Fawcett’s Motion Picture Comics at the time, and himself would go on to paint the official presidential portraits of Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan.

“My work [in comics] had nothing to do with literature, but it did stimulate my imagination,” Pat would later write. Patricia Highsmith’s comic book efforts also allowed her to pursue her independent writing career, helped finance her Greenwich Village apartment and lifestyle and even afforded her a year living in Mexico. During this time, her short story “The Heroine” would emerge in Harper’s Bazaar and earn her the O. Henry Award for best publication of a first story in 1946.

Working at the Yaddo writer’s colony in Sarasota Springs NY, and rewritten at the suggestion of Truman Capote, her first novel Strangers on a Train would see print in 1950. The book contained the violence that would become her trademark, and that she had certainly been refining in her work over the previous decade. It would prove a modest success, earning her the Edgar Award nomination for Best First Novel. But it’s Alfred Hitchcock film adaptation in 1951 that would truly propel Highsmith’s career and reputation as a new, gifted writer of dark, ironic psychological thrillers. Her 1955 novel The Talented Mr. Ripley would cement it. (Plus win her the Edgar Award in 1956, and France’s Grand Prix de Literature Policière in 1957.) Many more awards, novels, stories, film adaptations, sales and accolades would follow over the decades, until her passing in 1995 at age 74 from cancer, in Locarno, Switzerland…an American success story of another kind.

Although she sought to erase any mention of her early comic book career from her resume, destroying most records of her time there (and making it difficult to identify all that she wrote, a yet-ongoing bit of literary archaeology), she would still occasionally use the names of some of her industry coworkers in her writing (these included editor Dorothy Woolfolk, under her maiden name of Roubicek, and noted inker Joe Sinnott). Some observers have seen Highsmith’s character Ripley, and the heroic inner projections he imagines as he schemes and improvises his chameleon-like crimes, as her alter ego whose actions vaguely parallel her time spent in the comic book business.

And in a way, it is Tom Ripley’s very first victim, of tax scam, in The Talented Mr. Ripley who becomes the parting gesture to her former career: “Tom had a hunch about Reddington. He was a comic-book artist. He probably didn’t know whether he was coming or going.”

Patricia Highsmith wasn’t the first author, nor the last, to make the jump into crime fiction from comic books, of course. And her approach to the crime and suspense genre could be seen as a herald of things to come. Despite victory parades, joy and celebrations of the post-WWII years, a type of hardboiled crime, but approached with a psychologically darker and more ruthless, bitter edge, had evolved on film and the literary scene. Ever the cultural barometer, comic books also quickly began to reflect and embrace this new world of noir.

BONUS! Download a PDF of some of Patricia Highsmith’s early Public Domain comic book work by clicking HERE.

To Be Continued…