MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only and constitute fair use. Any and all artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators and companies, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

By WWII, the red threads on the Evidence Board connecting crime and comic books began touching international suspense more often. With the need to defend democracy, those early lady crime busters who had emerged in the first years of comics—the girl reporters, investigators, and masked vigilantes—began morphing into full-fledged women warriors.

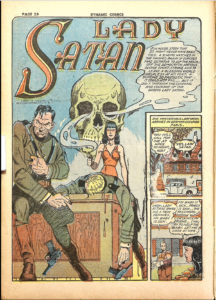

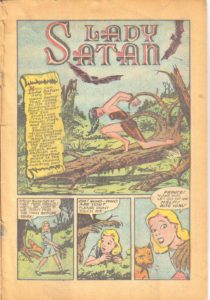

Heroines like Wonder Woman could, of course, be expected to flex their powers on the Axis war machine almost at once. But from the ranks of early wartime heroines who lacked indestructability, flight, or superhuman strength, there could also be found Lady Satan (1941-48), who seduced and assassinated Nazis across occupied France to avenge her dead fiancé, then by her third appearance became an all-powerful sorceress battling occult menaces, and all while being infrequently published by the Harry “A” Chesler shop in Dynamic Comics, Red Seal Comics, and other titles.

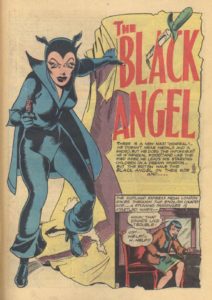

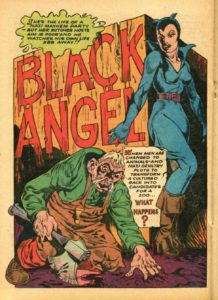

Another was Black Angel in Air Fighters Comics from 1942-45 (Hillman Publications, created by John Cassone): Sylvia Manners, a frail and delicate English Rose living in her family’s castle and caretaking for a worried aunt, who’d also double as a deadly fighter pilot and spy. (And apparent Mistress of the Cheesecake Arts, in buccaneer boots and a slinky, black aviatrix costume. One could almost feel the male gaze emanating from her artwork.)

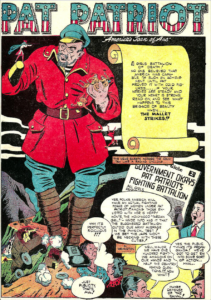

A bit more Proletarian and no-nonsense was Pat Patriot, in the 1941 Daredevil Comics, published by the lads from Crime Does Not Pay, Lev Gleeson, Charles Biro & Bob Wood. Pat was a defense industry worker turned national spokeswoman, selling war bonds and performing in USO shows, who donned an American flag-based blouse and skirt to battle spies and saboteurs, and would later lead a volunteer, all-girl commando unit called the Death Battalion into the war proper.

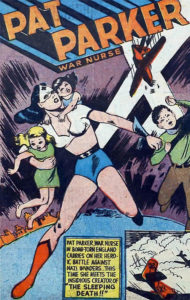

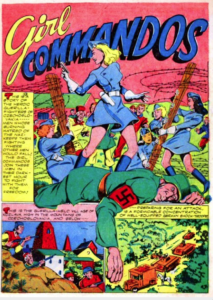

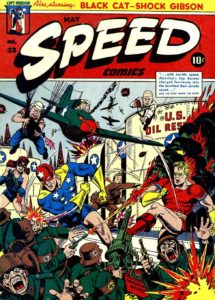

Meanwhile, tiring of her medical career and wanting to do more, Pat Parker War Nurse (1941) donned an even skimpier costume, plus a mask to shun publicity. Like the other Pat, she had no superpowers, just bravery and patriotic zeal (and, it turns out, deadly capabilities) to aid in the global fight against the Axis. She’d eventually create another all-girl group of bloodthirsty international freedom-fighters called the Girl Commandos and battle her way through 37 issues of Speed Comics from Harvey Publications, sharing magazine space with the crimefighting Black Cat, slaughtering Nazis and Japanese by the score.

And all this fierce motivation wasn’t just relegated to fiction. While there had been individual standout female creators in comics, WWII represented real breakout opportunities for women in the field. At the time, comic books represented almost a quarter of the overall American reading market, moving millions of units a month, and 30% of all reading material shipped to deployed troops overseas were comic books. As men were called up for the draft, women began filling the void left in the comics workforce, stepping in to help carry the industry through its war years and beyond. And where men had often created the series and characters, now female writers and artists began expressing themselves in what were often recognized as traditionally “masculine” genres. These included hardboiled crime and mystery stories, the ubiquitous superhero, action and adventure tales, as well as war strips. And women in the field wrote and drew such material “strong” enough that readers couldn’t tell the difference.

Pat Parker’s adventures, for instance, appear to have been drawn primarily by women (one of whom, Barbara Hall, also drew The Black Cat and lady reporter The Blonde Bomber). “Appear” is the correct word, since in the grindhouse of the early comic book industry, many features weren’t signed or were attributed to a masculine pseudonym. But old accounting ledgers reveal the truth, and the various women contributors to the field. These include Toni Blum (writer for the Eisner & Iger Shop), Ruth Roche (business partner with Iger, also writer of Phantom Lady at Fox Publications) and Virginia Hubbell (ghostwriter for Charles Biro at Crime Does Not Pay), among many others.

For some this was a paycheck, but for others this was a launching pad.

Lily Renee Wilheim was born in Vienna, Austria, of well-to-do Jewish parents. As a child, she often drew as a hobby, under the family’s dining room table, sketching ballerinas and costumed performers she’d seen at the theater. Her father worked for a transatlantic steamship line, helping her escape the Anschluss, the Nazi annexation of Austria, and thus the Holocaust, by Kindertransport in 1938. At 14, after a tough year alone in Britain, she was able to rejoin her parents who had relocated to New York City in 1940, living in a rooming house on the Upper West Side.

She began going to night school while taking art jobs to help support her family, painting wooden boxes and doing illustrations for Woolworth’s catalogues. Her mother saw a newspaper ad for comic book artists, and armed with a drawing of Tarzan and Jane she had made, Lily soon found herself working for Fiction House, publishers of Sheena Queen of the Jungle comics and others. Fiction House titles catered to an overall male demographic, with heavy reliance on glamorous cheesecake heroines and rugged he-men heroes and tended to a slightly higher quality of illustration (mostly thanks to contributions from the always reliable Eisner-Iger studio shop).

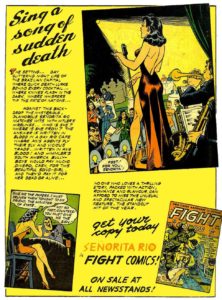

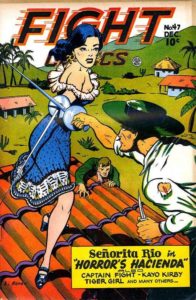

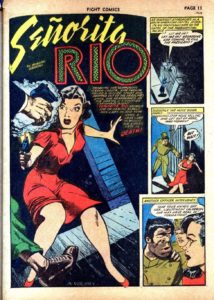

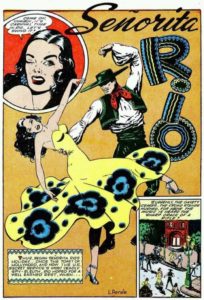

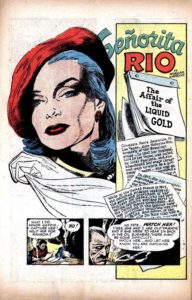

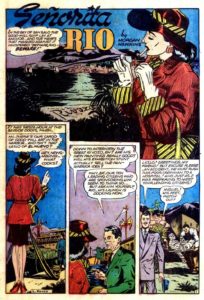

At Fiction House, as “Lily Renee,” she drew the female fighter pilot Jane Martin for Wings Comics from 1943 – 1944, and the gothic horror series Werewolf Hunter for Rangers Comics from 1943 -1948. But she would ultimately distinguish herself at the company for her standout contribution to the international espionage strip Rio Rita, originally created by Nick Cardy in Fight Comics. Rita was American comics’ first Latina heroine, a beautiful movie star and spy who battled Nazi agents and their allies in South America. This channeled Lily’s own desire to fight the fascist powers. “I could live out a fantasy, if only on paper,” Renee later told an interviewer. “It was a form of revenge.” The series ran until 1947.

Lily Renee always considered herself an artist first and foremost, however, and drawing comic books was not necessarily looked on as a proper profession. After the war, and time spent drawing romance titles like Teen-Age Diary Secrets and humorous series such as Abbott and Costello Comics in the 1950s, Renee became a freelance commercial artist, jewelry and textile designer, took writing courses with Phillip Roth, wrote plays (one produced by NYC’s Hunter College) and children’s books and even befriended photographer Diane Arbus. She was also married to Randolph Phillips, a political activist who directed the ACLU’s national committee of conscientious objectors in the 1940s and was chairman of the National Committee for Impeachment in 1972, with whom she had two children. Living over 40 years on Madison Avenue, actively drawing and painting until the end of her life, Lily Renee passed away in New York City at the age of 101 on August 24, 2022, a truly American success story.

To Be Continued…