MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. Brenda Starr, Reporter is copyright the Tribune Entertainment Co. and Tribune Content Agency. Lady Danger, Gangbusters and “Lady Cop” are copyright DC Entertainment, Warner Bros. Global Brands and Franchises division of Warner Bros. Discovery and AT&T’s Warner Media, respectively. Any and all other artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

[WARNING: Contains explicit imagery.]

The first actual, real-life lady detective appeared in America in 1856, when Kate Warne was hired as an undercover operative for the Pinkerton Detective Agency (the first woman detective at Scotland Yard, btw, wouldn’t come about until 1919). Warne’s exciting and dangerous career included solving major railroad thefts, capturing bail-jumpers, breaking a Confederate spy ring in Washington D.C. and even helping to thwart an assassination attempt on the life of Abraham Lincoln in Baltimore. She would eventually supervise an entire bureau of female operatives for the famous agency, until her death in 1868 at the young age of thirty-five. A grateful Alan Pinkerton would memorialize her in his published memoirs and popular casebooks, and even have her buried in his own family’s cemetery plot.

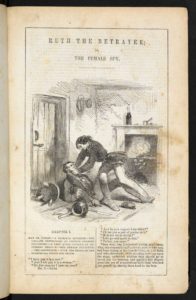

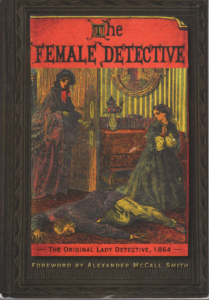

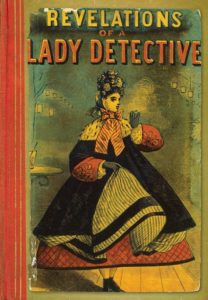

Thanks to operatives such as Kate Warne, the idea of woman investigators captured the public imagination early. By 1862, crime fiction’s first professional lady sleuth appeared in Ruth the Betrayer; or, The Female Spy (if by sleuth one means police informant, brothel madam and stone killer, although Ruth is referred to as a “detective” in the text), to be followed by two others over the next two years: 1863’s The Female Detective and Revelations of a Female Detective in 1864. In the ensuing decades many more would follow, globally as well as from Great Britain and the US. And so, a mystery sub-genre was born. It would come to include many famous characters over the years, from Jane Marple, Beatrice Bradley, Nancy Drew and Bertha Cool right through to Modesty Blaise, V.I. Warshawski, Agatha Raisin, Lisbeth Salander and Precious Ramotswe. It would also move across all mediums, from the penny dreadful and nickel weekly to novels, pulps, radio, film and TV.

Which brings us around again to comics. And back to their shady origins.

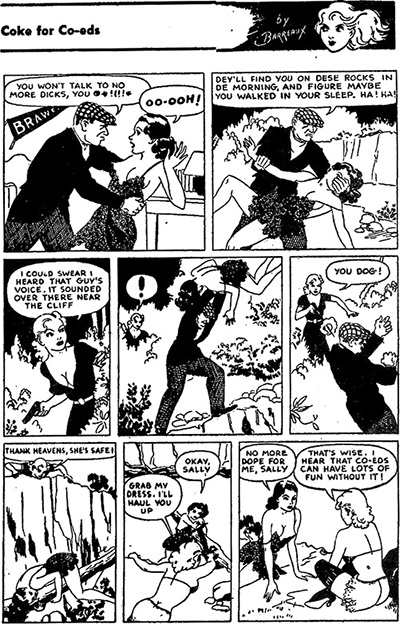

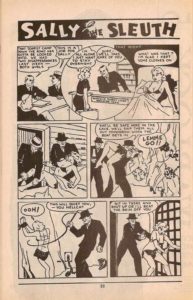

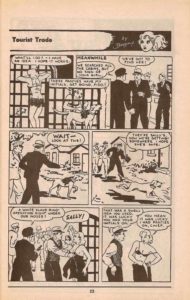

Until another is found, the earliest woman detective in the comic book format is very probably, and by now not surprisingly, Al Barreaux’s Sally the Sleuth, which began in 1934 as an “adult erotic” filler feature in the sleazy, pornographic pulp Spicy Detective Stories. Which means we can add one more first to this noted African-American cartoonist’s resume, along with the first superhuman comic character (Olga Mesmer, Girl with the X-Ray Eyes) and the first comics packaging-agency “shop” (Majestic Studios).

He may not have been thinking too much about trailblazing, however. Sally was strictly commercial, and her adventures tended to be written with a touch of burlesque humor to go along with the sleuthing and nipple-slips so in keeping with the “Spicy” brand. The crimes may have been the typical sadism and brutality, but the dialogue was pure Jazz Age, tongue-in-cheek flip. And Sally was no iconic sexual revolutionary. As an operative, very often she’d stumble onto the facts of the case by accident, resolving things only after a nude pratfall and glib remarks, at which point her male police pals would usually arrive in time to rescue her with a smirk and let her borrow their jacket.

Still, I guess a girl’s gotta start somewhere, and the character did evolve into a more determined, smarter investigator over the decades as she made the shift from the grime of “under the counter” pulps into legitimate, mainstream comic books. And in the comic publishing business, one didn’t argue with success: Sally the Sleuth, in one form or another, lasted until 1954, chalking up an impressive twenty-year run.

But even before all that, the earliest crime comics to feature serious independent female headliners could be found in the subgenre of “fearless girl reporter” strips that began in newspaper comics of the 1920s, then moved to comic book titles almost from their beginning in the mid-1930s. These series usually showcased single newspaper women, focused on finding the truth and usually fed up with the incompetence and inaction of shallow male editors, fellow reporters or cop boyfriends, and who set out to solve the crime, save the community, show their worth, get ahead in their careers, and then go forward with their lives.

Their dialogue may often mimic the snappy, sarcastic patter of screwball movies like The Front Page or the Torchy Blaine series (Superman’s creators claimed they based girl reporter Lois Lane on actress Glenda Farrell’s Torchy character), and they all seem to share a taste for the same red dress, but their character motivations reflect pure professionalism, strength and equality, even downright superiority, over and again. They take chances the silly men surrounding them never would, they uncover the truth and they get the story. That they make time for dreams of romance or self-care merely shows how much more emotionally balanced they really are. In between shoot-outs, that is.

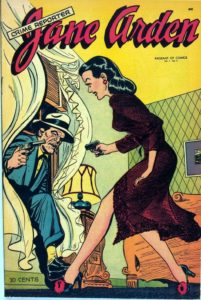

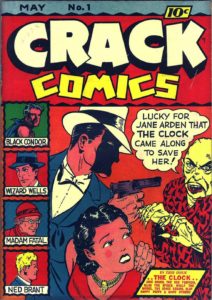

The prototype is undoubtably the comic strip adventures of Jane Arden, which began in November 1928 and ran in Register and Tribune Syndicate papers until January 1968, a startling forty-year run. Created by writer Monte Barrett and artist Frank Elllis, Jane was a gal never content to just report on crime when she could go undercover and expose crooked activities herself firsthand, regardless of the danger.

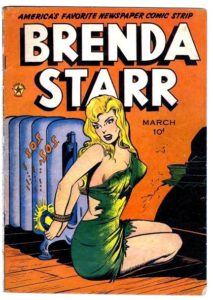

Once Jane Arden was established, the concept proved so popular that she became the template, and imitated ever since. Soon, she’d inspire other similar lady newshounds in the funnies, including the popular and long-running Brenda Starr, Reporter (1940) and (despite what the creators have said) having a clear influence on Superman’s pal Lois Lane. Jane Arden was also one of the first American comic strip characters to get involved with World War II, taking on a war assignment immediately after the outbreak in Europe, exposing Nazi infiltration into a fictional, neutral Balkan kingdom called Anderia.

While only ever a moderate success in the US, her strip was widely popular in Canada, the UK, Australia and Europe, which in turn made Jane Arden commercial enough to generate a 1938 radio show, a 1939 movie from Warner Bros. and reprintings in comic books from various companies until 1948 in the US, and 1956 in Australia. Additionally, her Sunday strips would feature cut-out paper dolls for her readers.

The character’s influence would also extend to real life: Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Mary McGrory credited Jane Arden with inspiring her career in journalism. (Considering the fearless and contentious coverage she gave to the Joe McCarthy Hearings, the Vietnam War and Watergate, there’s something to be said for Jane Arden’s ethics being one reason behind McGrory landing on Richard Nixon’s “Enemies List.”)

The Depression years had clearly hardened everyone up, and the decade had ended with a fresh, new type of series character established in the media landscape: the feisty, wisecracking, independent “tough cookie” who could hold her own with men in a “Man’s World.” Replicated and proven marketable in newspapers, radio, on stage and in the movies, yet another sub-genre was born, and comic books leapt to include it in their roster of archetypes, alongside the detectives, cowboys, magicians, explorers and comedy strips.

By 1940, everything was in place: comic books were now a proven medium, Harry Donenfeld—flush with cash from Superman and Batman and holding a lock on most distribution—began loaning money to young start-up publishers in need of content, an industry was established, hungry talent was cheaply available, and readers old and young were looking for new ways to experience their favorite story tropes along with the new superhero phenomena. The floodgates opened… and brought these “modern dames” with them.

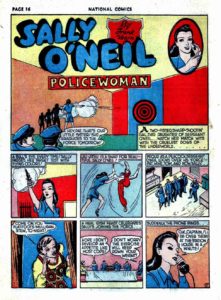

That year, there was an explosion, not just in superheroes, but in strong, self-determined heroines. From law enforcement came Patty O’Day, Penny Wright, Sally O’Neil, Police Woman and gun toting, jiu-jitsu fighting DA Betty Bates, Lady-At-Law (who lasted until 1950). From the front lines came Jane Martin, War Nurse (and fighting lady pilot).

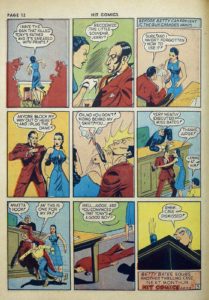

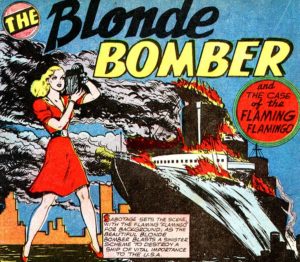

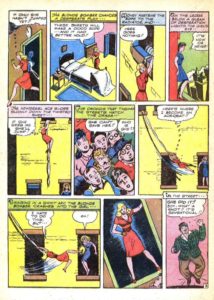

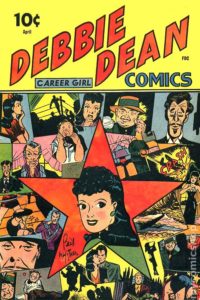

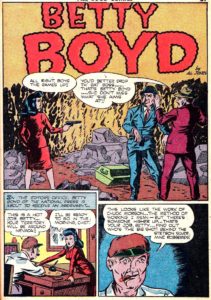

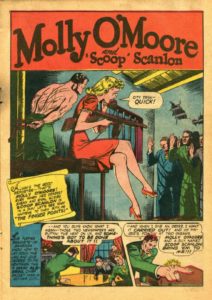

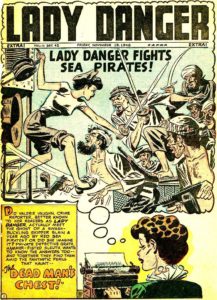

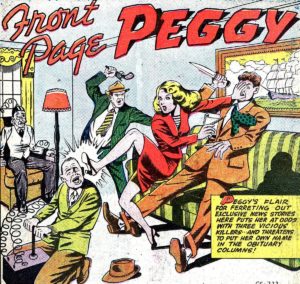

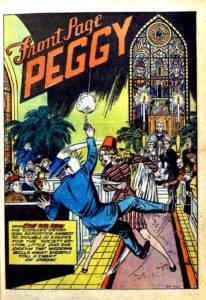

And, of course, as the decade rolled on, there followed a parade of two-fisted lady reporters: Fran Frazer in 1941; The Blonde Bomber and Debbie Dean, Career Girl (another newspaper strip reprinted in comic books) by 1942; Betty Boyd, Gail Porter and Joan Mason (solo from her regular gig as a supporting cast member of The Blue Beetle series) in 1944; Linda Lens and Molly O’Moore in ’45; Lucky Wings, Lady Danger and Front Page Peggy in ’46; Lucky Dale in ’47.

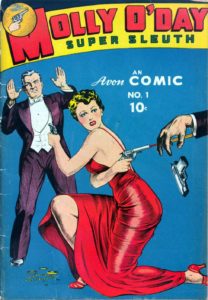

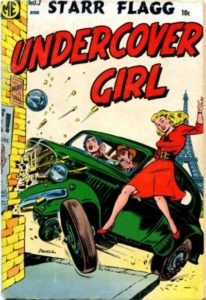

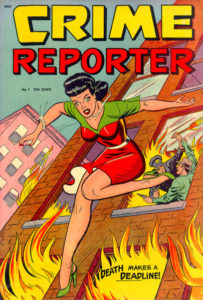

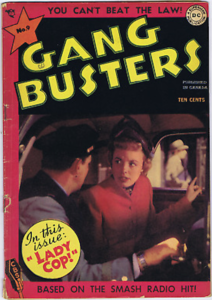

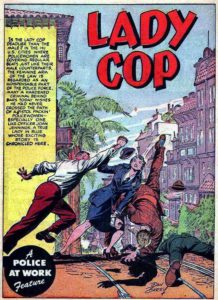

And let’s not forget Senorita Rio, movie star and deadly international spy (1942); Jill Trent, Science Sleuth, solving crimes with her inventions and her mind as well as her guns and her scrappy partner Daisy (beginning in 1943); homicide detective Molly O’Day, Super Sleuth (1945); or Starr Flagg, Undercover Girl (1947-55). By 1948, Joan Mason would be back again, this time headlining the title Crime Reporter, and even Brenda Starr from the newspapers would get her own comic book (albeit with a decidedly different style of presentation). In 1949, DC’s Gangbusters would capitalize on Crime Does Not Pay’s “true crime” civil mindedness with Lady Cop.

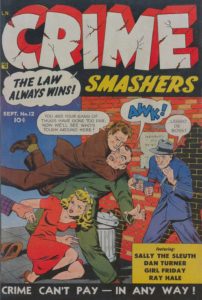

By the time 1950 rolled around, and as crime comics and public moral outrage were both in full swing, things began to come full circle as good ol’ Sally the Sleuth—now keeping her clothes on—returned to join undercover policewoman Gail Ford, Girl Friday and even Robert Leslie Bellum’s Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective in the comic book Crime Smashers.

These aren’t the only examples, of course. And one can’t say they were entirely free from problematic and patronizing attitudes of the day (not to mention bad writing and poor art).

But these characters also represent the emergence of something different: a progressive, developmental step in a powerful, very positive direction. There would be dozens more. And for every woman in the medium shown protecting society and the world, fighting equally alongside men and doing them one better, there would also be the Bad Girls: the gun molls, gang debs, crooks and killers who stood with those against the law. They too had their own showcase in the comics.

Yet even before the spotlight would shine on them, there emerged yet another group of lethal females. Dangerous ladies that would don the mask, hiding their identities behind mysterious alter egos to descend into the underworld and meet it on its own terms…

To Be Continued…