MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only, and constitute fair use. Any and all artworks in this series of articles are public domain, and/or copyright their respective creators, unless otherwise noted.)

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

In comic book history, female representation and equality can seem problematic. In crime, mystery and superhero comics especially, the question of sexism is a bit of a moving target, even today. In one sense, yes, women have been objectified terribly since the early days of comics, portrayed as mere eye-candy and candidates for victimhood (let’s not forget the comic industry’s roots stemming from pornographers and hard-boiled pulp fiction, co-opted by more and more sensationalized horror and sleaze). Scatter-brained extensions to the heroic male protagonist, the ladies were frequently there to stumble into trouble and be rescued, framed as nuisances and referred to as “trouble,” recipients of dark misogynistic violence and weird menace. There because creaky literary traditions and genre formulas demanded it.

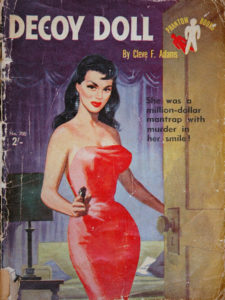

But there also exists the modern Feminist theory argument that frames hardboiled/noir’s (and, by extension, comic books’) femme fatales, con women, gun molls, pin-up girls and burlesque queens as self-empowered icons, using their savvy sexuality—and potentially homicidal impulses—against the era’s sexist patriarchy. Whole subgenres of crime novels are devoted to the idea, including Gone Girl and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, stretching all the way back through various post-war pulps and paperbacks, perhaps including Gypsy Rose Lee’s The G-String Murders and certainly much, much earlier. Since at least the 1920s, and despite wholesome Nancy Drews and cozy Jane Marples around leading the pack, intelligent and independent women were frequently defined within the genre by only possessing a challenging, dangerous and sometimes lethal sexuality. The “looks that kill.”

And it’s true: there’s just not that many positive, un-sexualized women characters connecting the crime genre and comic books, sadly. From the first, it was mostly a male-driven business and the boys tended to suck up all the air in the room. Male characters, created by male imaginations and tailored for a male readership, hogged the spotlight. Like much else in the field, women became (adolescent, it must be said) male power-fantasy projections. Objects to fear, worship and ultimately define and control. Even when the history of comics began to be dissembled and analyzed, it was often seen from a male perspective.

Second: the art tends to get in the way. Focusing as it does on idealizing comic characters to make them more commercially viable, heroes are drawn more outwardly handsome, heroines more overly attractive and villains more obviously vile. Caricature was always the visual shorthand for a medium built to get its point across faster, and physical features became primary. Which is how women were many times defined: hairstyles, bust size, wasp waists and turn of the leg often seemed to come first.

Which is why the red threads of our Evidence Board will be avoiding super-heroines, for the most part. There are so many, and despite the positive examples (sorry, Mary Marvel and Supergirl), they quickly start to become more about their hemlines and skimpy outfits. Wonder Woman barely solved mysteries or fought conventional crimes, per se, and analysis of the character’s history starts shading us into the territory of her creator’s personal fetishes, which is outside the scope of this series. The same goes for the rough-and-tumble jungle adventure characters like Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, Princess Pantha, Jann of the Jungle or even the relatively chaste and desexualized Nyoka the Jungle Girl. Not enough crime or mystery for all the fur bikinis and cheesecake. At least the gun molls and femme fatales have some timely societal and historical context.

But given this from the start, some of the medium’s early heroines and female protagonists -while still shown to be beautiful- were more than just a collection of extremely capable glamour-pusses. They were smart, tough, self-empowered, canny, independent and seldom folded under pressure. And the industry’s standout female creators tended to be much the same…plus talented writers and artists, to boot.

So, to begin, here’s the one part where super-heroines come in.

While comic books had been around for a few years, either re-printing or mimicking newspaper comic strips, there’s no denying that the medium exploded in popularity (and expanded into a true industry) because of the superhero. Most give credit for originating the idea to Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster’s Superman in 1938 and its first appearance in Action Comics #1. While it’s true Superman popularized the concept, in fact the very first super human in comics was a woman.

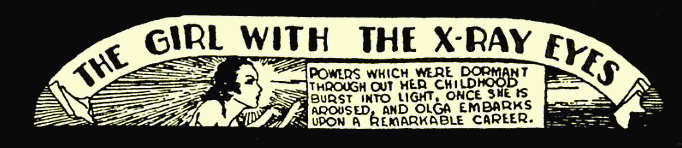

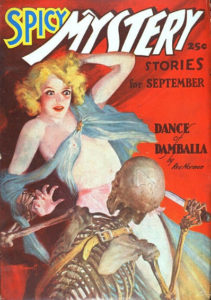

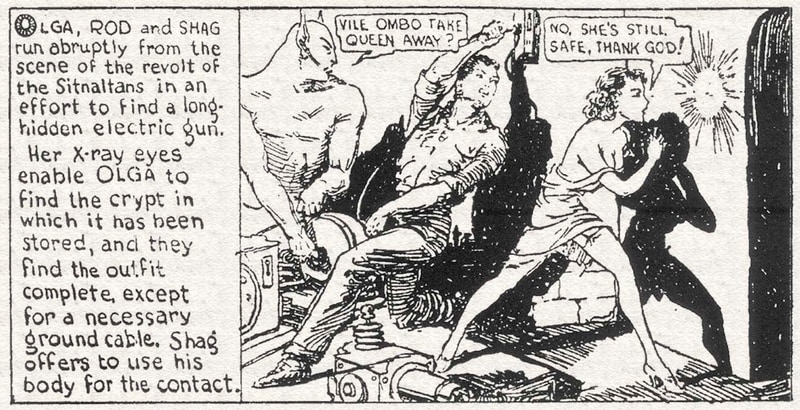

The Astounding Adventures of Olga Mesmer, the Girl with the X-Ray Eyes was produced the year before, by our old friend Al Barreaux and his Majestic Studios, as a sci-fi comic for the September 1937 issue of the pulp magazine Spicy Mystery, a full 10 months before the Man of Steel from the planet Krypton ever appeared. Made for the mob-adjacent publisher Harry Donenfeld, who himself would go on to own both Superman and it’s publishing company DC with his partner Jack Liebowitz, Olga Mesmer (like most Majestic Studios comics for Donenfeld’s “Spicy” line of magazines) would spend a lot of time losing her clothes as she flexed her superstrength and penetrating vision.

The “Spicy” titles were considered equivalent to pornography in their day, and often hounded by legal woes and sold at newsstands “under the counter” in plain, brown paper bags. Olga’s adventures would be short-lived and, ironically, at the conclusion of her series she would bestow a portion of her powers onto her male sidekick (via blood transfusion) so the two could fend off an intergalactic invasion.

The “super” concept immediately made the jump into less salacious and more mainstream publications (as did its publisher, Harry Donenfeld). Superman added the classic vigilante-mystery man trope of the secret identity, and voila! All the dramatic fantasy-projection elements came together, and would prove such a hit that soon the character would expand from Action Comics into his own self-titled series and beyond, selling a million copies a month, touching-off a comic book publishing revolution and jump-starting an entire industry.

And afterward, did anyone ever give Olga Mesmer a thimble of credit? Or Al Barreaux’s studio, who shepherded her into the world? To be honest, there wasn’t time. There was suddenly too much comic book money to be made.

The bullpen structure of Al’s Majestic Studios would prove influential, becoming the model for the several comic-producing studio agencies, or “shops,” that sprang up over the next few years. These were full of cheaply hired talent, hungry for income and opportunity, ready to create, write, draw, letter and package new characters, entire books or sometimes complete lines of titles for the droves of new comic book publishers with Gold Fever that suddenly appeared. (Also, every old, established publisher looking to expand their share of the market, such as Dell or Street & Smith.) The shops would be the doorway and training ground for many influential names in the field (including such notables as Will Eisner, Jack Kirby, Lou Fine and Jules Feiffer). And though it may not have been immediately apparent to the boys when they opened for business, quite a few of these outfits would come to depend on female talent.

To meet demand, fill pages and find that elusive Next Big Hit, these shops generated not just superheroes in a variety of powers, but a whole host of cowboys and magicians, aviators and global adventurers, humor strips, hardboiled detectives and crusading reporters, aimed at readers of all ages and copied from whatever had worked up to that time in literature, pulps, radio, newspaper strips and the movies. Which also meant that soon quite a few comic books began to showcase leading women characters as well.

Because, it turns out, women had been headlining series, and helping drive the marketplace for quite a while. Especially when it came to solving mysteries, these ladies weren’t around to just look pretty. These were independent, motivated, self-empowered women in comic books. Even before the advent of the costumed superhero, these characters existed to clean up crime. Lady private eyes, policewomen, fearless girl reporters, intrepid lady pilots, brave nurses, deadly female secret agents and spies, sexy and mysterious masked vigilantes. Where did these heroines come from, and when did they start to arrive? Who made them? Who read them? And were they inspirational symbols of liberation, or male fantasy archetypes?

Well, to start, many were both. A few were combinations of several of the above elements. Some were created by men to be sex symbols, shapelier and more attractive versions of their male counterparts. Some were written and drawn by women to show the men how sisters could do it for themselves, plus act smarter and look more glamorous doing it. And although the history of comics seems dominated by the men-folk, the truth of course is that women have been working the same crime and mystery territory since the very beginning of the genre, much less its 20th century transformation onto the funny pages.

As far back as 1841, the exact same year Edgar Allan Poe is credited with creating detective fiction with his story “Murders in the Rue Morgue” and his character C. Auguste Dupin, the first female sleuth arrived. Out to solve the riddle of her brother’s disappearance and the untimely murder of her guardian, she appeared in the British magazine serial Adventures of Susan Hopley; or, Circumstantial Evidence. First published anonymously, but later revealed to be written by woman author Catherine Crowe, the heroine—although only a maid by profession—is an earnest and plucky lass who follows a trail of clues and proves her brother’s innocence of the crime, even after he himself is murdered. In the end, Susan avenges her late sibling and reveals the actual culprits. That she works as a simple domestic makes her no less amateur a detective than Poe’s Dupin—or Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes almost half a century later, for that matter—and maybe even better because of it. Susan Hopley is a step closer to real working-class investigators, not some louche, idle dabbler like her more famous male counterparts. A best seller, Adventures of Susan Hopley was adapted successfully to the London stage in the very same year of its publication, with more reprintings and further adventures to follow.

To Be Continued…