By Dale Berry

MWA NorCal board member Dale Berry is a San Francisco-based writer and illustrator, who has produced independent comics since 1986. His graphic novels (the Tales of the Moonlight Cutter series, The Be-Bop Barbarians with author Gary Phillips) have been published by mainstream, as well as his own imprint, Myriad Publications, and his graphic short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His life has included stints as a carnival barker, Pinkerton’s guard, professional stagehand, fencing instructor, and rock radio DJ. He and Gary Phillips wrote the chapter on Graphic Stories for MWA’s How to Write a Mystery.

Note: click on an image to see a larger version.

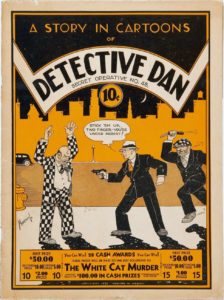

Following an explosion in organized crime, and just in time for the repeal of Prohibition, Detective Dan, Secret Operative No.48, written and drawn by Norman Marsh, was published in April 1933 by the Humor Publishing Company. It was the first single themed, single character comics publication featuring all original art and story, in a 36-pg. tabloid, 10” x 13” with three-color cardboard covers (black, white, and orange) and a cover price of 10 cents, to ever be produced in the US and sold on American newsstands.

In title and visual approach, Norman Marsh—hoping to showcase his creation for sale to the newspaper syndicates—covered all his bets: Detective Dan, packaged like early comic strip reprint books and drawn like Dick Tracy’s Chester Gould, was also a mash-up of both the Dick Tracy and Secret Agent X-9 strips. Dan only lasted a single issue, to be followed by two more one-shots in the same vein from Humor Publishing: Ace King the American Sherlock Holmes and Bob Scully the 2 Fisted Hick Detective.

But after changing the character’s name to Dan Dunn, Marsh would sell his series to Publishers Syndicate, and achieve some success. Breaking into newspapers in September 1933, the Dan Dunn comic strip would run for a decade. It would also have two original pulp magazines in 1936, a radio show running for fifty-seven episodes in 1937, seven Big Little Books from 1934-1941, merchandising, and be reprinted as a supporting feature in various comic books by Eastern Color, Dell, and Western Publishing until 1944.

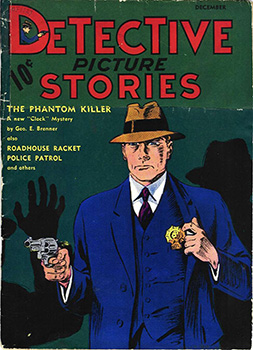

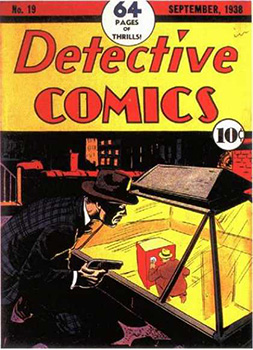

Marsh’s indie presentation booklet for Detective Dan would become, over time, the standard format for both original, single-themed comics publications and the omnibus reprint titles. In short, comic books as we’d recognize them today. Following on its crude heels came the likes of Detective Picture Stories (Centaur Publications, December 1936), Western Picture Stories (Centaur, February 1937), and Detective Comics (National Allied Periodicals, March 1937).

No longer dependent solely on newspaper syndicates, several publishers—some large and corporate owned, some smaller and independent—had begun generating their own comic-filled books. Many were already producing pulp magazines and brought those sensibilities and genres with them when they began creating content in the new medium.

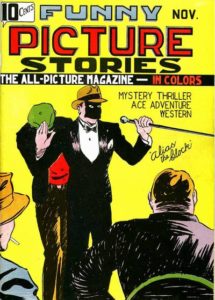

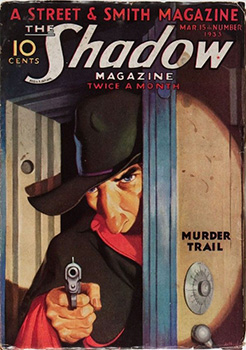

One, called Funny Picture Stories (Centaur, November 1936 and featuring a variety of genres), showcased on its debut cover the first masked mystery man in comic books, a dangerous vigilante-sleuth called The Clock. In 1938, Detective Comics would follow suit with a costumed crimefighter called The Crimson Avenger. These two were heavily influenced, not only by hardboiled crime fiction, but also by a growing tide of mystery men on radio and in the pulps, such as The Shadow and The Green Hornet.

But, why all the masks? Discussing the “Avenger/Artful Dodger” concept in literature, Josh Glenn, author, semiotician and columnist for the Boston Globe, attributes its origin as reflecting “[…] a counter-Enlightenment phenomenon, one which first appeared in the form of 18th century gothic melodramas full of curses, disguises, treasure, mysterious codes. Modern society’s constitutional law is corrupt and slow; as a result, evil (usually in the form of injustice and oppression; a system that refuses to take account of human needs) too often goes unpunished, hence the hope that a fiercer and purer authority will arise to punish evil on behalf of evil’s victims.” The idea of a liberator beyond the law with a secret identity emerges from these classic mystery genre elements.

This is where the threads on our Evidence Board really begin to lead somewhere. From its deep roots in crime and detective fiction, reflecting a time of great social uncertainty, the fledgling medium of comic books evolves something new: the superhero.

Essentially, the new mystery men of the 1930s were extensions of the well-established trope of the ‘good guy’ cowboy, the Western gunslinger in white hat who defends the innocent homesteaders with his lightning-fast draw. (And in fact, the origin story for the Green Hornet revealed he was the direct nephew of the Lone Ranger, both characters having been created by the same man, author George W. Trendle.) Transported to the modern era and dealing with a harsher, mechanized reality, these archetypes had themselves become darker and scarier, exchanging their horses for armored vehicles, ten-gallon hats for fedoras, and their six-shooters for .45 automatics and other specialized weaponry. Forged on radio, they would soon cross over to print and screen, and there evolve further.

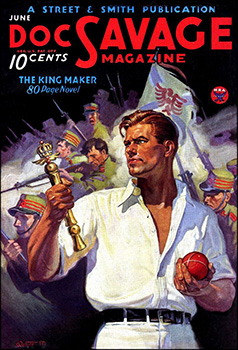

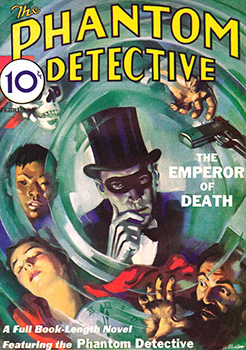

Developing during the anxious years of the Depression, and no-doubt directly related to its effect, were two unique pulp magazine offshoots of hardboiled and mystery fiction: the sub-genres known as Hero Pulps, and its polar opposite, Weird Menace. Hero Pulps offered a range of either dangerous mystery-men vigilantes, or righteous defenders of high moral character, solving problems and battling crime at home and around the world.

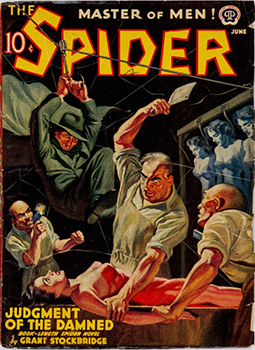

Each bore a specific trademark, name, gimmick, motif, or colorful costume to identify them, and to reinforce their image as beings of superior mind and physical prowess standing against the forces of evil. The Shadow, Doc Savage, The Spider, The Phantom Detective, The Avenger, and The Black Bat were all popular examples of this genre, and confronted everything from small-time crooks, insurance fraud, and locked-room murder mysteries to terrorist threats and global conspiracy, with zombies, dinosaurs, mad science or lost civilizations thrown in for good measure. Many went on to be featured in radio shows, movies, and comics for years outside of their pulp existence.

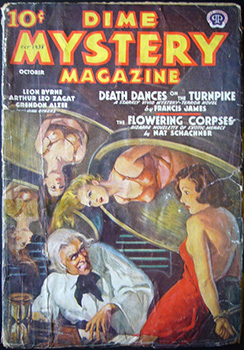

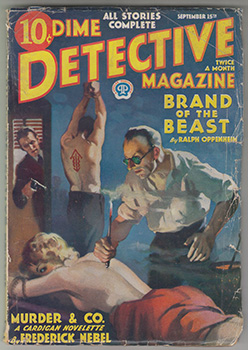

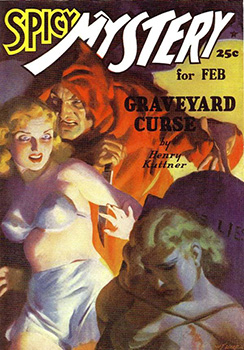

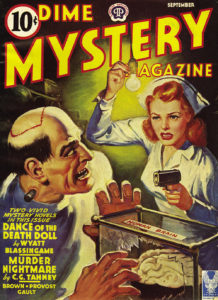

Weird Menace pulps showcased stories fusing crime and horror with sex, with a specific focus on sadistic murder methods, psychological aberration, and strange, hidden, pathological motives. Flirting with, but stopping just short of the out-and-out supernatural, each story would reveal a solution (or, at least, a semi-reasonable “explanation”) for its baffling mystery at the end. Featuring lurid sexual violence and bloody carnage, the Weird Menace pulps were clear forerunners to today’s “serial killer” stories and sensationalized case-studies, with much focus on deviance, deformity, and increasingly, torture.

Also known as ‘Shudder Pulps,’ typical titles were Strange Detective Stories, Dime Mystery Magazine, Dime Detective Magazine, Terror Tales, Horror Stories, Startling Stories, and Thrilling Mystery. Here the cops, P.I.’s or unlucky civilian investigators would tackle lunatic murderers or rapist mad scientists or discover the reading of the family will at the old mansion might also include a hooded, orgiastic blood-sacrifice cult in the basement, with beautiful, violated victims tied naked to an altar in need of rescue.

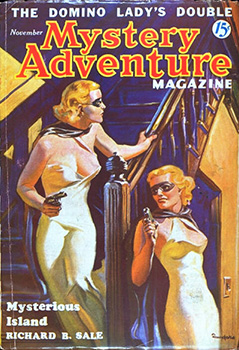

A few characters bridged both genres. The Domino Lady was a series found in the pages of Saucy Romantic Adventure and Mystery Adventure Magazine in 1936. After her DA father is murdered, Ellen Patrick, a UC Berkeley educated socialite, dons a mask and backless dress to avenge him and fight crime. With a syringe of knockout serum, a .45 automatic and sheer glamour, she steals from criminals and donates the proceeds to charity (after taking her cut), leaving behind a distinctive calling card and a trail of dishabille.

More reactionary was The Spider, Master of Men, star of his own magazine, who donned fangs and a fright-wig to slay fiendish masterminds that tortured and slaughtered multitudes every issue. (Minor examples: unleashing pigeons with bubonic plague onto Manhattan, until wagons rolled through the city streets collecting the hundreds of dead; poisoning children’s milk supply on the entire Eastern seaboard; wrecking subways and skyscrapers to enable a terrorist plot to conquer America. You know, small time stuff.) Masochistic, extreme, and perhaps a little crazy himself, the character would combat wholesale, apocalyptic destruction on a monthly basis throughout the 1930s and 40s, and even inspire two movie serials.

One person who seemed at home with either world was crime writer Robert Leslie Bellem. He worked in Los Angeles as a newspaper reporter, radio announcer, and sometime film extra, but after breaking into the market in the 1920s with a short story in Argosy, Bellum would eventually settle into a comfortable niche writing for both Hero Pulps and Weird Menace. With a breezy, self-mocking style that both sensationalized and satirized his hardboiled material (Bellum is famous for creating the oft-quoted line, “My roscoe yammered ‘Ka-chow!’”), he worked under multiple pseudonyms as well as his own byline, also partnering with other writers, and all while cranking out many stories for many titles throughout the 30s and 40s. Bellum, too, would also dip his hand in comics, films and, after the demise of the pulps in the 1950s, television, where he wrote for Perry Mason, 77 Sunset Strip, and many others. His final fiction output is reckoned to have been around 3000 stories.

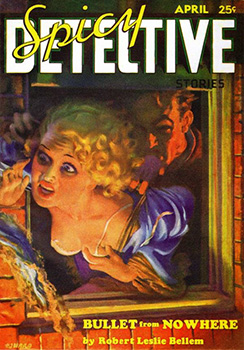

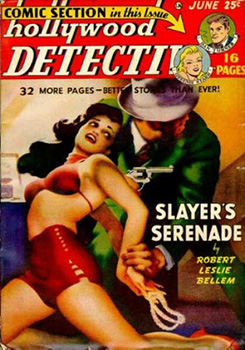

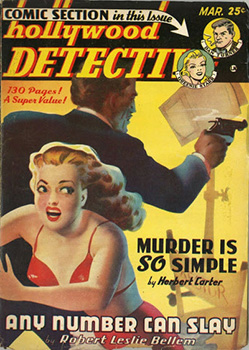

For the Hero Pulps, he churned out the daredevil adventures of Jim Anthony, Super-Detective, star of his own magazine, a crime buster who could see in the dark. In the Weird Menace category, Bellum made his home at the Spicy magazine line, in titles such as Spicy Adventure, Spicy Mystery and Spicy Detective (terms like “Saucy” and “Spicy,” in this context, meant stories with more nudity and sexual content than other mainstream magazines, and were often sold at newsstands ‘under the table’). There, for nearly two violent decades, his creation Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective would shoot and wisecrack his way through Tinseltown, dividing his time between solving crime amongst studios, movie stars, and the underworld.

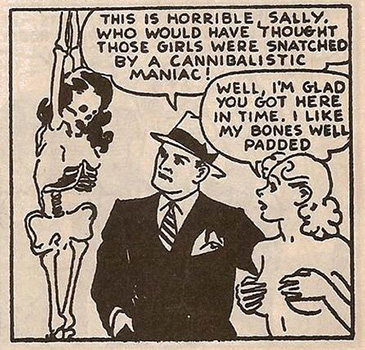

By the late 1930s, in addition to its residency with Spicy Detective, the Dan Turner character would prove popular enough to graduate into his own self-titled Hollywood Detective pulp magazine, with several stories per issue and the unique, cross-over gimmick of short comic stories (!) as filler. A cursory glance at these comics, also written by Bellum and drawn (crudely) by pulp artist Adolphe Barreaux, show that however traditionally hardboiled the basic premise, the character never strayed far from his Weird Menace, exploitation roots.

With less sleaze, but just as weird, this same type of “hardboiled horror mystery” hybrid had crept up through the Depression and into radio thrillers, “B” movies, and newspaper comic strips. Thus, in the funnies, Dick Tracy would shoot it out with grotesque crooks called Flattop, Prune Face and the Mole, while on the air, The Shadow would rescue Margo Lane from brain-transplant with a gorilla by a crazed, cackling surgeon in a sanitarium. Mystery, crime, and horror began to be conflated.

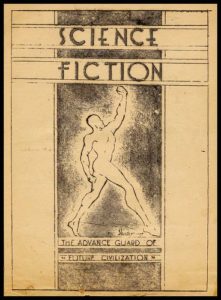

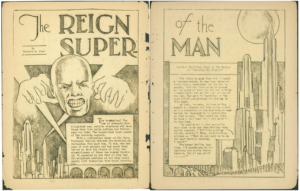

But meanwhile, good ol’ Detective Dan (remember him?) would also have one more, lasting impact: he’d become a direct influence on two teenagers from Cleveland, OH named Jerry Siegel and Jerome Shuster. Inspired by Marsh’s first booklet, these early fans turned a villainous, world-conquering character they had created for their mimeographed fanzine, Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization (April 1933), into a heroic adventurer, then redrew him as a comic strip. After an ‘encouraging meeting’ with Marsh, who’d travelled to Cleveland to sell his character to a newspaper syndicate, the two believed they’d sold their revamped character, now called The Superman, to Humor Publishing Co., with hopes that they, too, would soon be in the newspapers.

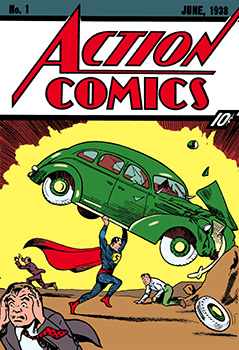

Although Marsh would ultimately pass on Siegel and Shutter’s creation, as would every other comics publisher for the next five years, the character, further revamped, and now sporting a cape and colorful costume, was eventually sold for $130 to National Allied Periodicals. Now just called Superman, he would finally debut in National’s Action Comics #1 (June 1938), to become the first “superhero” in the history of comics, a major bestseller and a global icon.

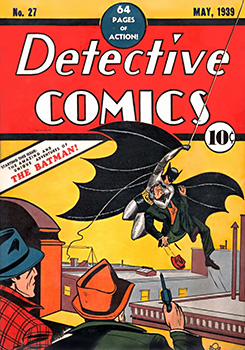

That next year, spurred by this success, National Periodicals introduced The Batman into the pages of their Detective Comics (issue #27, March 1939). Created by Bob Kane, his assistant Jerry Robinson, and his ghost-writer Bill Finger, The Batman was a menacing costumed mystery man who fought weird criminals and was drawn in the violent, Dick Tracy mold. National Allied Periodicals, which would soon change its name to DC (for Detective Comics)-National, later just DC, had found another hit.

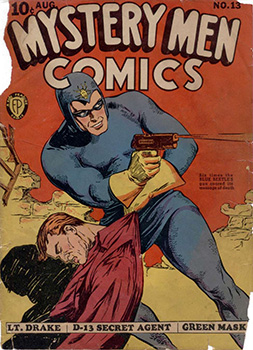

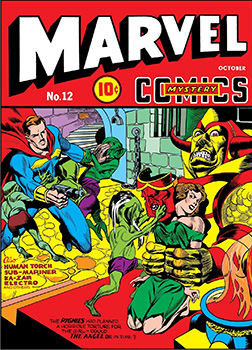

With the advent of these two new crimefighters, light and dark, new floodgates would open, and as the decade turned, a legion of costumed, gimmicked heroes and heroines would pour forth from every corner of the publishing world: The Blue Beetle, The Masked Marvel, Wonder Man, The Flame, Wonder Woman, The Flash, Miss Masque, The Shield, Captain Marvel, Captain America, Mary Marvel, Doctor Fate, The Human Torch, The Black Hood, The Spirit, Miss Fury, Lady Luck.

Each one contended against every conceivable form of evil, from political corruption to everyday street crime, from supernatural horror to galactic invasion. They’d also help expand and introduce the comic book, and its format, genres and tropes, to publishers across the globe. And when World War II finally broke out, they stood ready to represent America, and fictionally defend the nation from the onslaught of the Axis menace and beyond.

So, with the coming of this new type of book and its new type of character, social forces and sub-genres merged. Pulpy heroes battling weird menaces, whether super-powered or just dressed that way, through ebb and flow, are still with us today, and across all media platforms. And at their root, all are derived from and influenced by mystery melodramas, hardboiled crime, and detective fiction. The very cops and P.I.’s they were created from were suddenly relegated to the status of back-up features and supporting players.

That is, until 1942, when True Crime entered the funny books.

To Be Continued…

(Credits: All images and samples are used for educational purposes only. Action Comics, Detective Comics, Superman, and Batman are copyright DC Entertainment, Warner Bros. Global Brands and Franchises division of Warner Bros., and AT&T’s Warner Media, respectively. Marvel Mystery Comics and its related characters are copyright Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Worldwide Inc., a division of The Walt Disney Company. The Shadow and Doc Savage are copyright Conde-Nast. All others are public domain, and/or copyright all respective creators.)